Rings of Gold—Neither “Modest” Nor “Sensible”

028

Several passages in the New Testament discourage Christian women—and men—from adorning themselves with gold rings. But by the time the Christian movement became more secure—and wealthier—one Church father said gold rings were all right—at least for limited purposes.

The many gold rings that have been recovered from the first few centuries of the Common Eraa gorgeously illustrate what the debate was all about.

Many New Testament books reflect Christian origins among the poorer (or more frugal) classes. For example, Jesus tells his disciples not to worry about how they are dressed:

“Consider the lilies …. Even Solomon in all his glory was not arrayed like one of these. But if God so clothes the grass which is alive in the field today and tomorrow is thrown into the oven, how much more will he clothe you—you of little faith?” (Luke 12:27–28).

More specifically, women were admonished to adorn themselves “modestly and sensibly” and not with “gold” (1 Timothy 2:9). Wives were told not to festoon themselves with “decoration of gold” (1 Peter 3:3).

Men too were told that “gold rings” and “fine clothing” would only lead to unjustified distinctions and evil thoughts:

“For if a man with gold rings and in fine clothing comes into your assembly, and a poor man in shabby clothing also comes in, and if you pay attention to the one who wears the fine clothing and say, ‘Have a seat here, please,’ while you say to the poor man, ‘Stand there,’ or ‘Sit at my feet,’ have you not made distinctions among yourselves, and become judges with evil thoughts?” (James 2:2–4).

Gold rings were signs of wealth and status in the Greco-Roman world, and Christians turned away from competition for honor through display.

Gold rings served a variety of functions in the ancient world. Of course they were worn for personal adornment—to enhance one’s appearance and thereby influence and impress others—029something Christians were not to do. Gold rings also reflected wealth, in other words, economic power. For Christians, this should have been irrelevant—quite aside from the fact that few early Christians could afford such rings.

Gold rings also indicated social status in the Roman world. Until about the time of Augustus’ reign (27 B.C.E. to 14 C.E.), a gold ring on a Roman male citizen’s hand meant that he belonged to the second highest order of nobility, the knights. Imperial favorites of lower class were often appointed to the honor of wearing a gold ring. Yet a law of Tiberius’ reign (14–37 C.E.) tried to restrict the honor to only men whose father and grandfather had been free-born, wealthy knights. Nevertheless, soon afterwards, Pliny tells us, “people began to apply in crowds for this mark of rank.”1 Martial (40–104 C.E.), a writer of epigrams, ridicules former slaves who display the gold ring as a sign of their rise to the rank of rich knights.2 Eventually, from the time of Hadrian (117–138 C.E.), the gold ring was forbidden only to slaves.

From very early times, rings were use as a sign of authority and office. Early finger-rings from 030Egypt that were used to show rank often encase a scarab gem engraved with the image of a beetle. Pharaoh gave such a ring (

In the book of Esther, the Persian king Ahasuerus gives a royal signet ring (

The prophet Isaiah includes rings (

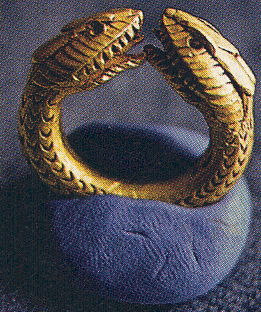

In Greece, gold rings have been found from as early as prehistoric times. Signet rings were especially popular in Athens in the fifth and fourth centuries B.C.E., with the increasing use of gold, precious jewels, and engraved designs. Even such austere persons as the orator Demosthenes and the philosopher Aristotle wore several at one time. Many of the rings from late classical and Hellenistic times are small in size, suggesting they belonged to women.

Pliny, writing in Rome, tells us that in the early days Romans wore only rings of iron.3 Gold rings were reserved to ambassadors sent abroad. By 216 B.C.E., however, Roman soldiers were wearing gold rings; during the Punic Wars with Carthage, Hannibal collected three pecks of gold rings from the fingers of Roman corpses.

Gold was, of course, not the only material from which rings were made. Greco-Roman rings of silver, bronze, iron and other materials have been found at various sites. As a kind of survival of the early days when Roman rings were made only of iron, plain iron rings were given to fiancees on their betrothal. By about 200 C.E., however, Tertullian refers to Roman betrothal rings of gold.4

Pliny also tells of people who “load[ed] the fingers with a wealthy revenue.”5 For women, the most valuable stones for rings were diamonds, pearls, emeralds, beryls and opals; for men, “it is an individual’s caprice that sets a value upon an individual stone, and above all, the rivalry that ensues.” The choice of gemstone was influenced not only by the value of the stone but also by a belief in its protective properties. Diamonds, for example, “prevail over poisons and render them powerless, 031dispel attacks of wild distraction and drive groundless fears from the mind.” Malachite “protects children.” Amethysts prevent drunkenness, assist people approaching kings as supplicants and, with incantation, keep off hail and locusts.

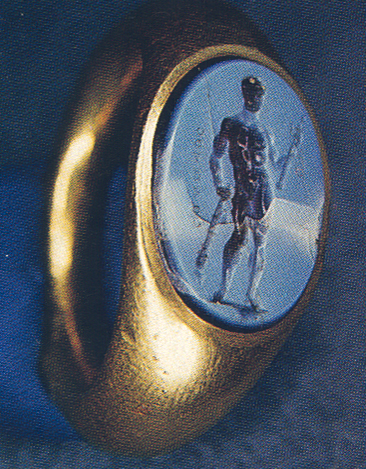

Roman rings, like Greek ones, were variously engraved with the names of the owners, portraits of ancestors or friends, religious images (deities or cult objects), allusions to one’s family history (real or mythical), objects from daily life and animals. Images could be engraved in the gold itself, or incised into stone or glass, or they could protrude in cameo fashion.

Julius Caesar’s ring included a picture of the goddess Venus in armor, an allusion to his mythical ancestor. Augustus used successively a sphinx, the head of Alexander the Great and finally his own portrait. Nero’s signet ring showed the god Apollo with the satyr Marsyas, whom Apollo skinned alive.

As seals these signet rings were variously applied. Letters were first bound in cords; then a dab of special earth or wax was placed on the cords and imprinted with the author’s seal both as a sign of authenticity to verify the identity of the originator and to attest that there had been no unauthorized opening or tampering. Wills and marriage agreements were also sealed in this way. Pliny mentions the widespread use of seals in concluding business contracts, referring to “the custom of the [crowd], among whom even at the present day a ring is whipped out when a contract is being made.”6 Boxes, jars, and storage areas were also protected by seals. “Nowadays,” Pliny tells us, “even articles of food and drink have to be protected against theft by means of rings.”

It is hardly any wonder that Christians were attracted to gold rings and other finery and adornments. Christian opposition to this way of life is reflected in the parable of the rich man dressed in expensive purple and fine linen who is punished after death for not sharing his food with Lazarus, the poor beggar with sores. (Luke 16:19–31). The book of Revelation depicts Rome as a woman “clothed in purple and scarlet, and adorned with gold and jewels and pearls, holding in her hand a cup full of abominations and the impurities of her fornication” (Revelation 17:4).

In 1 Timothy 2:9 and 1 Peter 3:3, women are told to avoid gold. 1 Timothy 2:9 contains an interesting pun on the Greek word kosmos, from which our words “cosmos” and “cosmetic” are both derived. Kosmos basically meant “order, good 032arrangement”; the cosmos is an “ordered universe.” When applied to women, kosmos implied modest, orderly, submissive behavior. Kosmos also meant “ornament, decoration, especially of women.” In Homer’s Iliad the queen of the gods, Hera, grooms herself and puts on fine clothes and Jewelry, “decking her body with all adornment [kosmos]” in order to seduce Zeus and distract him from the Trojan war. Perhaps we are now ready to appreciate the pun in 1 Timothy 2:9 ”[I desire] also that women should adorn [kosmein] themselves modestly and sensibly in seemly [kosmios] apparel, not with braided hair or gold or pearls or costly attire.” In short, not “adornment” [kosmein] but “seemliness” [kosmios] is recommended by a pun on the Greek stem kosm-.

By 200 C.E., things had changed, however. Clement of Alexandria, an early Church father, permits a Christian man or woman to wear a gold signet ring for the practical purpose of sealing documents or to secure storage areas. For him, signet rings are an everyday, accessory of life. Clement writes:

“[The World], then permits to them [women] a finger ring of gold. Nor is this for ornament [kosmos], but for sealing things which are worth keeping safe in the house, in the exercise of their charge of housekeeping.”7

This reversal is somewhat startling after the bias of the New testament against signs of wealth. The alteration reflects a change in the Christian community between the time of the New Testament and Clement’s time. Instead of being suspicious of wealth, Clement assumes his readers are financially well off; in fact, Clement devotes a separate treatise to arguing that wealth is not a disqualification for Christian salvation.8 In regard to rings, Clement assumes that the woman is mistress of a house-hold and will need to seal cupboards to prevent pilfering by servants.

Clement also reflects a tolerant attitude toward a woman’s adornment, provided its aim is to please her husband:

But there are circumstances in which this strictness may be relaxed. For allowance must sometimes be made in favor of those women who have not been fortunate in falling in with chaste husbands, and adorn themselves in order to please their husbands. But let desire for the admiration of their husbands alone be proposed as their aim.”

033

Opposed to Clement’s liberal attitude, however, was Tertullian, a contemporaneous Christian writer whose treatise On the Apparel of Women denounces women’s use of gold jewelry. Women, like Eve, are the devil’s gateway and should dress in sordid clothes as a sign of repentance. If gold had been available in Eve’s time, says Tertullian, she would have coveted it.

Clement also allowed men to wear rings—but, again, only for the utilitarian purpose of sealing items for security purposes. Addressing his male readers, he states,

“And if it is necessary for us, while engaged in public business, or discharging other avocations in the country and often away from our wives, to seal anything for the sake of safety, [the Word] allows us a signet for this purpose only.”

He quickly adds, however, “Other finger-rings are to be cast off.” A ring is to be used only for practical purposes, not for ostentation.

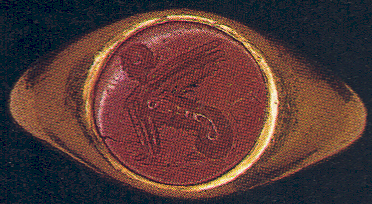

Clement’s advice is also interesting with respect to the symbols on signet rings that are appropriate for Christians. Pagan gods are prohibited. Some of the signs he recommends were easily understood from a Christian perspective. But there is no mention of a cross or the letters chi rho, a Christian symbol that later became common. He says:

“Let our seals be either a dove, or a fish, or a ship scudding before the wind, or a musical lyre, or a ship’s anchor, which Seleucus [a Hellenistic king] got engraved as a device; and if there be one fishing, he will remember the apostle and the children drawn out of the water.”

The dove and fish could be easily understood from a Christian perspective. The dove could be symbol of the Holy Spirit, which appeared at Jesus’ baptism (Matthew 3:16 and parallels). The fish could be linked with the apostle Peter, a former fisherman, as Clement says, or possibly identified with Christian believers emerging from the waters of baptism. Perhaps also about this time the acrostic spelling of “fish” in Greek (ichthys,

Clement forbids the use of pagan deities or symbols inappropriate to Christian moral values:

055

“For we are not to delineate the faces of idols, we who are prohibited to cleave to them; nor a sword, nor a bow, following as we do, peace; nor a drinking cup, being temperate. Many of the licentious have their lovers engraved or their mistresses, as if they wished to make it impossible ever to forget their amatory indulgences, by being perpetually put in mind of their licentiousness.”

While avoiding endorsements of pagan deities and customs that were immoral by Christian standards, Clement recognized that his Christian readers were nevertheless faced with the practical need— shared by their pagan neighbors—to use signet rings. Clement thus gives concrete advice for getting along in contemporary society, effectively and with good taste.

Several passages in the New Testament discourage Christian women—and men—from adorning themselves with gold rings. But by the time the Christian movement became more secure—and wealthier—one Church father said gold rings were all right—at least for limited purposes.

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Footnotes

Endnotes

Pliny the Elder, Natural History 33.33 (vol. 9), trans. H. Rackham, Loeb Classical Library (Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univ. Press, 1952).

Clement of Alexandria, The Instructor 3.57.1, in The Ante-Nicene Fathers, ed. A Roberts and J. Donaldson (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1986 [reprint]), vol. 2, p. 285. For the following Clement quotations, see Instructor 3.57–58 (pp. 285–286 in Roberts and Donaldson).