Just over a hundred years ago, an American archaeologist discovered a series of spectacular tomb paintings dating from about 200 B.C.E. at a site in the foothills of the Judean mountains. Yet, within a few years, these precious works of art had faded into oblivion, and since then they have been known to the world only through a set of inaccurate colored lithographs, first published in 1905.

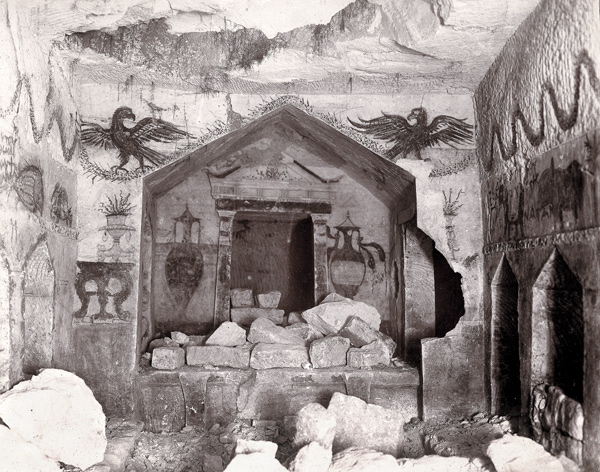

Fortunately, the first scholars to see the paintings had the foresight to have them photographed immediately, but for years these valuable plates lay undisturbed in the archives of the Palestine Exploration Fund in London. Now, the readers of BAR can share my wonder and delight in seeing these long unseen treasures.

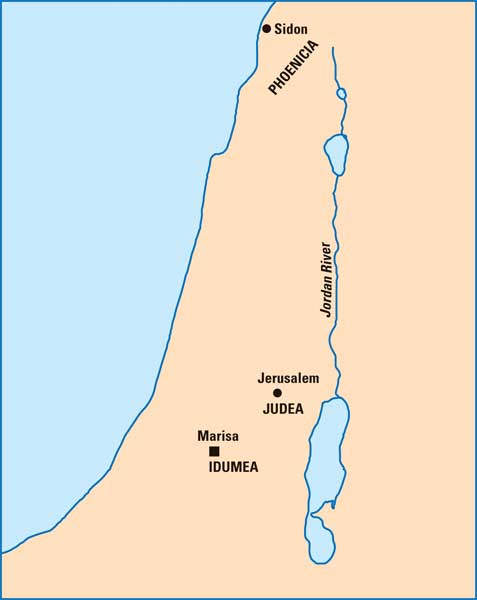

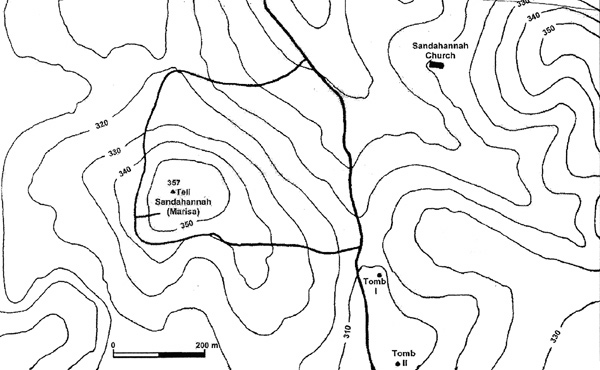

Our story begins in the summer of 1900. Frederick J. Bliss, an archaeologist who had received his training from William F. Flinders Petrie in Egypt, and his Anglo-Irish deputy, R.A. Stewart Macalister, conducted a three-month campaign of excavations at a mound called Tell Sandahannah, one mile south of Beit Guvrin (Beit Jibrin) and less than 40 miles by road southwest of Jerusalem.1 Tell Sandahannah is identified with Biblical Maresha, called Marisa in the Hellenistic period.

The excavation at Tell Sandahannah was the last in a series at four sites in the Shephelah (the gently rolling hilly area between Israel’s coastal plain and the Judean mountains) sponsored by the London-based Palestine Exploration Fund (PEF).2 The primary focus of the excavations was Tell as-Safi (Tel Tsafit), which was then, and is once again, considered to have been the site of Biblical Gath, home of the Philistine giant Goliath.a

Bliss and Macalister laid bare the two upper strata at Tell Sandahannah, which dated to the Hellenistic period.3 At that time the town was protected by strong walls and had an almost rectilinear grid of paved streets, buildings and an impressive drainage system; the many rich finds unearthed by Bliss and Macalister attested to the town’s importance at that time. The many examples of Hellenistic pottery included 328 stamped Rhodian amphora handles, bearing dates from the beginning of the third to the end of the second century B.C.E. Other imported wares included Megarian ceramic bowls, which have distinctive molded decoration and were thought to have been produced at Megara in Greece during the Hellenistic period. The base of a large sculpture of an eagle contains a dedication to Apollo by “the son of Kraton,” and another inscription on a statue base bears a dedication to Arsinoë II, the wife of Ptolemy IV Philopator (221–203 B.C.E.). This picture of a prosperous Hellenistic town is reinforced by the large number of subterranean cisterns, burial chambers and other installations in and around Tell Sandahannah from this period.b

The area had long been notorious for its tomb robbers; the excavations at Tell Sandahannah, however, gave the treasure hunters fresh encouragement. In early June 1902, the American scholar and Episcopal minister John Peters and the German classical scholar Hermann Thiersch were alerted to the haphazard discoveries being turned up in these illicit excavations. While touring the area, their Nubian guide alerted them to two burial caves (called by them Tomb I and Tomb II) that had recently been discovered by the tomb robbers. The guide told them the tombs contained paintings. What they found when they entered the burial caves exceeded their wildest expectations: The walls were decorated with brightly colored figurative paintings from the Hellenistic period—the same period to which the excavated strata on the tell belonged. Unfortunately, by the time Peters and Thiersch had arrived on the scene, the faces of the painted human figures had been effaced by pious Muslims from the nearby Arab village. Islam has a strong tradition against depictions of humans, and the villagers found the human portraits in the burial caves offensive.

To make matters worse, looters had by then carted off most of the contents of the tombs to the antiquities market in Jerusalem, and only a few items remained for the scholars to examine and publish.

On that first visit, however, Peters and Thiersch spent a full day taking measurements, making sketches and copying inscriptions. The following week, they returned with Chalil Raad, one of the leading commercial photographers in Jerusalem. He made a series of 10-by-12-inch photographic plates of the tomb paintings. Peters and Thiersch described the challenges faced by Raad:

The work of photography was peculiarly difficult, owing to the lack of light and ventilation: there was no air to dissipate the smoke produced by the magnesium with which the flashlight was made, and after one or two photographs had been taken, the air would become so thick that nothing further could be done for many hours. This was only one of many serious difficulties which Mr. Raad encountered. Fortunately there was no question of night or day in the tombs, and photographs could be taken or inscriptions copied at one time as well as another.4

Peters and Thiersch showed their photographs and copies of the tomb inscriptions to Dominican scholars at the Monastery of St. Stephen and the Ecole Biblique in Jerusalem. Three of them, Father Marie-Joseph Lagrange (the founder of the monastery and the associated school), Father Louis-Hugues Vincent and Father Antoine Raphael Savignac (three of the most prominent scholars of their day), visited the tombs and made their own sketches, watercolor paintings and records of the inscriptions.

From Jerusalem, Peters wrote to Charles Wilson, the chairman of the PEF who had led the Ordnance Survey of Jerusalem (1864–1865), stating that he and Thiersch had prepared the draft of a study of the Marisa tomb paintings, including photographs, plans and squeezes of incised inscriptions (a squeeze is an impression of a relief feature made on wet paper that is pressed against it). He offered this material to the PEF if it were willing to publish their work as a monograph and “repair the holes made in our pockets by our too great enthusiasm in the interest of science,” that is, to reimburse them for their costs (mostly Raad’s fees). The PEF Committee accepted Peters’s proposal on October 7, 1902, and, after the manuscript was received, sent Peters a check for £40.

Unfortunately, in 1902 the photographs could only be taken in black and white. At Peters’s request, the PEF agreed to publish most of the pictures of the paintings in color. The color sketches and architectural drawings of the tombs that had been made by Fathers Vincent and Savignac were lent to the PEF to assist in the preparation of color lithographs for the publication. However, fanciful restorations made in the French watercolors were also reproduced in the published illustrations, despite Father Lagrange’s own dissatisfaction with the sketches and his recommendation that the PEF stay faithful to the photos. (One of the fanciful restorations appeared on the cover of the January/February 1982 issue of BAR.)

When Thiersch saw the proofs of the color plates, with their overdrawn features and strong coloring, he was dissatisfied and asked Wilson to include all the black-and-white photographs of the paintings in the publication. His request was turned down because of expense. The PEF publication appeared in early 1905, under the title Painted Tombs in the Necropolis of Marissa (Marêshah).5 And that is what the world has known of these paintings since 1905.

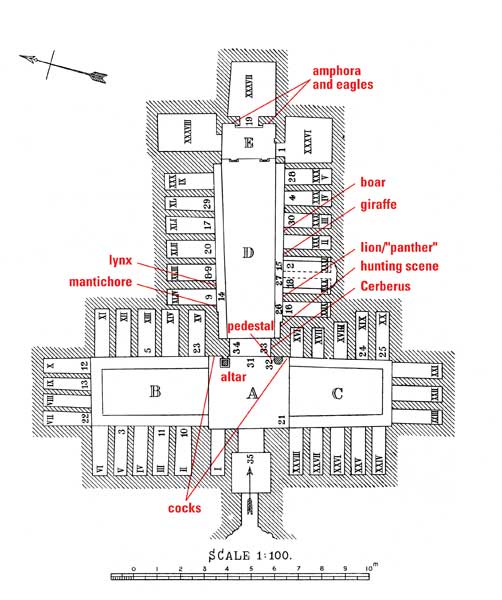

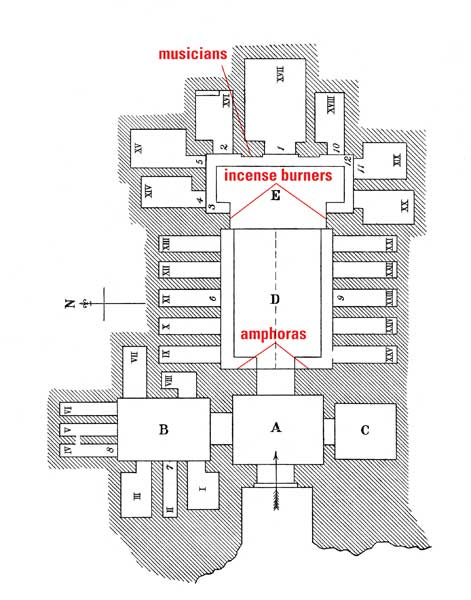

The two painted tombs are about a half mile southeast of Tell Sandahannah. Tomb I, measuring 57 by 72 feet, is the larger of the two and is the more richly decorated (see plan). It contains 41 deep burial recesses, or loculi. Benches project below the loculi and run along the length of the north and south walls. On the right side of the entrance to the middle burial chamber a statue stood originally on a pedestal cut out of the rock. On the other flank is a square altar, also hewn from the rock. Peters and Thiersch found both features smashed. Several of the tomb chambers have flat roofs, others have barrel-shaped ceilings, and all the burial recesses have triangular gables. These burial caves owe their stylistic features to the tombs of Alexandria from the late fourth to the early second century B.C.E., a point to which I will return later.6

Some 35 inscriptions, carved and painted and all in Greek, were found in this tomb. One inscription, an epitaph inscribed above a doorway in the eastern recess, is particularly important because it mentions Marisa and the presence of the Mediterranean trading community established there that was responsible for the tomb. It reads, “Apollophanes, son of Sesmaios, head of the Sidonians [that is, the Sidonian community or, possibly, colony] at Marisê thirty-three years, reputed the best and most kin-loving of all those of his time; he died, having lived seventy-four years.”7 Sadly, some time later, this inscription was cut out and removed by robbers.

The eastern end of the central chamber (marked E on plan) is recessed, with a doorway in the center, modeled like a temple shrine, with flanking pilasters and covered by a Doric frieze and triangular gable. In front of the recess is a high ledge sculpted to resemble a funeral couch, a feature also found in Alexandria and other Hellenistic sites. The recess serves as an inner vestibule, serving three small tomb chambers.8

Tall amphoras with lids and streaming ribbons, or fillets, flank the ornamental doorway of the eastern recess. The Greeks commonly used large amphoras as containers for wine; these vessels in Tomb I may be indications of the cult of Dionysus, the god of wine. On either side of the eastern recess were representations of large eagles with outstretched wings standing on a wreath that snakes its way along the length of the tomb. Below each eagle is a golden tripod table supporting an incense burner. Each is of a different design, and one has a base decorated with griffins.

The main chamber (D) of Tomb I is highly ornamented and imitates a freestanding building.9 The overall effect of the decoration in the chamber is that of a luxurious reception hall. The sculpted couch at the eastern end of the chamber, together with the stone benches running down the long sides, strengthens its relationship with a dining hall. The three-sided arrangement of the couch and the two long benches on either side corresponds with Greek and Roman banqueting practice. Here it may recall a funeral banquet, a practice well-attested in Alexandria, Petra and elsewhere. (This three-sided arrangement gave its name to the Roman word for dining room, triclinium, literally three couches.)

At the entrance to the main tomb chamber, a pair of cocks straddles the doorway leading into the chamber, and the three-headed dog of the underworld, Cerberus, is painted on the right-hand doorjamb. The roosters are shown strutting away from the doorway, with their heads turned back towards the entrance; they are vigorously painted in bold strokes of black paint. The artist seems to have taken delight in painting these birds in three-quarter view. The wreath with streamers, which appears to hang from the base, is actually by a later hand.

The Cerberus in the doorway is portrayed in profile; one of its three heads is facing the tomb chamber and the other two are pointing back; a front foot is raised, suggesting forward movement. The beast is painted in thick black lines, similar to the cocks, but its silhouette is given added emphasis by the vigorous hatching scored into the white-hued rock surface. The black collar worn around each neck of Cerberus suggests domesticity, although the clawed feet indicate something more sinister; the white hatching around the animal, revealed in the original photograph, gives it an eerie glow. Both the cock and Cerberus have associations with death and the afterlife: In Greek tradition, the cock was seen as the protector of souls on their journey to the underworld and also in Hades, and Cerberus is extensively represented in classical art and literature.

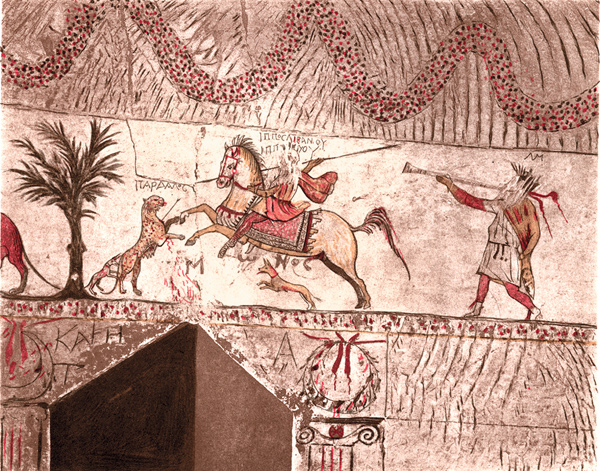

Inside Tomb I, we get to what is undoubtedly the most remarkable of the paintings in the Marisa tombs—a long frieze above the burial niches in the long walls of the main chamber (D) that depicts a series of wild animals, preceded by a leopard hunt. Facing south and going counterclockwise, the cycle begins with the hunting scene. At center a hunter mounted on horseback is depicted in the act of hurling a spear at a leopard. The white horse, which rears up before the wild beast, has an ornately decorated saddlecloth. A hunting dog accompanies the rider and runs alongside him. An attendant behind the rider is shown blowing a long trumpet; he holds the trumpet in his right hand and balances himself by placing his left hand against his hip. The spotted leopard is bleeding from a wound caused by an arrow, which remains lodged in its breast. A second hunting dog pins down the leopard from the rear. Above the horseman a Greek inscription written in black paint reads, “the white horse of the rider,” and above the leopard is the caption pardalos, a variant of the usual Greek word for leopard, pardalis. The Arabian leopard (Panthera pardus nimr) is indigenous to the Levant. Now rare in the Holy Land, specimens are occasionally seen near the Dead Sea.

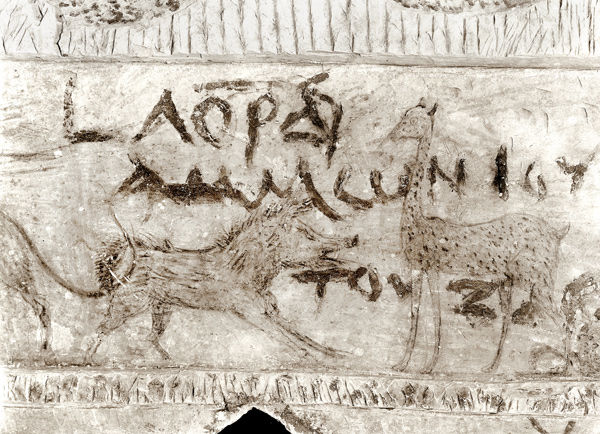

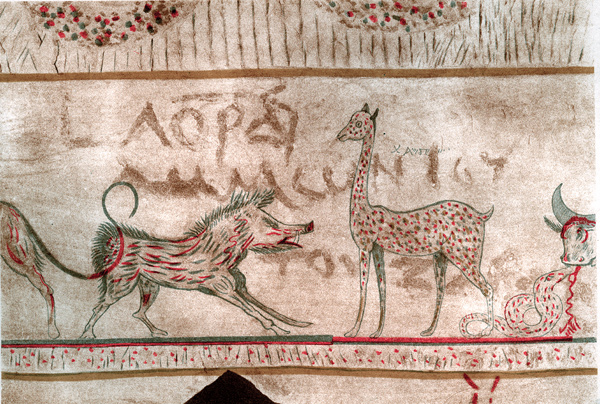

A tree resembling a palm divides the hunting scene from the rest of the frieze, which shows a sequence of wild animals, many labeled with captions in Greek. The first of these beasts is a maned lion , but its caption, pantheros, is puzzling, because the term “panther” was generally applied to spotted felines. Further to the left, after a break, a huge bull is shown collapsed on bent forelegs, with blood running from its mouth and a large snake.

Behind the bull are a giraffe facing a boar . To the left, is a winged griffin with a lion’s body and eagle’s head. In antiquity, the griffin was believed to exist in eastern lands, in India or central Asia.10 Next comes a running horned oryx, identified by its caption (and by its striped body). After another tree divider, a two-horned African rhinoceros appears, again confirmed by a caption. Finally, there is a war elephant equipped with a saddle; it is led by an African, labelled “Aethiopia,” but he is largely obliterated.11

On the opposite side of the chamber are two fish, one with the trunk and tusks of an elephant and the other with the head of a rhinoceros, apparently mimicking the animals opposite. Left of them is a crocodile with an ibis perched on its back and a hippopotamus behind. This scene clearly depicts the natural life of the Nile River. Next are a wild ass struggling with a snake, two unidentified animals, one with a horn on its snout, and then a porcupine, bristling with quills. Standing with its back to the porcupine is a lynx , looking quite comical with its large eyes, elongated ears sprouting large tufts of hair and a ruff of hair on its throat. At the end of the frieze stands a feline creature with a human face and beard. I have identified this image as the mythical mantichore or martichore, described by ancient Greek authors as a fearsome beast native to India; the name means “maneater” in Old Persian.

Tomb II, just south of Tomb I, is similar in type but smaller in size. It contains 25 burial niches and 12 inscriptions. Above the burial niches are painted garlands, and among them, round wreaths. Large amphoras, similar to those in Tomb I, are painted on either side of the entrance to the central hall. Tall incense burners appear on the pilasters between the central hall and the hall behind it. There are two small human figures at their base. Near one of the internal doorways is a musician scene; it shows a man clad in a short tunic and with a wreath on his head, followed by a woman wearing a long, multicolored Greek-style dress (called a peplos) and playing a portable harp. The actual appearance of this painting as seen by Peters and Thiersch is shown in the black-and-white photographs, but the faces and other details are shown in the imaginatively restored colored lithograph.

Why did the artists of Marisa decorate Tomb I with wild animals and with a hunting scene? Hunting scenes appear frequently in funerary contexts in the classical world12 and were particularly popular on tombs and sarcophagi of aristocrats because they projected an image of bravery.13 Wild animals appear widely in artistic and architectural decoration of the Hellenistic period, especially in Hellenistic Alexandria.

A close parallel to the Marisa frieze is the Stag Hunt Mosaic from the Shatby district of Alexandria, now in the Graeco-Roman Museum in that city.14 It takes its name from the figurative scene in the central panel, showing a stag hunt. The border of the mosaic is decorated with animals15: a stag, a gazelle, a hyena, a bull, two wild boars, griffins, leopards, lions and lynxes.16 The similarities between this mosaic and the Marisa animal frieze are striking. Not only are several of the animals of the same species, but they both depict animals and do not include a detailed landscape setting (other than an indication of the ground surface and occasional trees). The ordering of the animals is also very similar: They are not all grouped into facing pairs; rather, some follow behind their neighbors. They are mostly shown in profile, although a few of the animals turn their heads toward the viewer. The Shatby mosaic has been dated by the Polish scholar Wiktor Daszewski to the first quarter of the third century B.C.E., largely on stylistic grounds. The fact that the find spot of the Shatby mosaic was in the palace area of Alexandria suggests that the roots of the Marisa paintings are to be found in the art of the Ptolemaic court.

The wall paintings at Marisa include animals specific to the Nile Valley and the interior of Africa—the hippopotamus, giraffe, crocodile, ibis, African elephant and African rhinoceros—but they also include the leopard, lion, boar and lynx, which were native to Israel in antiquity, and also two mythical beasts, the griffin and mantichore, which were believed to inhabit Central Asia and India. The interest in African animals may be linked to the opening up of trade with the Horn of Africa by Ptolemy II and his two immediate successors, largely for the purpose of importing elephants for their armies.17 The elephants employed by Hellenistic armies were the equivalent of today’s armored vehicles. Their deployment by Seleucid armies is succinctly described in 1 Maccabees 6:35–37:

The great beasts were distributed among the phalanxes; by each were stationed a thousand men, equipped with coats of chain-mail and bronze helmets. Five hundred picked horsemen were also assigned to each animal. Wherever it went, they went with it, never leaving it. Each animal had a strong wooden turret fastened on its back with a special harness, by way of protection, and carried four fighting men as well as an Indian driver.

In the great carve-up of Alexander the Great’s empire after his death in 323 B.C.E., the Seleucids, based in Syria, gained the territories bordering on India and control of the supply of Indian elephants. Their main rivals, the Ptolemies, based in Egypt, were forced to look elsewhere for their war elephants; this led them to expand along the Red Sea coast of Africa and to an organized trade in animals from the Horn of Africa.18 Ptolemy II appears to have kept a zoo that contained many species.19 An assortment of wild animals, including lions, leopards, lynxes, giraffes, elephants, oryxes, wild asses and an African rhinoceros, were paraded in a procession of Ptolemy II Philadelphus in Alexandria, as part of a pageant on the theme of the Greek god Dionysus and his cult.20

Another element in the Dionysiac tableaux in that procession, the giant golden amphoras raised on golden tripod tables, is also relevant to the Marisa paintings.21 The cult of Dionysus was promoted by the Ptolemaic dynasty from its beginning.22 Ptolemy IV Philopator, who held sway over Marisa toward the end of the third century B.C.E., was a devotee of Dionysus, for which he received the epithet “youthful Dionysus.”23 The cult of Dionysus was widely encouraged in the Ptolemaic kingdom during his reign.24

According to Greek myth, Dionysus was associated with the netherworld, and he offered his followers a happier time in the afterlife. Classical tradition frequently refers to Dionysus visiting or even dwelling in the world of the dead. For this reason, Roman sarcophagi are frequently decorated with Dionysiac scenes. One of the odes of the Roman poet Horace closes with the picture of Cerberus, peacefully greeting Dionysus as he enters the underworld, “brushing him fondly with his tail,” and this three-headed watchdog “touched his [Dionysus’s] legs and feet with his triple tongue” as the god of wine departed.25 The Cerberus and the cocks painted at the entrance to the main chamber of Tomb I would suggest that the paintings were intended to reflect on death and the afterlife.

The subjects depicted in the Marisa wall paintings, especially the animals of the Nile, and their Dionysiac imagery point to the late third century B.C.E. as the time when they were created. The dedication to Arsinoë III, the wife and sister of Ptolemy IV, discovered in the Hellenistic town of Marisa and mentioned earlier, reminds us of the links between Marisa and this monarch.

The paintings in Tombs I and II at Marisa constitute a unique document of provincial art and culture from Ptolemaic times, and the timely republication of the original photographs will allow a fuller appreciation of these marvels of Hellenistic art.26 These tomb paintings graphically illustrate the extent to which Hellenization had taken hold on a community close to Jerusalem. Only a few decades later that process would be ruptured: the Maccabean rebellion would spearhead a Jewish reaction against Hellenic customs and institutions.27 That rebellion is still celebrated by Jews in the festival of Hanukah. But in the end the floodtide of Hellenism could not be resisted, neither in Idumea nor in Judah.

MLA Citation

Footnotes

See Aren M. Maeir and Carl S. Ehrlich, “Excavating Philistine Gath,” BAR, November/December 2001.

For more on this fascinating site, especially its extensive underground structures, see Amos Kloner, “Underground Metropolis—The Subterranean World of Maresha,” BAR, March/April 1997.

Endnotes

Frederick Jones Bliss (1859–1957) was the son of Dr. Daniel Bliss, the founder of what is today the American University of Beirut. Bliss had carried out excavations with Archibald C. Dickie, tracing the ancient walls of Jerusalem (1894–97), prior to his work with Macalister in the Shephelah. Robert Alexander Stewart Macalister (1870–1951) hailed from an Anglo-Irish family. His father, Alexander Macalister, was a distinguished professor of anatomy at Cambridge. Following the expedition to the Shephelah, Macalister conducted excavations at Gezer for the Palestine Exploration Fund in 1902–1905 and 1907–1909. He was subsequently criticised for the poor methodology of these excavations. In 1909 Macalister was appointed professor of Celtic archaeology in Dublin.

Frederick J. Bliss and R.A. Stewart Macalister, Excavations in Palestine during the Years 1898–1900 (London: 1902).

Bliss and Macalister Excavations in Palestine, pp. 52–70, 107, 124–134, 154–187, 200, 209, 238–254; M. Avi-Yonah and Amos Kloner, “Mareshah (Marisa),” The New Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations in the Holy Land (1993).

John P. Peters and Hermann Thiersch, Painted Tombs in the Necropolis of Marissa (Mareshah) (London: Palestine Exploration Fund, 1905), p. 3.

This material was brought to London by courier on October 3, 1902. See the letter from Lagrange to Wilson of the same date in the archives of the Palestine Exploration Fund. The material was subsequently returned to the Dominicans and was kept together at the École Biblique in Jerusalem until 1974. That year the drawings were lent to two Israeli visitors to the École, who said that they wished to use them for a republication or restoration project. Neither the individuals nor the valuable colour drawings have been seen again by their rightful owners (personal communication from Father Jean-Baptiste Humbert, head of Archaeology at the École Biblique, April 30, 2001).

Marjorie Susan Venit, Monumental Tombs of Ancient Alexandria: The Theater of the Dead (Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 2002), pp. 22–67.

In 1993 the Israel Antiquities Authority restored the interiors of Tombs I and II, as part of a project to turn the area around Tell Sandahannah into a national park. The paintings have been recreated on a layer of concrete reinforced with fibreglass, applied as a cladding to the walls. Artist Haim Kapchik used the colored lithographs in Painted Tombs for his renditions. See Amos Kloner, Yadin Roman and Ya’acov Shkolnik, “Tomb with a View,” Eretz, volume 8, no. 3, 1993.

This sepulchral chamber finds certain parallels, in terms of its decorative features, among Hellenistic and Etruscan tombs. See Paul G.P. Meyboom, The Nile Mosaic of Palestrina: Early Evidence of Egyptian Religion in Italy (Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1995), p. 374, n. 25.

Philostratus, Life of Apollonius of Tyana, lii 48. For this reason, the griffin is often represented together with real animals in classical art. See Jocelyn M.C. Toynbee, Animals in Roman Life and Art (London: Thames and Hudson, 1973), pp. 28–29.

Scholars have remarked on the small size of this elephant in relation to the adjacent rhinoceros. It is now known that the strain of African elephant that was imported into Ptolemaic Egypt was not of the large Bush or Savannah, but a smaller forest species that populated the coastal and sub-desert areas of the Horn of Africa. See Howard Hayes Scullard, The Elephant in the Greek and Roman World (London: Thames and Hudson, 1974), pp. 23–25 and 60–63. In height and weight the Forest elephant is fairly close to the main variety of Indian elephant, but slightly smaller, as several classical authors maintain. See Polybius v 84; Pliny, Natural History, viii 9 (32); Diodorus Siculus, ii 16, 4; Strabo, xv 1, 43. Formerly the Forest elephant was believed to be an African sub-species, but recent research has shown that the genetic differences between the Forest and Savannah elephants are sufficient to justify classifying them as distinct species; see A.L. Roca et al, “Genetic Evidence for Two Species of Elephant in Africa,” Science 293, 2001, pp. 1473–77. It has a darker grey coloring, its ears are more rounded than those of its larger African relative. The elephant portrayed in this painting most closely approximates to this smaller species, which survives precariously in isolated pockets of west and central Africa.

The most famous examples from the Hellenistic period are the painted frieze on the attic of Tomb II (“Tomb of Philip II”) at Vergina, the ancient Macedonian capital of Aigai, and the reliefs on two sides of the Alexander Sarcophagus from Tyre, both dated to the last third of the fourth century B.C.E. On the painted frieze on the façade of Tomb II at Vergina, see Manolis Andronicos, Vergina, the Royal Tombs and the Ancient City (Athens: Ekdotike Athenon, 1989), pp. 106–19 and figures 64–71. On the Alexander Sarcophagus from Tyre, see Jerome J. Pollitt, Art in the Hellenistic Age (Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 1986), pp. 38–39.

Wiktor Andrzej Daszewski, Corpus of Mosaics from Egypt I: Hellenistic and Early Roman Period (Mainz: Philipp von Zabern, 1985), pp. 103–110, plates 4–5, 10–12; Daszewski, “Some problems of early mosaics from Egypt,” in Herwig Maehler and Volker M. Strocka, eds., Das Ptolemäische Ägypten, Akten des internationalen Symposions, 27–29 September 1976 in Berlin (Mainz: Philipp von Zabern, 1978) pp. 128–35; figures 116, 119–21.

Daszewski, Corpus of Mosaics, p. 103, plates. 10–12; Daszewski, “Some problems of early mosaics from Egypt,” p. 129, figures 119–21.

Daszewski refers to two of the felines as panther-griffins. See Corpus of Mosaics p. 103. However, the features that he identifies as horns are more logically the hair-tufts of the lynx, shown in stylised form.

Werner Hass, Ägypten in hellenistischer Zeit (München: C.H. Beck, 2001), pp. 288–89, 366–67, 425.

Strabo xvi 4, 5; 7; Diodorus Siculus iii 26–27; 36, 3; Paul G.P. Meyboom, The Nile Mosaic of Palestrina: Early Evidence of Egyptian Religion in Italy (Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1995), pp. 289–91, n. 44–45, 47; Stanley M. Burstein, Agatharchides of Cnidus On the Erythraean Sea (London: Hakluyt Society, 1989), pp. 4–12.

Meyboom, The Nile Mosaic of Palestrina (Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1995), pp. 290–291, n. 46, 49; Burstein, Agatharchides of Cnidus On the Erythraean Sea, pp. 4–12.

Athenaeus, Deipnosophists v 197C-202A. See Ellen Elizabeth Rice The Grand Procession of Ptolemy Philadelphius (Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, 1983). This procession probably took place in the first half of the third century B.C.E. Victoria Foertmeyer (“The dating of the Pompe of Ptolemy II Philadelphus,” in Historia 37 [1988], pp. 90–104) dates it to 275–4 B.C.E., while Richard A. Hazzard (Imagination of a Monarchy: Studies in Ptolemaic Propaganda [Toronto: Univ. of Toronto Press, 2000], pp. 59–79) believes that this procession took place in 262 B.C.E.

Animals accompanying Dionysus in his retinue stand in sharp contrast to one another. The bull, goat and ass symbolize fertility and sexual desire, while the lion, panther and lynx symbolize a bloodthirsty desire to kill. See Walter F. Otto, Dionysiac Myth and Cult (Bloomington: Indiana Univ. Press, 1965), pp. 110–111.

Hölbl, p. 171. The devotion of Ptolemy IV to Dionysus is attested to in Greek historical texts, including 3 Maccabees 2:28–29. The strong incentive offered by this monarch to the Jews of Alexandria to participate in Dionysiac mysteries is mentioned in 3 Maccabees 2:30, namely the granting of equal civic rights with the citizens of the metropolis.

Hölbl. p. 171; Martin P. Nilsson, The Dionysiac Mysteries of the Hellenistic and Roman Age (Lund: C.W.K. Gleerup, 1957), pp. 11–12.

David M. Jacobson, The Hellenistic Paintings of Marisa (London: Oxbow Books/Palestine Exploration Fund), forthcoming.