“In the fourth year of his reign over Israel, Solomon began to build the House of the Lord” (1 Kings 6:1). Bible scholars call this the First Temple. King Solomon built this Temple on the Temple Mount in Jerusalem, on a stone threshing floor bought by Solomon’s father, David, for 50 shekels of silver from Araunah the Jebusite (2 Samuel 24:18–25).

The First Temple stood on the Temple Mount for more than 350 years, until its destruction by the Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar, in 586 B.C. Second Kings relates that Nebuchadnezzar “carried off from Jerusalem all the treasures of the House of the Lord and the treasures of the royal palace; he stripped off all the golden decorations of the Temple of the Lord—which King Solomon of Israel had made—as the Lord had warned” (2 Kings 24:13). Nebuzaradan, the Babylonian chief of the guards, “burned the House of the Lord, the king’s palace, and all the houses of Jerusalem” (2 Kings 25:9).

The Babylonians “exiled all of Jerusalem [to Babylon]: all the commanders and all the warriors—ten thousand exiles—as well as all the craftsmen and smiths; only the poorest people in the land were left” (2 Kings 24:14).

Then in 539 B.C., in the first year of the reign of King Cyrus of Persia, an edict was issued by the king:

“All the kingdoms of the earth the Lord God of heaven has given me. And he has commanded me to build Him a house at Jerusalem which is in Judah” (Ezra 1:2).

“King Cyrus also brought out the articles of the house of the Lord, which Nebuchadnezzar had taken from Jerusalem … thirty gold platters, one thousand silver platters, twenty-nine knives, thirty gold basins, four hundred and ten silver basins … and one thousand other articles” (Ezra 1:7, 9, 10).

According to the Bible, there were successive waves of repatriations of Jews under Persian rule. The first was led by Sheshbazzar, the son of King Jehoiachin, who had been taken into captivity in 597 B.C. This first return, marking the beginning of a new era in the history of Israel—the Second Temple period—occurred not long after 539 B.C., when Cyrus issued his decree to start rebuilding the Temple in Jerusalem. Sheshbazzar was entrusted with the Temple vessels (Ezra 1:7, 5:14–15) and is reported to have laid the foundation for the rebuilt Temple (Ezra 5:16). The actual work of rebuilding the Temple, however, remained uncompleted.

A major wave of returning exiles was then led by Zerubbabel, grandson of Jehoiachin, and by the priest Joshua/Jehoshua, apparently during the early years of the administration of the Persian king Darius (522–486 B.C.). In the second year of Darius’s reign, Zerubbabel and Joshua established an altar on the Temple Mount in Jerusalem and began their work of Temple construction.

“The house [Temple] was finished on the third of the month of Adar in the sixth year [516/5 B.C.] of the reign of King Darius. The Israelites, the priests, and the Levites, and all the other exiles celebrated the dedication of the House of God with joy” (Ezra 6:15–16).

Some 60 years later, during the reign of King Artaxerxes (465/4–424/3 B.C.), Ezra and Nehemiah came to Jerusalem, Ezra as a “scribe skilled in the law of Moses” (Ezra 7:6), and Nehemiah as governor of Judea. Of Nehemiah’s varied accomplishments during those turbulent times, the one for which he is most remembered is rebuilding the walls of Jerusalem—a major move in the establishment of national security and a political statement that Nehemiah’s adversaries understood very well.

In 37 B.C. Herod the Great became king of Judea. In keeping with the grandeur of his building plans throughout his kingdom, he completely rebuilt the 500-year-old Temple. Herod’s rebuilding of the Jerusalem Temple both enlarged and glorified it. With thousands of workmen, the work started in the 18th year of his reign (20/19 B.C.) and was completed after 17 months, during the year 18 B.C., so we are told by the first-century A.D. Jewish historian Flavius Josephus. This Temple was destroyed by the Romans in 70 A.D.

Detailed descriptions of Herod’s Temple have come down to us in tractate Middot of the Mishnaha and in the two principal works of Josephus, The Jewish Wars (a detailed description of the First Jewish Revolt against Rome, 66–74 A.D.) and Antiquities of the Jews (a history of Israel from the beginning to Josephus’s time).

Tractate Middot is attributed to Rabbi Eliezer ben Jacob, a tannab who lived at the end of the Second Temple period and who had firsthand knowledge of the Herodian Temple before it was destroyed. His description is generally thought to be realistic, although some scholars claim that it is idealized.

A comparison of the descriptions in Middot and in Josephus reveals certain discrepancies, as does a comparison between Josephus’s own descriptions in The Jewish Wars and Antiquities of the Jews. The differences relate, for the most part, to the dimensions of the Temple’s apertures and of certain parts of the Temple. Taken as a whole, however, all three sources generally agree with one another. Josephus is conversant not only with the essential elements of the Temple—the Portico (ulam; sometimes translated “porch”), the Sanctuary (heikhal) and the Holy of Holies (kodesh hakodashim)—but also with the Upper Chamber, the cells and even the mesibbah, or stepped passageway, referred to in tractate Middot. Because the differences between Middot and Josephus are not fundamental,1 we can use details supplied in one source to supplement the others. Using these sources we can reconstruct, with great fidelity, Herod’s Temple, the Temple that Jesus knew.

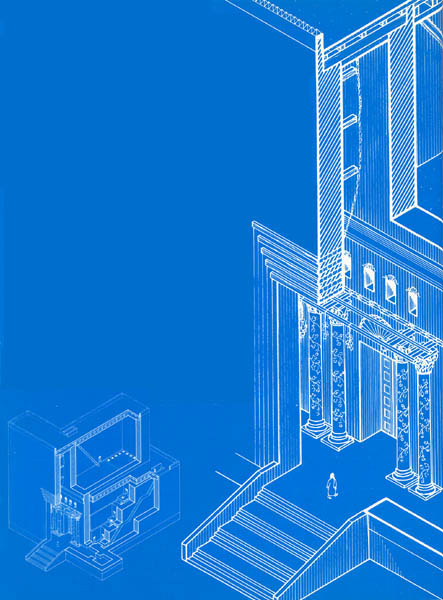

Our reconstruction aspires to a degree of detail never before achieved: a precise scale drawing of the Temple as a whole, as well as of each of its components. We attempt to remain faithful to the descriptions found in the sources and to refrain from hypotheses not grounded in these written sources. We present in our drawings not only our innovations, but all the parts of the Temple, as they may be understood from tractate Middot and Josephus. In the following description of the elements of the Temple, we frequently have not indicated the source of our information so as to preserve the flow of the discussion. But in this article you will find a sidebar with source references from Middot and from Josephus’s writings related to the individual architectural elements of the Temple.

Before examining the sidebar to this article to see the architectural details of Herod’s Temple—room by room—let us try to envision it as a whole.

The splendors of Herod’s Temple made a tremendous impression on all who saw it. Rabbinic sages taught: “Whoever has not seen Jerusalem in her splendor has never seen a lovely city. He who has not seen the Temple in its full construction has never seen a glorious building in his life.”2 And again in another tractate of the Talmud: “He who has not seen the Temple of Herod has never seen a beautiful building.”3

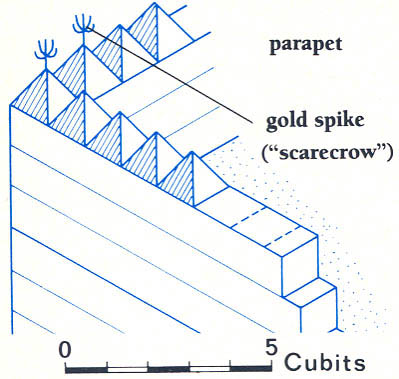

What made the exterior of the Temple so magnificent? The Talmud informs us that, according to one opinion, it was constructed of yellow and white marble, or, according to a second opinion, of blue, yellow and white marble. Mention is also made of Herod’s intention to cover the edifice with gold. And in fact, Josephus relates that the entire facade was covered with massive plates of gold; at sunrise, the Temple facade radiated so fierce a flash that persons straining to look at it were compelled to avert their eyes in order not to be blinded. The other walls were also plated with gold, but only in the lower sections. The upper parts of the building were of purest white, so that, from a distance, the building looked like a snow-clad mountain. Presumably, this effect was achieved by the application of whitewash to the upper section of the building, renewed once a year before Passover (Middot 3:4). Gold spikes lined the parapet wall on the roof. Such was the external splendor of the Temple.

Interestingly enough, neither ornately decorated columns nor capitals nor friezes with reliefs are mentioned, either on the facade or on the other sides of the building. Therefore one cannot claim that it is the exterior facade of the Temple that is depicted on the Bar-Kokhba coin. This coin clearly shows four columns and capitals, two on each side of an entryway. We believe these are the columns standing in the Portico before the Sanctuary entrance. (See the discussion of the columns earlier in this article)

However, another coin (below) from the time of the Second Jewish Revolt probably represents the exterior facade of the Temple. The Temple’s facade was on the eastern side of the building—facing the rising sun. From east to west, on the lowest level, the Temple consisted of the Portico, the Sanctuary and the Holy of Holies. An Upper Chamber extended above the Sanctuary and the Holy of Holies. Surrounding the Sanctuary and the Holy of Holies on the north, west and south were cells—small windowless rooms—arranged in three stories. The cells did not surround the Upper Chamber, so that beyond the Portico, the Temple was wider in the lower part than in the level.

On the northern side, beyond the cells but within the exterior wall of the Temple, was the mesibbah, or stepped passageway, leading from the front of the building up to the roof at the back of the building. The counterpart of the mesibbah on the southern side was a channel for draining away water from the roof (beit horadat hamayim).

The Portico was the widest part of the Temple. In Middotc it is said, “The Sanctuary [here referring to the Temple in its entirety] was narrow behind and wide in front and it was like a lion …” (Middot 4:7).

Exact dimensions of the Temple components are recorded in Middot. The measurements are all given in cubits.d Describing the overall exterior dimensions, Middot observes: “And the Sanctuary [including the Portico and the Holy of Holies] was a hundred cubits (172 feet) by a hundred cubits with a height of a hundred cubits” (Middot 4:6). The interior dimensions are specified from bottom to top, from north to south and from east to west. The horizontal dimensions are given at the level of the second story of the cells, as if a horizontal slice was made across the Temple at this level. Using the dimensions, summarized in the first sidebar to this article, we were able to produce scale drawings of the Temple plan viewed from above, drawings of cross-sections, as if looking at the surface of vertical north-south and east-west slices, and precise renderings of certain features.

We are ready now to consider, in detail, the architectural elements of Herod’s Temple. As you read what follows, refer to the drawings throughout the article in order to visualize, as we have, how the Temple appeared to those who lived in Jerusalem and to those who came as pilgrims three times each year to celebrate the festivals of Sukkot (Feast of Tabernacles), Shavuot (Feast of Weeks) and Pesach (Passover, the festival of the Exodus from Egypt). Our descriptions will proceed from east to west, as if we were approaching and then entering the awesome Temple.

The Outer Facade and the Portico (ulam)

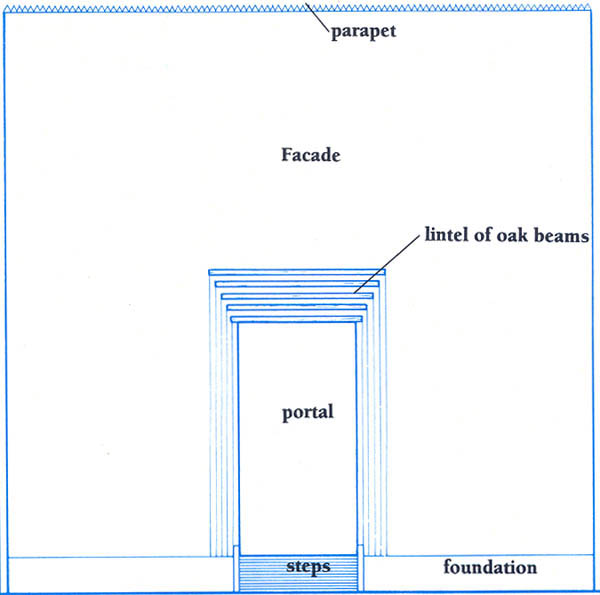

Twelve steps led up to the entrance to the Portico. Each step was 0.5 cubit (10 inches) high, so that the floor of the Portico was 6 cubits (10 feet) above the level of the Court of the Priests, an outside courtyard that surrounded the Temple. Six cubits is exactly the height of the substructure—the solid foundation upon which the walls of the Temple stood. The facade of the Portico was a plain, square surface, 100 cubits (172 feet) to a side, interrupted only at its center by an impressively large portal with a lintel above it. Aside from the fact that the facade was covered with gold, there is no information in the sources as to additional ornamentation, with the exception of the lintel above the entrance. The portal was 40 cubits (69 feet) high and 20 cubits (34 feet) wide. Neither doors nor curtains covered the opening. Like the entire outer surface of the facade, the inner walls of the portal were gilded. The lintel of the portal was constructed with five, one-cubit-thick, carved oak beams (maltera’ot, from the Greek, meaning primary ceiling beam) placed one above the other. The beams extended through the entire thickness of the facade wall and were separated from each other by courses of stones, each course one cubit high. The lowest beam was 22 cubits (38 feet) in length, the shortest of the five; each subsequent beam extended an additional cubit on each end, so that the topmost was 30 cubits (52 feet) long.

A portal of this kind is depicted on a rather rare, silver di-drachma coin (see photo of silver di-drachma coin) minted by Bar-Kokhba, the leader of the Second Jewish Revolt against Rome (132–135 A.D.).4 Although the Herodian Temple had already been destroyed for more than 60 years when these coins were minted, the memory of it was still relatively fresh. The depiction on these coins almost certainly represents the entrance to the Portico, with stairs in front and a lintel diagonally cut at its ends. What appear to be two columns may simply be doorposts of the entryway into the Portico. It was above this entrance that Herod set the golden eagle, which was later removed by pious Jews, but only at the end of his reign.5

As mentioned above, the facade of the Portico was 100 cubits (172 feet) wide. After passing through the open portal, one entered the Portico itself, a long, narrow anteroom extending from north to south along the entire width of the building; it was 11 cubits (19 feet) across from east to west. The walls of three sides of this anteroom were 5 cubits (9 feet) thick. (The wall of the Sanctuary, opposite the Portico facade, was 6 cubits [10 feet] thick.) The Portico extended to the full height of the Temple, 85 cubits (146 feet) from the floor to the ceiling.

The Portico exceeded the width of the Sanctuary of the Temple by 15 cubits (26 feet) on each side. The excess width, which stuck out like wings, formed two rooms, one at each end of the Portico, called the Chambers of the Slaughter Knives (beit

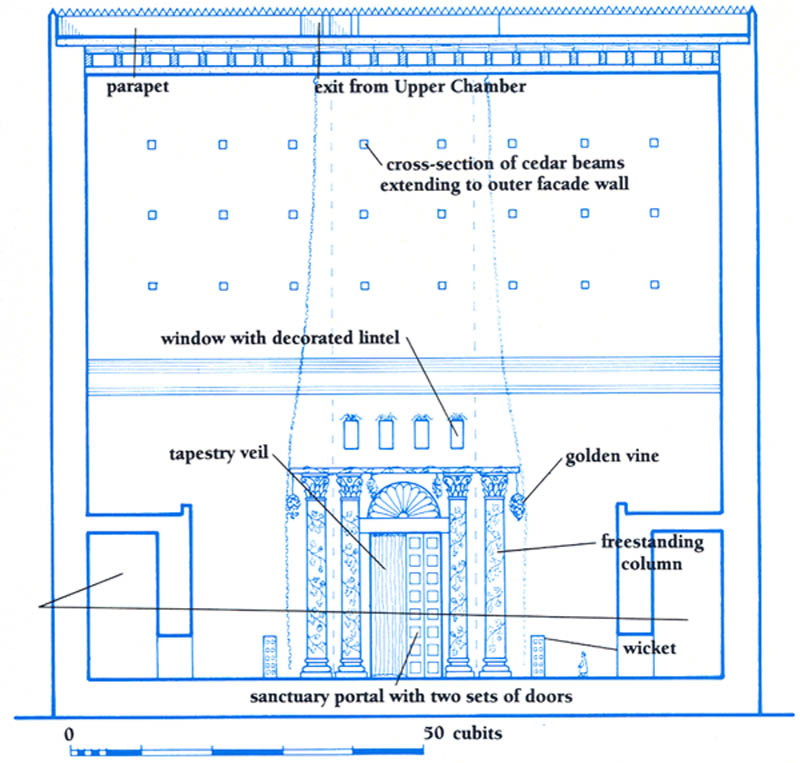

The eastern Portico wall—that is, the Temple facade—measured from the top of the solid basement to the top of the roof parapet, was 94 cubits (162 feet) high (85 cubits [146 feet] from floor to ceiling and 9 more cubits [15 feet] of roof construction and parapet), but only 5 cubits (9 feet) thick-or perhaps I should say thin, because 5 cubits is very thin to support a wall of this great height. In order to prevent collapse of such a tall but thin wall, cedar beams were set between the Portico facade wall and the Sanctuary wall. The drawings above and in the second sidebar illustrate one of several possible arrangements for these beams.

The Sanctuary Facade and Portal

On the facade of the Sanctuary itself—unlike the almost unadorned and less sacred Portico facade—Herod expended great effort and expense on magnificent decorations.

In the center of the Sanctuary facade wall was the portal, 20 cubits, (34 feet) high and 10 cubits (17 feet) wide. This wall was 6 cubits (10 feet) thick.

Two sets of panel doors controlled access to the Sanctuary—one exterior and one interior (see drawing of the facade of the sanctuary). Each panel door was 5 cubits (9 feet) wide. The exterior panel doors opened inwards, almost covering the 6-cubit (10-foot) thickness of the wall; the interior panel doors opened into the Sanctuary itself, resting on the inside wall of the Sanctuary (

The Sanctuary facade and the portal doors were all overlaid with gold.

On each side of the portal was a small, low wicket or doorway (see the drawing of the facade of the sanctuary and the second sidebar to this article). The northern wicket led into a cell from which one could enter the Sanctuary.e (The cells will be described in full later in this article) The southern wicket was sealed, having never been used.

The Column and the Golden Vine (see the drawing of the facade of the sanctuary and the second sidebar to this article)

Between the low wickets and the large entrance doorway into the Sanctuary, we have reconstructed four columns, two on each side of the main doorway, freestanding in the open area of the Portico. Columns are mentioned in this place only in the Latin version of Antiquities of the Jews 15. 394–395, describing the golden vine (see below). The number of columns, however, is not specified in this passage of Josephus. At this point, our reconstruction is based on the depiction of the portal on the Bar-Kokhba tetra-drachma (see photo of tetra-drachma) and upon a fresco above the Holy Ark in the early third-century A.D. Dura-Europos synagogue, excavated in the 1930s in Syria. Both the coin and the fresco appear to refer to the Temple, and they clearly have four columns. In placing the columns where we have, we differ from other scholars,6 who consider these depictions as representations of the exterior facade of the Temple rather than of the Sanctuary facade. However, as was mentioned above, no such decoration is mentioned in our sources, when describing the Temple’s facade.

The people of Israel are often compared to a vine, as for example in Jeremiah 2:21: “I planted you with noble vines, all with choicest seed; alas I find you changed into a base, an alien vine.” (See also Psalm 80:9–12 and Ezekiel 17:5–8.) A huge golden vine stood above the portal of the Sanctuary. Middot 3:8 tells us, “A golden vine stood over the entrance to the Sanctuary, trained over posts ….” According to Josephus (The Jewish Wars), “[The opening of the Sanctuary] had above it those golden vines, from which depended grape-clusters as tall as a man.” Antiquities of the Jews provides further details:

“He [Herod] decorated the doors of the entrance and the sections over the opening with a multicolored ornamentation and also with curtains, in accordance with the size of the Temple and made flowers of gold surrounding columns, atop which stretched a vine, from which golden clusters of grapes were suspended.”7

Our reconstruction of the golden vine, trained over columns, is based upon this description by Josephus.

The golden vine made a great impression upon foreign visitors to Jerusalem, as well, and is mentioned in the late first-century/early second-century A.D. writings of Florus and Tacitus,8 when they refer to the 63 B.C. conquest of Jerusalem by Pompey.

Adding to the weight of gold of the vine itself, freewill donations and vow-offerings of gold were also hung on the vine. The statement in Middot, that in view of the great weight of the gold, “three hundred priests were appointed” to remove it, maybe somewhat exaggerated; however, Josephus, describing the vine itself, claims that the golden grape clusters were the size of a man, so that a specially massive structure was needed in order to bear the weight of the tendrils and the clusters that hung above the 20-cubit-high (34-foot) portal.

Some of the Bar-Kokhba tetra-drachma coins show a wavy ornamentation above the horizontal beams straddling four columns, a motif that may be interpreted as the tendrils of a vine. Neither the hanging clusters nor the grape leaves are depicted on these coins; they do appear, however, as the central motif in other Bar-Kokhba coins of lower denominations (see below). The strip of half-circles that appears in the third-century A.D. fresco of the Dura-Europos synagogue, at the top of the facade, is probably a late transformation of the golden Vine.

The Curtain the Golden Lamp and the Tables

A veil of Babylonian tapestry, woven and embroidered in four colors—scarlet (tola’at shani), light brown (shesh) blue (tchelet) and purple (argaman)—hung at the entrance of the Sanctuary (see drawing of the facade of the sanctuary). The colors were highly symbolic: tola‘at shani, a scarlet dye extracted from the scarlet worm, symbolized fire; shesh, a fine linen in its natural color, represented the earth that produced the fiber; tchelet a blue dye extracted from snails, represented the air; argaman, a purple dye also extracted from snails, represented the sea from which it originated. The veil portrayed, Josephus say in The Jewish Wars 5.5, 4 (212–214), “a panorama of the heavens, the signs of the Zodiac excepted.” The veil hung on the outside and was visible even when the doors of the Sanctuary were closed. In the Hellenistic period, before the erection of the Herodian Temple, the veil had hung on a long golden rod concealed in a wooden beam. In 53 B.C., this beam was given by the priest responsible for the veils to Crassus, governor of Syria. The false hope of the priest was that his bribe would prevent further looting of the Temple treasures (Antiquities of the Jews 14. 105–109).

In front of the veil, at the entrance to the Sanctuary, hung a golden lamp—a gift of Queen Helena of Adiabene (in what is now northern Iraq). Two tables also graced the entrance in front of the veil, one of marble and the other of gold. On the marble table, the priest placed the new shewbread to be introduced into the Temple, and on the gold one, the old bread, which had been brought out of the Sanctuary. (On the di-drachma coin) The object between the doorposts of the open entryway may be a table or tables, standing before the Sanctuary entrance on the western side of the Portico.

In our reconstruction we have shown four windows above the portal of the Sanctuary (see the drawing of the facade of the sanctuary and the second sidebar to this article). We know from Middot 3:8 that golden chains hung from the ceiling of the Portico to be used by the young priests to climb up and inspect, repair and clean window decorations. Above each of the four window lintels, my reconstruction shows a decoration, wreath- or crown-like ornaments attached to the wall. Middot 3:8 implies that there were four such crowns, reminiscent of those fashioned from the silver and gold collected from the returnees from the Babylonian Exile, and placed upon the head of Jehozadok the High Priest (Zechariah 6:14).

Those who stood in the Court of the Priests outside the Temple could look through the wide, high opening, into the Portico and see the exquisite golden ornaments hanging on the Sanctuary facade, as well as the tapestry veil and the tables with shewbread. But they could not see into the Sanctuary.

The Sanctuary (heikhal) and the Holy of Holies (kodesh hakodashim)

The Sanctuary and the Holy of Holies composed one long room, 60 cubits (103 feet) long, 20 cubits (35 feet) wide and 40 cubits (69 feet) high, separated by curtains. Entered from the Portico, the Sanctuary was 40 cubits long. It was separated from the Holy of Holies by two curtains (amah traksin) hung 1 cubit apart (see the second sidebar to this article). The eastern curtain—on the side of the Sanctuary—was slightly open at the southern end, while the western curtain—on the side of the Holy of Holies—was slightly open at its northern end, an arrangement that prevented unauthorized people from seeing the Holy of Holies. Only the High Priest was permitted to enter the Holy of Holies; to do so he passed through the space between the two curtains.

The very beautifully worked curtains, embroidered with lions and eagles, were displayed to the public before being hung in the Temple. As we find in Sheqalim 8:5, another tractate of the Mishnah:

“The veil was one handbreadth thick and was woven on [a loom having] seventy-two rods, and over each rod were twenty-four threads. Its length was forty cubits and its breadth twenty cubits; it was made by eighty-two young girls and they used to make two in every year; and three hundred priests immersed it [to purify it before hanging].”

The interior of the Sanctuary was completely overlaid in gold save only the area behind the doors. The overlay consisted of gold panels 1 cubit square and as thick as one gold denarius (a Roman coin). The gold panels were taken down at the three pilgrimage festivals and displayed outside, at the ascent to the Temple Mount, after which they were re-hung in the Sanctuary. Within the Sanctuary were the lampstand, the shewbread table (to be distinguished from the marble and gold tables in front of the entrance to the Sanctuary, mentioned previously), and the incense altar, all made of gold. The seven branches of the lampstand recalled the seven planets, while the 12 loaves of bread placed upon the Table of the Shewbread recalled the 12 signs of the Zodiac and the 12 months of the year. The altar held 13 different types of incense, taken from the sea, the desert and the earth.

The Holy of Holies was devoid of all furnishings. No one was permitted to enter or even look inside, save the High Priest and even he could do so only once a year, on the Day of Atonement (Yom Kippur), when he went in and out four separate time.9 The only thing inside the Holy of Holies was a rock, three fingers high, called even hashtiya, upon which the High Priest made incense offerings.

Artisans, on the other hand, who were responsible for the maintenance of the building, entered the Holy of Holies from above, in closed cages lowered from the Upper Chamber through openings (lulin) in the floor, cut right through the ceiling of the Holy of Holies (see the second sidebar to this article). The cages were closed on three sides and open only to the walls so as to prevent the artisans from stealing a glance into the Holy of Holies.

Contributions of gold, made in payment of vows, were set aside for the sole purpose of preparing the beaten gold sheets that covered the walls of the Holy of Holies.

Above the Sanctuary and the Holy of Holies was the Upper Chamber, while surrounding the Sanctuary and the Holy of Holies on three sides—north, west and south—were the cells. Together, the Upper Chamber and the cells enveloped the most sacred parts of the Temple on three sides and from above.

The Cells

The Sanctuary and the Holy of Holies were surrounded on three sides with small chambers, or rooms, that are referred to as cells. In all, there were 38 cells arranged in three stories. They were on each side and extended to the full height of the Sanctuary. The Upper Chamber (over the Sanctuary and Holy of Holies) remained unenveloped by cells.

Here is the description of the cells in Middot, which we guarantee you will understand if you read to the end of this article and look closely at the drawings:

“And there were thirty-eight cells there, fifteen to the north, fifteen to the south, and eight to the west Those to the north and those to the south were [built] five over five and five over them, and those to the west, three over three and two over them. And to every one were three entrances, one into the cell on the right, and one into the cell on the left, and one into the cell above it. And in the one at the north-eastern corner were five entrances: one into the cell on the right, and one into the cell above it, and one into the mesibbah and one into the wicket and one into the Sanctuary” (Middot 4:3).

The lowest story of cells stood on the same solid basement as the walls of the Portico and the Sanctuary.

Josephus also refers to cells arranged in three stories around the Sanctuary and the Holy of Holies, but not around the Upper Chamber: “Around the sides of the lower pan of the Sanctuary were numerous chambers, in three stories communicating with one another; these were approached by entrances from either side of the gateway. The upper pan of the building had no similar chambers, being proportionately narrower …” (The Jewish Wars 5.5, 5 (220–221).

Josephus mentions here neither the total number of cells nor their exact arrangement around the walls, but in reference to the Solomonic Temple (the First Temple) he refers to 30 cells that encompassed the building, a fact for which there is no Biblical source (Antiquities of the Jews 8.85). It is possible that this figure actually relates to the Temple of Josephus’s own times, but even then, only to the sum of the cells on the northern and southern sides (15 each, as stated in Middot).

We believe the description of the cells in Middot is the more accurate and we have adopted it in our reconstruction. On each of the long sides are 15 cells, five on each of the three floors. The cells are interconnected by openings. On the back of the building are similar cells in three stories, but only three on each of the first two floors and two on the third floor.

These cells were probably used for storage of ritual vessels, material required for the ritual itself (such as oil and spices), and for the Temple treasures. These same purposes could also have been served by many of the chambers in the courtyards round about the Temple. An interesting parallel to these cells is found in the “crypts” surrounding the Egyptian temple of Hathor in Dendara, as well as the temple of Horus at Edfu, also in Egypt, both belonging to the Hellenistic period and both completed in the first half of the first century B.C., shortly before the erection of Herod’s Temple.

The ceiling supports of the first and second stories of cells were not extended into the Sanctuary wall; instead, they rested upon 1-cubit-wide ledges on the exterior face of the Sanctuary wall (see the second sidebar to this article). The lower ledge was built out more than the upper one from the surface of the Sanctuary wall. Hence, from bottom to top the walls of the Sanctuary receded in steps. At the level of the lowest story, the Sanctuary wall was 7 cubits (12 feet) wide; at the level of the second story, 6 cubits (10 feet) wide; and at the level of the upper story, 5 cubits (9 feet) wide. Thus the cell rooms in each story had a different width depending on the thickness of the Sanctuary wall against which it was built: the first-story rooms, 5 cubits wide; the second, 6; and the third, 7 cubits.f

The Stepped Passageway (mesibbah), and the Water Drain (beit horadat hamayim)

Between the cells and the outer wall, on the northern side of the building, there was a 3-cubit-wide (5-foot) space called the mesibbah. A parallel space on the southern side, also 3 cubits wide, was called “the space for draining away the water” (beit horadat hamayim). The mesibbah ascended within the width of the wall. Josephus mentions this ascent, but only in conjunction with the Solomonic Temple (Antiquities of the Jews 8.70) and not as part of the Herodian Temple. As there is no Biblical support for the mesibbah as an element of Solomon’s Temple, we assume (as we assumed with Josephus’s description of the cells surrounding the Solomonic Temple) that Josephus was extrapolating from the Herodian Temple with which he was personally acquainted. According to our reconstruction (see the second sidebar to this article),10 the mesibbah was a sloping, stepped passageway 66 cubits (114 feet) long and 45 cubits (78 feet) high, leading from the ground level to the roof above the top story of cells. Each step had a rise of half a cubit (10 inches) and a tread of half cubit, according to the dimensions recorded in Middot 2:3. This allowed for the incorporation of a number of horizontal landings, with a total length of 21 cubits (36 feet). Our depiction assumes the following structure (from bottom to top): a landing 7 cubits (12 feet) long; a flight of stairs 14 cubits (24 feet) long; another landing of 7 cubits; another flight of 14 cubits; a third landing 7 cubits long; and a third flight up to the outer roof, 17 cubits (29 feet) long. This calculation places the three landings at the floor level of the three cell stones.

A mesibbah, in the form of a graded ascent within a wall, is found among the largest and most famous Hellenistic and Roman temples: for example, the Egyptian temples of Hathor in Dendara and of Horus in Edfu both have them; the palace-temple at Hatra in Parthia, the temples of Zeus in Baetocece (Hossn Solieman), Syria and Qasr Bint Fara‘un in Petra, the Nabatean capital also have them. And it is quite possible that Herod installed such an ascent at the temple of Augustus that he built in Sebaste (Samaria).

The “space for draining away the water,” in the southern wall, opposite the mesibbah, served to drain off the rain water from the Temple roofs (see the second sidebar to this article, plan of the temple’s lower story). It is reasonable to assume that this was a sloping channel that enabled the water from the cells’ roof to run off. Assuming symmetry, we would then suggest that the channel sloped downwards from west to east, like the mesibbah, but the opposite slope is also possibility. Such an ascent, with a moderate slope, could also have been used by workers to move building materials upward during the construction of the roof of the lower stories, as well as of the Upper Chamber which formed the second story of the Sanctuary. The workers might have made use of the mesibbah in the same manner. Moreover, the external walls as well as the cell walls, between which these ascending passageways ran, could serve both as scaffolding and “curtains in the courtyard,” concealing in this manner the building work going on within the Sanctuary and the Holy of Holies from the curious eyes of the people (Mishnah ‘Eduyot 8:6).

The Upper Chamber

The Upper Chamber, which formed a second story above the Sanctuary and the Holy of Holies, was 40 cubits (69 feet) high; its walls were cubits (9 feet) thick. A mosaic strip of paving (r‘ashei psifasin) 1 cubit (21 inches) wide, separated the eastern part of the Upper Chamber extending over. the Sanctuary from the western part over the Holy of Holies. Like the double curtain between the Sanctuary and the Holy Holies, a curtain probably hung here as well. The entrance to the Upper Chamber, reached by walking from the top of the mesibbah upon the roof of the cells, was on the south; the entrance itself certainly opened into the area over the Sanctuary rather than the area over the Holy of Holies. Close by the entrance were two cedar posts that served as a ladder by which one could climb to the roof of the Upper Chamber, 45 cubits (78 feet) above the floor level.

In the western Part of the Upper Chamber, above the Holy of Holies, there were chimneys (lulin) (see the second sidebar to this article) or holes cut in the floor, through which maintenance artisans were let down in boxes open only towards the walls of the Holy of Holies. In this way the workmen could not see inside the Holy of Holies.

In our reconstruction, these chimneys are 2 cubits (3 feet) square, 1 cubit away from the wall and 2 cubits from each other. These dimensions would have allowed the artisans to comfortably carry out their work of cleaning and repairing the walls with only minor overlapping of the surface area covered by any two adjacent chimneys.

The location of the chimneys, their dimensions and the spaces between them were dictated by the function they performed. On the other hand, the chimney location determined the layout of the beams supporting the ceilings of both the Sanctuary and the Holy of Holies. The main roofing beams, as well as the second layer of roof beams that crossed them, would have had to be positioned in such a way as to create squares of 3 x 3 cubits (5 x 5 feet), through which the chimney openings could be cut. These considerations led us to the solution proposed in our reconstruction of the roof of the Temple’s first story.

The Temple Roofs, the Parapet and the Scarecrow

The Temple had two levels of roofs: the lower level over the cells and the upper level over the Portico and the Upper Chamber (which itself was over the Sanctuary and the Holy of Holies). At the edges of both roofs was a 4-cubit-high (7-foot) Parapet, topped by 1-cubit-high gold spikes, intended to prevent ravens and other birds of Prey from perching, soiling the walls with droppings and interrupting the order of sacrifice. Middot refers to these spikes as “scarecrows”g (kalah ‘orev); the sages were divided as to whether they were included in the calculation of the 4-cubit-high parapet or were additional.

Installations of this sort to ward off birds of prey, are also found in temples of other nations where sacrifices formed an important pan of the cult. In our reconstruction, the upper course of the Parapet consists of stone pyramids 1 cubit square at the base and 1 cubit high. The golden spikes stood at the top of each pyramid, a design that we think would have achieved its aim as a bird repellant

The squared-off denticulated ornamentation commonly found on the top of temples is insufficient, in our opinion, to prevent birds of prey from perching there. We must assume that, in order to effectively keep birds away from the Temple precinct and from the freshly killed sacrifices that would attract them, it was necessary to install special devices not only on the Temple roofs but elsewhere around the altar.

We are not the first to render a reconstruction of the Second Temple in Jerusalem. Many have tried with more or less devotion to fact rather man fancy. But we believe that our reconstruction, intimately bound to a careful reading of those sources that contain “eyewitness” accounts may be as close as it is possible to come to depicting the Temple as we would have seen it gleaming in Jurusalem’s transparent light, 2,000 years ago.

(The photos of the di-drachma and tetra-drachma coins are published here by courtesy of the Israel Department Antiquities and Museums. The photos belong to the Israel Museum, and I am indebted to Prof. Ya‘akov Meshorer for permission to publish them. The photos of the bronze coins are published here by courtesy of the Institute of Archaeology, Hebrew University, Jerusalem.)

MLA Citation

Footnotes

The Mishnah is the compilation of Jewish oral law redacted, arranged and revised by Rabbi Judah HaNasi about 200 A.D. The Mishnah is divided into six orders; each order divided into tractates.

The Aramaic word tanna (plural, tannaim) generally designates a teacher mentioned in the Mishnah, or a sage who lived in mishnaic times, about 20–200 A.D.

One cubit equals 52.5 centimeters (20.67 inches). This cubit is called the long or royal cubit to distinguish it from the short cubit, which was about 45 centimeters. The use of two different cubits is reflected in the Bible. For a discussion of cubits mentioned in the Bible, see Gabriel Barkay, “Measurements in the Bible,“ in sidebar to “Jerusalem Tombs from the Days of the First Temple,” BAR 12:02.

Alternatively, one could pass through the wicket, then through a passage within the wall, into the space between the two sets of main doors to the Sanctuary.

The length of the cells is not mentioned in Middot. The present reconstruction assumes a barrier wall 4 cubits (7 feet) wide between the cells, and an overall length, on the north and south, equal to the length of the interior of the building; that is, 61 cubits (105 feet). The total length of the western cells was limited on the north and on the south by the cell walls, giving them a total length of 44 cubits (76 feet). Thus by subtracting the thickness of the divider walls from the proposed total length of the cells on the north and south and on the west and dividing by the total number of cells on each side, we arrive at 9 cubits (16 feet) for the length of the northern and southern cells in the three stories and 12 cubits (21 feet) for the length of the western cells on the first and second stories. It is not clear how the two cells of the western third story were divided; it may be that the division was asymmetrical so that they had different lengths.

The height of the cells is not recorded in Middot. It is possible to deduce from Middot 4:5 that the cells encompassed the entire height of the Sanctuary, since the roof surface of the cells is on exactly the same level as that of the floor the Upper Chamber. Presumably, the entire roof structure the third-story cells formed a continuation of the roof structure separating the lower level of the building from the Upper Chamber. This roof structure was 5 cubits (9 feet) thick. If we assume that the ceilings of the first and second cell-stories were 2 cubits (3 feet) thick each, then we are left with a space 12 cubits (21 feet) high for each cell. These are the measurements adopted in the present reconstruction. According to our assumption, these ceilings, which rested upon the walls of the Sanctuary, consisted of wooden beams that ran across the cells.

Endnotes

Many scholars, such as Emil Schürer, Kurt Watzinger, Abraham Schalit, Michael Avi-Yonah and others, find the Middot descriptions of the Temple preferrable to that provided by Josephus.

I am indebted to Prof. Dan Barag for bringing this coin to my attention. See also: Barag, “The Table for Shewbread and the Facade of the Temple on the Bar-Kokhba Coins,” Qadmoniot 20 (1987), pp. 22–25.

Kurt Watzinger. Michael Avi-Yonah, Yaakov Meshorer, Leo Mildenberg and Dan Barag, to mention just a few of them.

This translation by Lea Di Segni is from the Latin version, which, in this instance, is better than the corrupt Greek version.