ZACHARY WONG, EL-ARAJ EXPEDITION

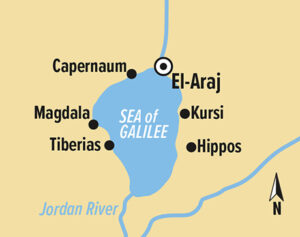

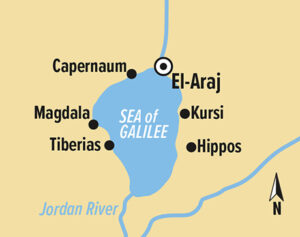

As BAR readers know, archaeologist Mordechai Aviam and I believe the site of El-Araj, on the northern shore of the Sea of Galilee near the estuary of the Jordan River, is biblical Bethsaida, remembered in the Gospel of John as the home of the apostles Peter, Andrew, and Philip (1:44). Our excavations at El-Araj have revealed a large Byzantine basilica and monastic complex built above the remains of an earlier, Roman-era fishing village from the first century CE. According to the Jewish historian Josephus, the village later expanded to become the Roman city of Bethsaida-Julias, which existed from the first to third centuries (Antiquities 18.28).

We believe the site’s archaeology as well as early Christian tradition and pilgrimage accounts confirm not only the site’s identification with Bethsaida but, perhaps more significantly, its location as the home of the apostle Peter.1 As we will see, this conclusion runs counter to modern claims that Peter’s house was commemorated by a small fifth-century octagonal church excavated at the nearby site of Capernaum and still visited today by pilgrims and tourists.

ZACHARY WONG, EL-ARAJ EXPEDITION

ZACHARY WONG, EL-ARAJ EXPEDITION

ZACHARY WONG, EL-ARAJ EXPEDITION

We begin with the archaeological finds from El-Araj that have resulted from the recent excavations conducted by Kinneret College and the Center for the Study of Ancient Judaism and Christian Origins. In 2021, we uncovered a significant Byzantine basilica that dates back to the sixth century, along with an adjoining monastic complex that may date a century earlier. The church, which measures approximately 70 by 60 feet, has a typical basilical plan with a central nave, two side aisles, and a single apse containing the main altar space. Throughout the church, we found large patches of colorful mosaic floor decorated with floral and geometric patterns as well as several Greek inscriptions: one in front of the apse, another in the center of the nave, and a third in the diaconicon (where church vessels and valuables were stored) located to the north of the apse. There were also various artifacts associated with early Christian worship, including parts of the marble chancel screen that separated the apse from the nave, and small pieces of gilded glass tesserae from an ornate mosaic that once decorated the wall of the basilica.

Around the church, we excavated a bathhouse and a number of rooms that likely served as living quarters for a monastery. A bathhouse and monastic complex were similarly found at the contemporary Byzantine church at nearby Kursi, which may have commemorated the site of Jesus’s “swine miracle” (Mark 5:1–20). The similarities between the two sites suggest that such major centers of Holy Land pilgrimage served both practical and spiritual needs.

—–

Clearly, the El-Araj basilica and its associated bath and monastery, like many contemporary Byzantine sacred sites, were built to commemorate places of importance to Christian pilgrims. But what biblical event or person was remembered at this site? We’ll return to that question once we first examine the various textual sources that identify Bethsaida with the home of the apostles.

Although only the Gospel of John explicitly identifies Bethsaida as the home of Peter, Andrew, and Philip (see sidebar below), early Christian sources from the fourth to eighth centuries, including the church fathers Eusebius (Proof of the Gospel 9.8; Onomasticon 58.11), Epiphanius (Panarion 51.15.5), John Chrysostom (Homilies on the Acts of the Apostles 4), and Jerome (On Illustrious Men 1), routinely describe Bethsaida as the home of St. Peter.

GARO NALBANDIAN

BILL SCHLEGEL/BIBLEPLACES.COM

We also have a number of Christian pilgrimage accounts that discuss Bethsaida and its location. The Byzantine pilgrim Theodosius, writing in 530, recounts his journey from Tiberias to Paneas (modern Banias) by way of Capernaum and Bethsaida, noting simply that Bethsaida was “where the apostles Peter, Andrew, Philip, and the sons of Zebedee were born.” Since Theodosius does not mention a church, it may be that the basilica at Bethsaida was not yet built when he visited. On the other hand, the presence of fifth-century coins beneath a pavement outside of the church suggests the monastery may have already been in existence.

Writing in 725, Willibald, a bishop from Eichstätt in Bavaria, is the first to explicitly mention a church at Bethsaida: “And [from Capernaum] they went to Bethsaida, from which came Peter and Andrew. There is now a church, where previously was their house.” Although Willibald’s itinerary around the Sea of Galilee resembles the pilgrimage of Theodosius, he additionally notes a church built over the apostles’ house at Bethsaida. He also recounts that he stayed overnight in Bethsaida, which may mean that he enjoyed the hospitality of the monastery and bathhouse.

ST. GALLEN, STIF TSBIBLIOTHEK, COD. SANG. 133, P. 608; USED BY PERMISSION

Yet we believe that there may be an even earlier reference to the Bethsaida church, namely in the itinerary of an anonymous pilgrim from Piacenza (Italy). The Piacenza Pilgrim recounts his journey in 570 around the Sea of Galilee: “Then we came to the city of Tiberias, where there are hot baths filling naturally with salt water, though the water of the sea itself is fresh. It is sixty miles around the sea. We also came to Capernaum, to the house of Saint Peter, which is now a basilica.”

Interestingly, the Piacenza Pilgrim’s account has generally been understood as referencing not a church at Bethsaida, but rather the fifth-century octagonal martyrium church at Capernaum, first studied by Gaudenzio Orfali in the 1920s and then later excavated by the Italian archaeologists Virgilio Corbo and Stanislao Loffreda.2 Consisting of two concentric octagons paved with beautiful mosaic floors, the church was built directly atop the remains of an earlier house church from the fourth century, which itself was built within the ruins of a small village house dated to the first century. The site’s interesting archaeology, along with the testimony of the Piacenza Pilgrim, led Orfali to propose that the martyrium church had been built to mark and commemorate the house of St. Peter.

But there are significant problems with interpreting the Capernaum church as the one visited by the Piacenza Pilgrim.

First, there is the obvious architectural problem that the octagonal church found at Capernaum is not a basilica, as de-scribed by the Piacenza Pilgrim. A basilica is an oblong hall with a double colonnade. We might think that the pilgrim was simply guilty of a loose use of terms, except that elsewhere in his itinerary, when he identifies a building as a basilica, it usually corresponds to the typical basilical plan. It is not impossible to imagine that in his account of the basilica, the Piacenza Pilgrim conflated Capernaum with nearby Bethsaida, where there is in fact a sixth-century basilica.

Second, the only time Capernaum is mentioned as the home of St. Peter in a pilgrimage account is in a purported excerpt from missing portions of the itinerary of the fourth-century pilgrim Egeria, as recorded by Peter the Deacon in the 12th century, who attributes his source to the eighth-century English monk Bede the Venerable: “Now in Capernaum there is a church from the house of the prince of the Apostles, whose walls still stand today. There the Lord healed the paralytic. There is also a synagogue where the Lord healed the demoniac, and to which one ascends many steps” (De locis sanctis 16.2).

Beyond the problem of the very late date for this witness, Peter the Deacon’s reliability as a faithful preserver of missing portions of Egeria’s itinerary has been seriously questioned. Indeed, as medievalist scholar Herbert Bloch has argued, many of Peter’s writings are little more than careless excerpts from other works or even outright forgeries.3

CASE CLOSED? This mosaic inscription written in Greek from the basilica at El-Araj commemorates a donor, “Constantine, the servant of Christ.” Even more intriguing, it implores the help of St. Peter, who is designated “the chief of the apostles and the keeper of the key of heaven.” This suggests the church had a special connection to the chief apostle, strengthening the claim that early Christians remembered Bethsaida (identified with El-Araj), not Capernaum, as the hometown of Peter, Andrew, and Philip.

There is, of course, a Byzantine church at Capernaum, but it does not appear to have been originally associated with the apostles. Epiphanius (d. 403 CE), the bishop of Salamis in Cyprus, reports that Joseph of Tiberias requested permission from Emperor Constantine to build churches in Galilee. He was permitted to build churches “in Tiberias, in Diocaes-area [i.e., Sepphoris], in Capernaum, and in the other cities” (Refutation of All Heresies 30.4.1). So, while this text does speak about a Byzantine church in Capernaum, there is no hint of its identification with Peter. Apostolic association may have come later, but it certainly did not exist earlier than the time of Bede (d. 735 CE) or, more likely, the medieval tradition of Peter the Deacon.

ZACHARY WONG, EL-ARAJ EXPEDITION

Given Willibald’s report of the church built over the house of Peter and Andrew at Bethsaida, together with the recent discovery of the Byzantine basilica at El-Araj, I believe it is far more likely that the Piacenza Pilgrim’s account references the El-Araj basilica rather than the octagonal church at Capernaum.

Fortunately, our excavations at El-Araj have finally confirmed the basilica’s association with St. Peter. The large Greek medallion inscription discovered in the church’s diaconicon names a local benefactor with an entreaty for intercession on his behalf from “the chief of the apostles and the keeper of the key of heaven.”4 In Byzantine writings, the title “chief of the apostles” is invariably identified with St. Peter,5 while the inscription’s reference to Peter as “the keeper of the key” clearly echoes Jesus’s promise to his apostle, “I will give you the keys of the kingdom of heaven” (Matthew 16:19).

A request for the apostle’s intercession intimates his close identification with the church. Peter’s association with churches in Byzantine Palestine is rare, typically occurring only at places with a connection to his appearances in the Gospels. The discovery of a petition to St. Peter in the basilica at El-Araj should remove any doubt that the church recalls the testimony of John 1:44—that the home of Peter, Andrew, and Philip was in Bethsaida. The church we have been excavating at El-Araj would then be the same one visited by Byzantine pilgrims to commemorate the home of the chief of the apostles.

In the next archaeological season, we plan to finish removing the mosaics in the church’s eastern apse, where there seem to be earlier structures buried under the sixth-century church. If these ruins date to the Roman period, they may belong to the house that early Christian tradition associated with the house of Peter. We will surely keep BAR readers updated.