Archaeology is full of surprises. Sometimes we don’t find what we had expected to find. Or we find something we never expected to find. Either way, the experience is always exciting—and wonderful.

A good case in point is our excavation at Khirbet Yattir (khirbet is Arabic for “ruins of”), a ten-acre mound in southern Judah. We were attracted to Khirbet Yattir because it was a virgin site. It lies just west of the Green Line, which marks the pre-1967 border of Israel. That probably accounts for the fact that it had never been excavated; until the 1967 Six-Day War, it was too dangerous. We knew the ancient name of the site; it is preserved along with the name of the Bedouin sheikh el-‘Atiri, whose tomb is on top of the site.

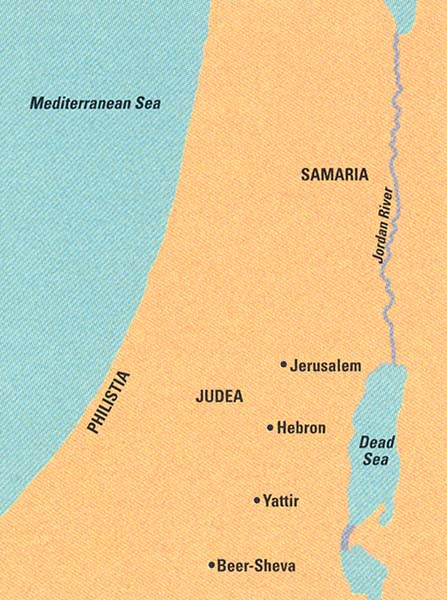

Yattir (often spelled Jattir in translation) has several Biblical connections. Located between Hebron and Beer-Sheva, Yattir is listed, along with many other cities and villages, among the tribal allocations in Joshua (15:48, 21:14). Yattir is also mentioned in the Bible when David is ostensibly fighting for the Philistine leader Achish; David sends booty obtained from the enemies of the Philistines (and of Judah) to the elders of Yattir, among other places (1 Samuel 30:27). Yattir was also a levitical city, and therefore a place of refuge (1 Chronicles 6:57).

The village next appears in the writings of church historian and theologian Eusebius in the fourth century C.E. He mentions seven Jewish villages and two Christian villages in the southern Judean highlands, then known as the Darom or Daroma. One village, which he calls Iethira (the Greek name of Yattir), he describes as “a large Christian village.”1He claims that there were only three Christian villages in all of Palestine at that time. It thus seems that Yattir became Christian relatively early.

These references led us to expect major strata from the Biblical period (the Iron Age; 1200–587 B.C.E.) and from the fourth century C.E. So far we have found neither.

Some Iron Age pottery has turned up, mostly from the seventh century B.C.E., but we have seen no architecture that we can firmly date to the Iron Age. We have found almost no pottery from the fourth century C.E. This means that we have no archaeological remains associated with the Christian village of Eusebius’s time. What we did find, however, were two imposing churches from the late sixth and seventh centuries C.E., one with a magnificent mosaic pavement offers unique insights into early Christianity.

What about Biblical Yattir? And what about the large Christian village that Eusebius talks about? Does this mean that the Bible is wrong? Or that Eusebius is making up stories?

Hardly. All it means is that we haven’t found those levels at Yattir yet—or that they may have been destroyed. We have recovered pottery from as early as 4000 B.C.E. (the Chalcolithic period) and 3000 B.C.E. (Early Bronze Age I) in our excavations, as well as pottery from the Persian period (c. 539–332 B.C.E.), the Hellenistic period (332–63 B.C.E.) and the early Roman period (63 B.C.E.–135 C.E.). It is clear that Yattir has a long history, much of it undocumented in the ancient sources. It is important not to reach conclusions too quickly based on the absence of evidence.

Yattir was built on a limestone hill covered by a layer of chalk. The ancient remains encircle the eastern side of the hill, forming a crescent that leaves the western slope bare. The inhabitants of Yattir cut many caves into the soft, permeable chalk. At various times, these caves were used as dwellings, as cisterns for storing water, as storage space for food and other goods and even as columbaria (caves with small niches cut into the walls, used for housing pigeons or doves). A number of presses in and around the site indicate the inhabitants also cultivated grapes and olives.

On a southern spur of the site, on the edge of the ancient village, we noticed four columns and the outline of an apse. This was too strong an inducement to resist. We excavated the area and exposed a fascinating church that had belonged to a monastery. The church consists of a basilical hall (with the apse at its eastern end), a narthex (porch) and an atrium (courtyard). This layout is characteristic of early Christian churches—and of many ancient synagogues as well.

The main hall of the church is divided by two rows of six columns each into a central area (the nave) and two side aisles. No two of the column pedestals are alike. Some of the columns have conical shaped capitals embossed with crosses; others have reused Nabatean-style capitals from the first century C.E.

All the rooms of the church were paved with well-preserved mosaic floors. Both the atrium and narthex were paved with plain white mosaic floors. In the main hall, the aisles have a simple white carpet decorated with stylized flowers. The mosaic in the apse, which is only partly preserved, has a geometric pattern.

The mosaic floor of the nave had two phases. All that is left of the earlier floor are four birds and medallions of vines. The later floor of the nave, however, has presented us with the star of our excavation so far—a complex, mostly intact carpet with 23 fascinating registers (see “The Yattir Mosaic: A Visual Journey to Christ,” in this issue). A complete 12-line Greek inscription in the mosaic near the entrance to the main hall reads:

This work was completed in the month of March in the sixth indiction [a 15-year cycle used as a chronological unit in the Byzantine period], year 526 of the era of the city, for the benefit of the salvation and the aid of Thomas the most holy, abbot of the monastery. [The work was done] by my hands, Zacharis, son of Yeshi, the builder, servant of God.2

This inscription identifies the church as a monastic church and provides a date. The inscription is dated according to the era of Provincia Arabia, which began in 106 C.E. By adding 526 years (the number in the inscription), we can date the pavement to 631/2 C.E.

Another complete Greek inscription, consisting of six lines, is set into the floor at the entrance to the basilica. It reads:

All of the work in building the church including the mosaic was carried out in the time of Yochanan [John] ben Zachariah, who honors God, the diakon, the head of the monastery, during the month of May in the ninth indiction in the year 483 according to the city’s calendar.

This confirms the nature of the church and provides a second date, the equivalent of 588/9 C.E.3 This suggests that the church was originally built in the late sixth century. The first mosaic floor was probably associated with this phase. Then, in 631, the floor of the nave was replaced on the eve of the Muslim conquest of 634.

The names in the inscriptions are also significant. Although Greek names such as Thomas are represented, the names Yochanan, Zachariah, Zacharis and Yeshi indicate that these Christian inhabitants of the village were of local, Semitic origin. Were these Judeo-Christians who inhabited Yattir? This seems unlikely. The split between Jews and Christians had occurred long before. There probably were no Judeo-Christians at this time. So who were these Christians? As usual, archaeology leaves us with as many questions as it answers.

Stray colored tessarae (the little cubes that make up a mosaic) on a terrace on the northwest slope of the tell alerted us to the possibility of a second church. Nearby was a stylized Corinthian capital lying on the ground. Searching among the ruins of 13th- to 14th-century houses on the slope below the terrace we found stone columns and pedestals. All of this suggested that a monumental building was located in this area. But was it another church? Once we started excavating, it became clear that the building closely resembled the monastic church we had already excavated—a basilical hall divided by two rows of columns into a nave and two aisles, with a narthex and an atrium. It too was entirely paved with mosaics.

During the 1997 and 1998 seasons, we could not decide whether this building was indeed a church. On the one hand, the fact that it was a monumental basilica of the Byzantine period suggested that it was. But several features puzzled us. First, we found no apse at the eastern end of the nave; if there once was one, it must have eroded down the slope with the rest of the east wall. Second, because most of the original floor was later replaced by plain white mosaics, no Christian symbols or inscriptions were preserved. Finally, and most importantly, it was not oriented due east like most early Christian churches. Instead, it was oriented about 40 degrees to the southeast. But perhaps this deviation was necessary to accommodate the building on the relatively limited area of the terrace.

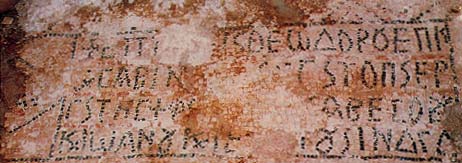

In the summer of 1999, the puzzle was solved. We uncovered a complete four-line Greek dedicatory inscription that reads:

In the days of the most holy Bishop Theodoros and Sabinios the Presbyter, all of the work on the mosaic was done [by] Absobo and Jonathan and Jeremiah in the fourteenth indiction.

The inscription is framed within a tabula ansata, a rectangular frame with triangular “ears” on either side. Although it confirms that the building was indeed another church, it does not include enough information to date the church. None of the people mentioned in the inscription is known otherwise.

The pottery that we found above the floor suggests that during the early Islamic period (eighth to ninth centuries), the building no longer functioned as a church; instead, it was someone’s home. Whoever lived here covered the Greek incriptions with plaster. Either then or perhaps earlier, the original floor was replaced with a plain, rather coarse white mosaic. The original mosaic floor, which was made with small colored tesserae, has survived in only a few isolated spots. In the northwest corner of the nave, for example, we found an eagle. Its wings are outstrechedand its head is turned towards the interior of the nave. It is framed within a panel bordered by a running swastika. Geometric designs are preserved around the edges of the nave.

What do these churches tell us about the early Christian population of Yattir? We are still working out the answers to that question. We know from both historical sources and archaeological evidence that a sizable Jewish population inhabited this area even after the Romans crushed the Bar Kokhba Revolt of 132–135 C.E.,4 but we know somewhat less about the development of the early Christian communities.

Of considerable interest to us is the rich array of symbols in the mosaic floor of the monastic church, which may help us learn more about the ideas and beliefs of incipient Christianity. In any case the excitement of archaeological discovery—and the surprise—inevitably give way to new questions, new ideas and new challenges.

MLA Citation

Endnotes

Eusebius, Onomasticon 11.4–9, in Ferdinand Larsow and Gustav Parthey, eds., Eusebii Pamphili Episcopi Caesariensis Onomasticon (Paris: Berolini, 1862), p. 233.

For more on the Darom and its villages, see Avi-Yonah, The Jews of Palestine, A Political History from the Bar Kokhba War to the Arab Conquest (Oxford: Blackwell, 1976), pp. 16, 139; Joshua Schwartz, Jewish Settlement in Judaea After the Bar-Kochba War Until the Arab Conquest (Jerusalem: Magnes, 1986), pp. 36–38, 41, 98–109 (in Hebrew); Yuval Baruch, “Tell Ziph and the Establishment of Christianity in the South of Hebron Mountain [sic],” in Yaakov Eschel, ed., Judea and Samaria Research Studies, Proceedings of the Eighth Annual Meeting, 1998 (Kedumim-Ariel: The Research Institute, College of Judea and Samaria, 1999), p. 180 (in Hebrew).

This inscription, as well as the one in the atrium and the one in Area D (see below), was read by E. Shenhav and Leah Di Segni.

The Byzantine method of dating according to the “indiction” was based on a 15-year cycle between assessments of property for purposes of taxation. Our date creates a two-year discrepancy between the two indiction years. We have not yet been able to resolve this discrepancy.

See, for example, Michael Avi-Yonah, The Holy Land from the Persian to the Arab Conquest (586 B.C.-A.D. 640): A Historical Geography (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker, 1977), p. 161: The Darom’s “distinguishing characteristic was that ut contained an unusually high number of Jewish settlements which had apparently survived Bar-Kokhba’s War.”