045

Liberty is conventionally thought to be a property of Western civilization. It is given dual genealogies, one biblical and the other Hellenic. The tale of how Israel was liberated from Egyptian domination is conjoined with the tale of how Athenians invented democracy to generate the myth opposing a free West to a despotic Orient. But this myth is an ideological construct, rather than an explanation informed by historical evidence. Ancient Near Eastern history discloses a more complex reality.

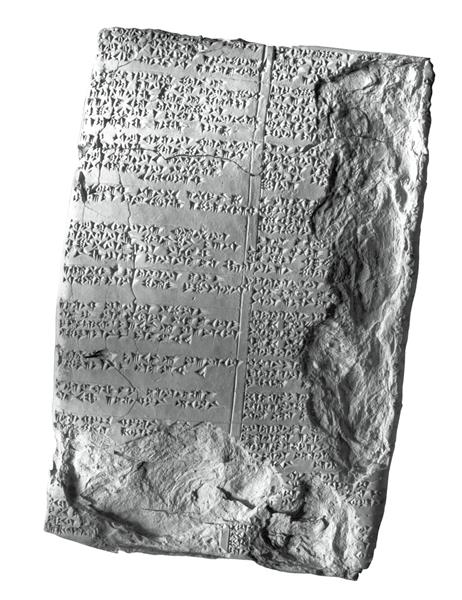

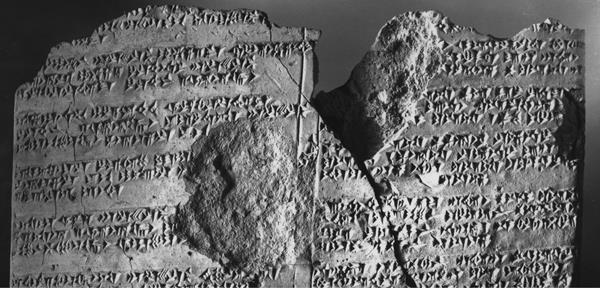

The most exciting new source is an epic poem that bears the ancient title Song of Liberation, originally composed in Hurrian around 1600 B.C.E. It was recorded in a bilingual Hurrian-Hittite edition, written in cuneiform on clay tablets around 1400 B.C.E. Fragments of this edition were excavated at the site of Hattusa, capital of the kingdom of Hatti, in 1983. Because the Hurrian language is poorly known and much of the text is lost, there are many uncertainties in the interpretation of what survives, especially where the Hittite translation is missing. Yet the extant pieces disclose an intriguing tale.1

The poem tells a story centering on the question of release from subjection within a political order in which citizens determined policy. One city, Ebla, had subjected the people of another city, Igingallish, and now the gods demand that Ebla let those 046people go. However, the senate of Ebla refuses, exercising its own liberty as a body of free men to deny liberty to the people of Igingallish, who serve them.

What kind of subjection did the people of Igingallish suffer, and to what condition did the gods demand they be released? And why did this interest the scribes of Hatti who wrote the poem down two centuries later?

The key term in the poem’s title is kirenzi in Hurrian, an abstract noun meaning “release,” which was rendered into Hittite with the verb para tarnumar, “to release, hand over.” The Hurrian word kirenzi translates Akkadian anduraru, meaning “return to original state,” and the Akkadian word in turn translates Sumerian amar-gi, which literally means “return to mother.” The biblical Hebrew cognate of Akkadian anduraru is deror, meaning “debt amnesty,” to which we will return later. The corresponding Greek term is seisachtheia, literally “shaking-off of burdens.”

Pragmatically, these terms refer to remitting noncommercial debts and reversing their consequences, that is, releasing persons from debt bondage and reversing foreclosures on mortgaged property. The semantics of the Sumerian and Semitic words point to the root concept of restoration to original state: a debt amnesty was meant to restore the people, their lands, indeed the state itself to their original and proper condition prior to the dislocations wrought by debt and analogous kinds of constraint.

In the early second millennium B.C.E., it was traditional for “restoration” to be proclaimed upon the death of one king and the accession of another, in order to reset the state of the realm by restoring everybody and their property to their point of origin. Remission of debts was but one concrete realization of the concept of restoration, and the term’s specific content depended on the context to which it was applied. The anduraru that released free persons from debt servitude returned slaves from creditors to their original masters; the anduraru that remitted taxes restored people to a condition prior to their subjection by the state; and the anduraru that freed people from foreign rule restored them to native rule. The term thus acquired the connotation “liberation,” although that was not its primary meaning.

Anduraru would be proclaimed upon the normal succession of a son to his father’s throne, but also upon accession through conquest or usurpation. The new king could thereby pose as the people’s benefactor by wiping their financial slates clean (if he could afford to alienate their creditors), or he could even proclaim himself the liberator of a subjected population. In its more prosaic sense of debt remission, anduraru could also be proclaimed ad hoc in the course of a king’s reign, presumably for political purposes. Archival documents show that such edicts were actually put into effect and debts were cancelled, foreclosures were reversed, and persons were sprung from bondage.

The practice of issuing edicts of “restoration” started in third-millennium B.C.E. Sumer, flourished in the multipolar world of the early second millennium, and continued, with lapses, into the first millennium. The term traveled from culture to culture picking up allegorical significance as it went. Its meaning could even extend to embrace its antithesis: 047Just as an anduraru decree could restore slaves taken in pledge to slavery with their original owners, the concept could be employed to mean “freeing” persons to serve a deity.

Thus, Hattusili I, founder of the Hittite kingdom in the late 17th century B.C.E., stated in his annals that, upon capturing the city of Hahhum, he liberated its people by devoting them to the service of the Sun Goddess of Arinna. The Akkadian version of his annals says that he established the captured people’s anduraru, while the Hittite version says that he exempted the people from labor duties and released them to serve the sun goddess. So he did not set the people of Hahhum free. They lost their autonomy with the Hittite conquest of their city, but Hattusili forwent his rights to their service by dedicating them to the goddess.

During the same series of campaigns, along the present-day border between Turkey and Syria, Hattusili visited Igingallish, which the Hittite version of his annals says he destroyed. This would have taken place around 1600 B.C.E., at about the time the archaeological record attests the destruction of Ebla, a long day’s march southwest of Aleppo. Nothing links Hattusili to Ebla, but Ebla’s fate is linked to Igingallish in the Song of Liberation. This poem develops a theological explanation for the destruction of Ebla. It may have been composed by the people of Igingallish—or of Ebla—who were taken captive in Hattusili’s campaign.

Two centuries later, Hittite scribes recorded the Song of Liberation in writing. They produced a bilingual edition in a series of tablets giving the Hurrian text on the left and the Hittite translation on the right. They provided them with colophons that give the title of the composition and a number denoting the tablet’s number in the manuscript at hand. They reproduced this edition in several complete or partial copies, perhaps for the purpose of instructing Hittite scribes in Hurrian. Fragments of these manuscripts were found, along with other tablets, in and around a temple in Hattusa upon which a Byzantine church was built millennia later.

Not one tablet of any of the manuscripts survives intact, and no complete manuscript can be put back together from the multitude of fragments. Reconstructing the original poem is therefore a tricky task—like doing a jigsaw puzzle with only a quarter of the pieces, which moreover come from different boxes—and many gaps remain. The tablets’ colophons, when preserved, are crucial to the reconstruction. For example, the fragment bearing the colophon “Tablet I of the Song of Liberation, not finished” (meaning the manuscript continues on the next tablet) clearly gives us the beginning of the poem. Most fragments, however, are missing their colophons.

Insofar as the story can be put together, it goes like this:

048

The poet begins by introducing the protagonists. “Of Teshub, great lord of Kumme, I shall sing,” he sings, invoking the storm god by his Hurrian name. The storm god, in Near Eastern cultures as well as in Greece, was traditionally concerned with justice. The other divine characters include Teshub’s sister Allani, goddess of the netherworld, and Ishhara, goddess of oaths and marriage (not to be confused with Ishtar, goddess of sexual love and war). The poet then introduces Pizigarra of Nineveh, whose role is lost in the missing text; it’s tempting to suggest that Pizigarra was a prophet, whom the gods called to Ebla. The other human characters include Megi, king of Ebla; Purra, leader or representative of the people of Igingallish; and Zazalla, speaker of the senate of Ebla, whom we meet in the climactic scene.

In the first preserved passage of the narrative, Teshub and Ishhara are discussing the fate of Ebla, but there the fragmentary tablet ends. Two other fragments may record parts of the next episodes. In one, we read about the activities of Teshub, who got out of bed, did something about a decree of liberation, spoke to his brother Shuwaliyat and urged him to go to Ebla, an instruction Ishhara repeats … but then it breaks off. In the other fragment, we read about Pizigarra, about the imprisonment of Purra, and about Purra being bound to a stone by Teshub.

Then comes a large fragment whose contents, preserved in Hurrian only, are continuous with those of a better-preserved tablet, in which Teshub is speaking to Megi, king of Ebla. In one passage of the Hurrian fragment, Teshub is recounting a series of kings who ruled Ebla and whom Purra—here called “the butler” (or the like)—has served. In another passage, Teshub seems to be preparing for his main theme by introducing paradigmatic examples, followed by rhetorical questions, such as, “For the one who continually grinds the millstone, shall there be no release on behalf of that one, too, the maidservant?”

The last lines of this fragment are identical to the first few lines of the next tablet, the most intact of the lot, which preserves substantial parts of both the Hurrian and Hittite columns. Now Teshub 049enunciates his injunction to release the people of Igingallish, as well as Purra, here called “the captive.” He has served three kings of Igingallish and six kings of Ebla, says Teshub; Megi is the tenth. Addressing the city of Ebla, Teshub promises military success and economic prosperity if they decree release, and utter annihilation of Ebla if they do not (see the sidebar below for this passage).

At this point there is a long lacuna, encompassing the bottom of the tablet’s obverse and much of its reverse. From the scant remnants of text at the lacuna’s edges it can be discerned that, Teshub’s speech having concluded, Megi speaks in response, and then he goes to address the senate of Ebla. “Listen,” Megi says, and proceeds to report Teshub’s message. When the text becomes fully legible again, Megi is quoting the god’s injunction, threat, and promise—and the tablet ends with a colophon identifying it as “[Tablet n of (the Song of) Lib]eration, not finished.”

A tiny fragment containing barely a dozen lines of its Hurrian column duplicates the end of that tablet and the beginning of another big fragment, thus establishing the sequence of the narrative. The text of the big fragment in turn partly duplicates that of another tablet, identified by its colophon as “Tablet V of ‘Liberation,’ not finished.” And now we arrive at the climactic scene in which the king’s proposal to fulfill the god’s command is answered in the senate by its preeminent speaker, Zazalla (see sidebar below for this passage).

The poet introduces Zazalla as a powerful speaker whom none can best in argument. He opposes Megi, saying, “Why do you speak submission?” He asks 050ironically whether Teshub himself is oppressed, so that he needs release. If Teshub needs money, Zazalla says, the senate will give him some; likewise, if he is hungry, naked, or parched, they will provide for the god. But they will not release the people of Igingallish, who are their servants. Zazalla challenges Megi to release his own slaves, give his wife back to her father, and even cast out his son—implying that the release Megi demands is tantamount to breaking the bonds of social relations. This explains why Ishhara, goddess of oaths and marriage, was involved in the gods’ decision that Ebla must let the people of Igingallish go.

Faced with the senate’s opposition, Megi goes weeping before Teshub and reports the result: “I grant it, but my city does not grant release,” he says. “Megi purified himself,” the poet says, “casting the sin upon Ebla.” Then the tablet breaks off.

What may be the next episode is partly preserved in a fragment that reports Teshub’s visit to the palace of his sister Allani, goddess of the netherworld. He is received with honor, seated on a throne, and there at the bolts of the netherworld Allani prepares for him a banquet of mythical proportions. She seats on his right the Primeval Deities, whom he had vanquished in the battles through which he had attained kingship of the gods. Allani herself serves as her brother’s cupbearer and serves him a drink in a fancy cup … and the text breaks off. The remains of a colophon identify this tablet as “[Tablet n of] Liberation […] the singer […] not finished.” So, the banquet in the netherworld was not the last act in the drama.

Had Teshub already fulfilled his threat to destroy Ebla, or was that still to come? Although it is narrated in no surviving fragment, the destruction of Ebla must indeed have ensued upon the senate’s refusal to do the gods’ will and release the people of Igingallish.

That may have been the end of Ebla but the beginning of a new theme in poetic discourse. The conflict between king and senate exposes a conflict between sociopolitical ideals. Against Megi’s demand to restore equity by releasing people from subjection, Zazalla argues for preserving a rule-based order that establishes relations of dominance and subordination. What then was the reason for the imperative of release?

Subjection could be legitimate, whether it resulted from conquest, the provision of credit, or the exercise of lawful authority. It should have a limit, however, so that the creditor could not keep indebted persons forever in servitude, and the ruling authority could not exact unlimited service or impose unlimited dominion. The term of bondage should last no longer than the period commensurate with the sum of the debt or the price of the subject, after which the gods would require the party in power to pay—for the subjects were originally theirs. Hence the god demands that the secular ruler “let my people go, so that they may worship me” (to quote the words of Yahweh to Pharaoh in Exodus 8:1, Exodus 20).

But they were not to exit bondage only to enter servitude with a god or a temple. They were to be 051restored to freedom. The gods require justice among men, and permanent subjection of free men is unjust. This is the theme of the Song of Liberation.

This is also a theme of biblical prophecy. The eighth-century prophet Amos informs the Israelites that their God takes no pleasure in their offerings; he does not need them to feed him—contra Zazalla’s offer to provide for Teshub—and desires instead that they do justice. Jeremiah, prophesying in Jerusalem more than a century later, communicates the same message on a specific occasion of injustice: Zedekiah, king of Judah, had accomplished what Megi did not and had obtained the assent of the ruling class to effect debt amnesty (deror, in Hebrew). After first releasing enslaved Judaeans, however, they forced them back into servitude. Their perfidy brought upon them Yahweh’s wrath, so that he decided to destroy Judah by the hand of the Babylonians and make it desolate of habitation, just as Teshub did to Ebla.

The same theme appears in the poetry of Solon, Jeremiah’s near-contemporary in Athens. Solon warned that it was not Zeus who would destroy Athens but its own citizens, who by their rapacity and injustice would bring divine retribution upon themselves and cause their city to fall into slavery. From this calamity Solon saved his city by proclaiming seisachtheia, releasing her citizens from the servitude into which they had been sold for debt and releasing the earth herself, groaning under the weight of foreclosed mortgages, from her bondage.

The question arises why Hittite scribes wrote down the Song of Liberation when they did, just as the kingdom of Hatti began to acquire an empire. The poem epitomizes the political history of the Late Bronze Age (c. 1550–1200 B.C.E.), during which the ideal of free men constituting free polities was increasingly threatened by the hierarchical organization of states and subjects under imperial rule. Imperial sovereignty overrode constituent autonomy, disempowering local dynasties and collective-governance bodies in favor of appointed monarchs answerable only to the overlord. The issue of political subjection versus autonomy was one that Hatti increasingly confronted as it acquired an empire, and this may explain the interest of Hittite literati in a composition that dealt with exactly this theme.

It cannot be taken for granted that a poem like the Song of Liberation would take written form. In fact, textualization was a dead end, for poetry lived in performance and memory, not in writing. This poem was apparently composed and transmitted orally for generations before it was written down—and for centuries afterward, too. Whether it was sung in Hurrian or Hittite or other tongues, some version of it was transmitted from land to land and from language to language until its motifs and its very turns of phrase found new expression in classical Hebrew prophecy and archaic Greek political thinking. Indeed, its core theme reappears in the foundation myth of ancient Israel, whose archetypal leader conveyed to an implacable oppressor God’s demand to let his people go—or else.

Liberty is conventionally thought to be a property of Western civilization. It is given dual genealogies, one biblical and the other Hellenic. The tale of how Israel was liberated from Egyptian domination is conjoined with the tale of how Athenians invented democracy to generate the myth opposing a free West to a despotic Orient. But this myth is an ideological construct, rather than an explanation informed by historical evidence. Ancient Near Eastern history discloses a more complex reality. The most exciting new source is an epic poem that bears the ancient title Song of Liberation, originally composed in Hurrian […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username