The Philistines and the Dothans: An Archaeological Romance, Part 2

An interview with Moshe and Trude Dothan

040

In our previous issue (“The Philistines and the Dothans—An Archaeological Romance, Part 1,” BAR 19:04), archaeologists Moshe and Trude Dothan spoke with Hershel Shanks about their early years together, as were embarking on careers in archaeology and at the same time beginning a family They shared their impressions of the great women and men they knew who pact their stamp on archaeology in Israel. In this concluding installment, the Dothans talk in depth about their own research, focusing in particular on the legacy of the Philistines and other Sea Peoples.

041

Hershel Shanks: If you two had a nickname, it would be “Mr. and Mrs. Philistine.” You have worked a great deal of your professional lives on the Philistines. You have just written a book about the Philistines.a Do you think the Philistines have been treated unfairly in history?

Trude Dothan: If you call someone a Philistine, it is not exactly a compliment.

We are trying to show that a Philistine is definitely not somebody who has no culture, because archaeology shows the contrary. In the period when the Philistines were in Canaan—in Philistine proper, living beside Israel—Philistine material culture—its architecture, its arts—really ranks the highest, above the Israelites and above the Canaanites.

HS: Have you grown fond of the Philistines? Do you feel that you know the Philistines and that they’re friends?

Moshe Dothan: I like them. Incidentally, we have not only the Philistines; there are also other Sea Peoples who are very interesting. We don’t know too much about these other Sea Peoples because the Bible is not interested in them. The Bible is interested only in those people who are near Judah.

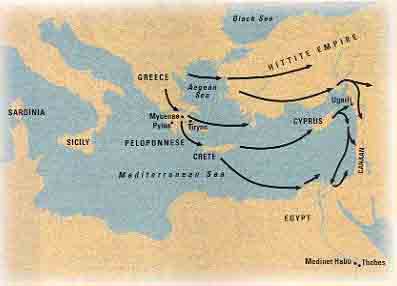

But there was an enormous movement of people in the 13th and 12th centuries [B.C.], covering not only this country but other countries as well.

HS: You have excavated sites and produced finds reflecting a particular civilization, but you never found an inscription in a Philistine site that says they are Philistine. Yet you label this pottery and other artifacts and architecture as Philistine. How do you know it is Philistine?

Trude: One of the goals of every archaeologist is to find the written word. To find an archive of the Philistines would be wonderful. We joke about it. Moshe has found the only inscription or written signs that may relate to a Philistine language. We haven’t found any written evidence at Ekronb yet. Neither has Larry Stager at Ashkelon.c Larry and the two of us talk about who is going to be the first to find a Philistine archive, but it will not be so easy. We are in a period where the written word is still rare; we are in the dark ages.

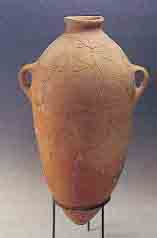

HS: Coming back to the question: You find a beautiful bichrome juglet with lovely paintings with birds and ducks with their heads turned backwards, and you tell me its Philistine. How do you know its Philistine?

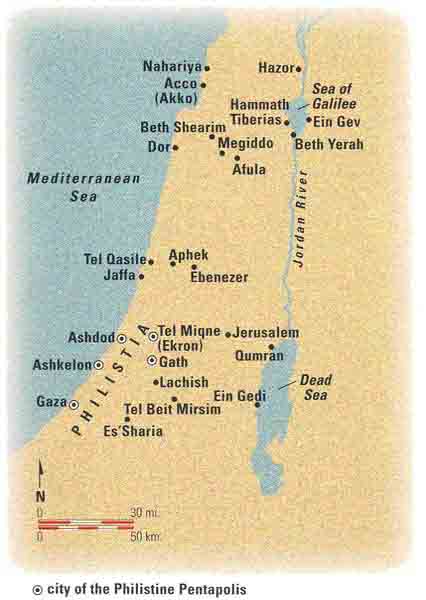

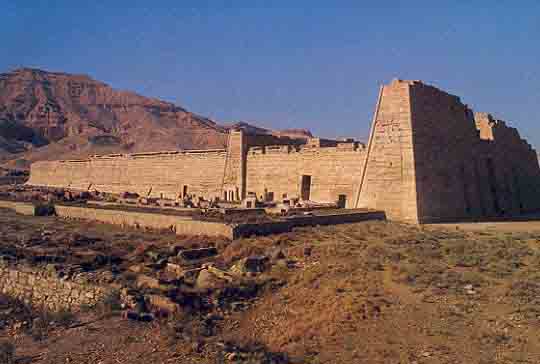

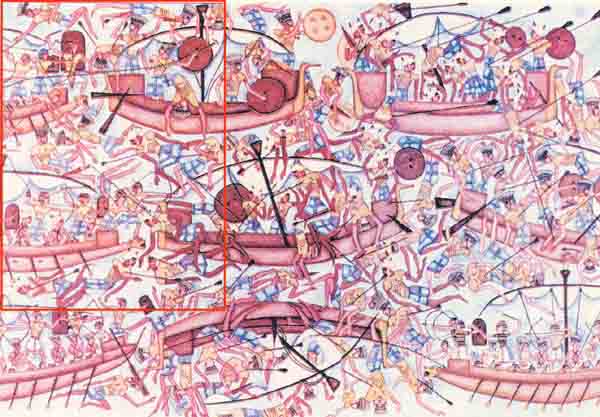

Trude: We don’t try to take just one component. The pottery is a kind of hallmark. It’s the most visible. It comes in the largest quantities. And from the pottery we can see the Aegean background of the culture. It’s like an enormous puzzle. There are many other things. In Egypt, at Medinet Habu, we have the depiction of the Philistines, the Sikila, of the Danuna, of the Shardana. There were many Sea Peoples, not just one, and we have them identified at Medinet Habu. Then we have chronology the time of Ramesses III [1175 B.C.]. Then we have the Bible. We have the Biblical stories. We have the names of the Philistine cities. We have the boundaries of Philistia proper.

HS: But I come back to the question: How do you know it’s Philistine?

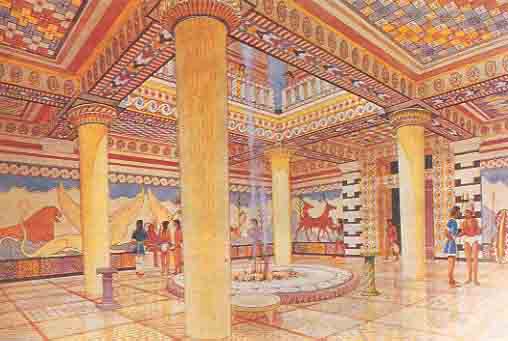

Trude: The chronological framework fits. The geographical framework fits. It fits with the Egyptian records. The Aegean background fits. We have excavated sites where we have Canaanite cities with their culture ending and a new culture coming in. This new people comes in, settles there, builds towns with new and different plans. It’s not just one thing—like pottery. There is a different type of cult building. We have a very rich, new ethnic element coming in, settling, building a new city—in Ashdod, in Ekron. They built a far larger city than the earlier Canaanite cities of the 13th century [B.C.]. From the very beginning, the new cities are well planned. They bring a new architecture. They have hearths in their houses, just like the hearths at Pylos and Mycenae [in Greece].

HS: In the central courtyard?

Trude: Yes. The hearth was the focal point of the palaces in the Aegean 042world. It was unknown in Canaan. The new people in Canaan didn’t bring the blueprint of the whole settlement, but they brought an architectural idea. This is a new feature in Canaan. I won’t go into all the small things that go with it. The important thing is that Philistia fits into the Biblical framework. It fits into what we know from Egyptian sources.

HS: You really know Philistia from the Biblical description. Isn’t that true?

Trude: Yes, that’s true.

HS: And when you dig there you find a distinctive civilization?

Trude: Yes. From the Bible, we know Ashdod, which kept its name [to modern times]. Ashkelon also kept its name. Ekron did not. But it can be identified with Tel Miqne. Gaza kept its name, but it has not been excavated. So three cities of the Philistine pentapolis kept their names.

We are in a period of coexistence of cultures. We have the Israelite settlements. We have a continuation of the Canaanite population. Egypt is still strong in this period. In Philistia proper, you get this very, very distinct entity. Then they expand.

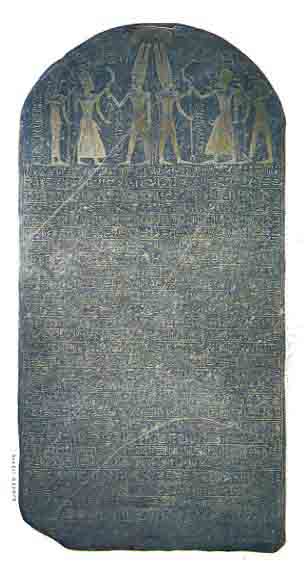

HS: I would like to make a comparison and then ask a question: At about the same time as you have the reference to the Philistines in Egypt at Medinet Habu, you have a reference to another people called the Israelites. It is on the Merneptah Stele in Egypt.

Trude: The Merneptah Stele is even earlier.

HS: The Merneptah Stele is 1207 [B.C.]? When is the Medinet Habu inscription?

Trude: The first half of the 12th century.

HS: About 1175 [B.C.]?

Trude: But the Sea Peoples had already been around for a long time. The inscription mentions the final victory of the Egyptians over the Sea Peoples.

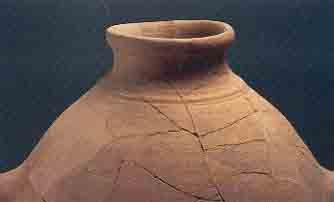

HS: So we are really talking about the same time. In the Bible we have a description of where the Philistines settled in Canaan. We also have a description of where the Israelites settled in the central hill country of Canaan—which fits with the mention of Israel in the Merneptah Stele. In the central hill country, we also find a kind of distinctive pottery (the collar-rim jar) and architecture (the four room house). The question I want to ask is this: Everyone seems to accept without question the existence of the Philistines, that this culture which you excavate in Philistia, and which you call Philistine, is Philistine. Yet there seems to be so much question about the Israelites in the adjacent hill country. Why?

Trude: I really don’t want to tread on a very difficult problem, which, I must say, I can’t answer. The problem is different with the Israelites. Take the material culture. What used to be called Israelite pottery—the collar-rim jar—we now find in Jordan too. So from pottery, I would say be very cautious. You can say more on the basis of the pattern of settlement. The new hill country settlements are in a kind of vacuum area. The new settlements are small. The architecture of the buildings is, again, however, a big problem. It is found not only in the central hill country. So it is the pattern of settlement, it is the time period, it is the area where the new settlements are, more than the material culture we find in these settlements, that tells us who the people were.

HS: Do you have any question about 043whether the new settlements in the central hill country of Canaan that were contemporaneous with the settlements in Philistia are Israelite settlements?

Trude: I really must say that there is nothing more difficult than the problem of ethnicity.

HS: You have no problem with Philistine ethnicity, yet you have a problem with the Israelites?

Trude: I didn’t say I have. I think there is a time around the 12th century that you have a coexistence of cultures. Some have a more distinctive material culture than others. I do think the Israelite settlements are well-defined. But they are well-defined more by the way they are dispersed, by the character of the whole settlement—by their initial paucity, by their being small and in areas that had not been previously settled—than by the pottery and architecture. So there are other hallmarks for identifying Israelite settlements than for identifying Philistine cities.

But it’s the same question: How do you define a new ethnic element? And it’s not clean-cut. In a Philistine city, the Canaanite population was not thrown out. It definitely continued. We find a continuation of local Canaanite traditions as well as new elements. This is also true in the central hill country with the Israelites. If you look, for example, at the cooking pots and the coarse ware, these continue. In Philistia, I think it was only the elite society that is very different, but there is no doubt there is also the continuation of Canaanite material culture. The same is true in the Israelite settlements. There is definitely a continuation of local traditions in the pottery although not in much more. The same is true in the cities in Canaan that were Egyptian, like Beth-Shean or Lachish or in Esh-Shari’a. There you have the continuation of the Egyptian impact. Whether for a longer or short period, you have different entities coexisting.

In Philistia, it is very striking because the newcomers brought with them a very rich, distinctive, flourishing culture. The Israelite settlements in the hill country are more enigmatic, more difficult. Your question is a good one and it is relevant. We are searching for ways to identify new ethnic groups archaeologically, to understand archaeologically the phenomenon of a new group of settlers—whether it’s a slow development or a quick one, whether populations coexist or are destroyed, and so on.

HS: There is a kind of symmetry between the two peoples coming in about the same time. But the issue of “coming in” is a little different in each case. There is no question that the Philistines, who were one of the Sea Peoples, “came in” to Canaan from outside; yet, in the case of the Israelites, although the Bible pictures them as “coming in” from outside, there is a great deal of 044controversy as to whether they really did “come in” from outside or whether they were local refugees from Canaanite cities. Why is there that difference between the Philistines and Israelites?

Trude: Archaeologically, I think these are parallel phenomena. With the Philistines there is the same kind of argument, although maybe less vehement than about the Israelites. We tend now in archaeology not to see things in such a clean-cut way—you know, these are the Israelites; these are the Philistines. We try to think in a larger framework, as part of a more general phenomenon, and questions arise. It’s no longer clear that the Israelites “came in” and conquered, and so on. Many scholars now see it as a social development, as a pattern of development. It is not one thing or two things, but several. And it is a slow development. For the Philistines, it’s more drastic. You can see the change more easily archaeologically.

HS: Moshe, you mentioned a number of other Sea Peoples. They are not referred to in the Bible, are they?

Moshe: No, they are not mentioned in the Bible, but they are mentioned in Egyptian sources.

HS: Along with the Philistines?

Moshe: Along with the Philistines. They are very interesting. I am sure that some of them settled in Canaan.

HS: According to the Egyptian inscriptions?

Moshe: No, they don’t say where they settled. We don’t know what happened to all these people whom the Egyptians were fighting. They have to be somewhere. We are lucky that we have the Bible, and the Bible tells us about the Philistines. I stress this again and again. The Bible is really the source for so much of our knowledge. Of course, the Bible doesn’t answer all our questions. But we have the stories about the Philistines, about Samson and so on. 045They are not just stories; they have some background. And the Bible tells where these people lived. In exactly those places, we find this culture we call Philistine. This can’t be any other culture.

HS: Since the Bible does not mention any Sea Peoples except the Philistines, how do you know, for example, that a site was occupied by one of the other Sea Peoples? Why don’t you identify it as Philistine also? And what are these other sites settled by other Sea Peoples?

Moshe: The majority of the Sea Peoples who settled in this country in the late 13th and early part of the 12th century were Philistines. We know this from the Egyptian records. After some very prolonged fighting, Ramesses III settled them here.d There are some years for which we don’t have any evidence as to what was going on in Egypt. We know only that it was a very bad time for the Egyptians. Something happened for perhaps 10 or 20 years and then most of the Egyptian rulers were gone from this country. Somebody came in. They have to be the Sea People. In the Bible, I think Philistine is a generic term for more than one tribe of Sea Peoples.

HS: I understand that at Tell Qasile, for example, which is within the city limits of Tel Aviv today, it was not the Philistines but another Sea People. Similarly at Dor, farther north on the coast, another Sea People settled there. Is that correct?

Moshe: Yes.

HS: Who were the other Sea Peoples at these sites?

Moshe: There are at least two we are certain of. One is called the Sikila and the other is the Shardana. The Sikila settled north of the Philistines in the middle part of the Canaanite coast. The Shardana were still further north. We have this from Egyptian records, of course. I believe there may be one more tribe of Sea Peoples here—the Danuna or Danaoi, also mentioned in Egyptian sources.

HS: Is there a connection between the Israelite tribe of Dan and the Sea People known as the Danuna?

Moshe: Yes. They meet somewhere on the coast near Jaffa in the area of the territory allotted to the tribe of Dan in the Bible. The two people somehow mix. I don’t know the origin of the tribe of Dan. But the Danuna was an old tribe in the western Mediterranean; afterward they appear in many places. I am sure that some of them somehow mixed with the tribe of Dan.

HS: Do you think that when the Sea People tribe of Danuna settled in Canaan that they then mixed with the Israelites who took the name of Dan from the 046name Danuna? Is that how it worked?

Moshe: We don’t know exactly how it happened, but it is very interesting that the Danuna appear somewhere near Jaffa, precisely where, according to Biblical tradition, the Israelite Danites were supposed to settle.

HS: Were the Israelites already there?

Moshe: This is the question. We still don’t have the evidence that would connect the two. But it is too close for there not to have been some connection. For some reason the Danites left the place allotted to them and then go up to northern Dan. This is told in the Bible.e At the same time we have the Danaoi mentioned in all kinds of sources, including Egyptian sources. I am really following in the footsteps of Yigael Yadin here.

HS: I can understand where the Danuna or Danaoi came from. They were a Greek Aegean element. But what is the Israelite source of the Danites?

Moshe: I don’t know how it was written, what the source of the story is. But suddenly part of the Israelite tribe of Dan leaves its allotted territory and goes north. They may be the Danaoi who were more closely connected with the Israelites. All the other Danaoi stay somehow in Danuna, if you like—that is, in the original tribal allotment of Dan.

HS: How did the element of the Israelites who mixed with the Danaoi get to the area of Jaffa?

Moshe: According to the Bible, they were very near the coast, only a few miles from the coast. Maybe they were in Jaffa under Egyptian rule. The names are so close; but we don’t have the last piece of evidence that ties it all up.

HS: Who was at Dor?

Moshe: The Sikila were at Dor. The Shardana were farther north.

HS: How do you know this?

Moshe: The Egyptians list them in this order.

HS: You assume that the Egyptians put the names in geographical order. The Egyptian records don’t actually say which Sea People are where, do they?

Moshe: No, they don’t say, but it seems so. The Shardana are always in the north because they are always mentioned after the others. The Sikila are mentioned in the Egyptian tale of Wen-Amon as being in Dor.

047

HS: The Wen-Amon story dates from when?

Moshe: We think it dates from the 12th century.

HS: And Wen-Amon speaks of being in Dor and seeing the Sikila in Dor?

Moshe: Yes. The Sikila are the easiest to pinpoint because of the Wen-Amon story.

There is one more element, the Greek Wanax.

Wanax is a kind of king or head of the tribe. It is also a generic name for the king or head of a community or of tribes. It appears in hundreds of ancient Greek inscriptions—in Linear B and later in regular Greek. I believe Wanax is related to the Anakim referred to in the Bible as a people who are in the southern part of Canaan before the Philistines. The trouble is that it is not so easy to transform the Greek omega and make it an ‘ayin in Hebrew in this period. Otherwise I would jump on the connection immediately.

HS: Are you saying the Biblical Anakim may have been one of the Sea Peoples?

Moshe: In the end they were. Originally, they were in the Peloponnese in Greece. I think when the Greek peoples dispersed and went to all kinds of places, part of them came to Canaan. These Greeks were already settled here when the Philistines came. They came a little before the Philistines. In Ashdod, they may be our stratum 13.

HS: Is that the monochrome stratum?

Moshe: Yes.

HS: How do you associate that with the Anakim?

048

Moshe: In the Bible, it says the Anakim were in Ashdod before the Philistines.f

HS: You think there may have been another Sea People here before the Philistines?

Moshe: I don’t say 100 percent, but I think is was something like this. The Anakim were in other places, but Ashdod may have been their most important site.

HS: Why do you think all of these different Sea Peoples, who were really Greeks, as far as we know—their culture is clearly related to the culture found contemporaneously in the Aegean area—why did they all go to Egypt and the eastern Mediterranean littoral?

Moshe: We really don’t know. So many books and so many articles have been written about what really happened in the Peloponnese at this time. But these people started to leave their own country or countries and look for some place else to live. We don’t know why. Perhaps there were wars or maybe famine. The Shardana, for example, gave their name to Sardinia. The Sikila gave their name to Sicily. We know this from later traditions—from the eighth or ninth century B.C.—but, of course it all goes back much earlier.

HS: So they didn’t go only to the eastern Mediterranean?

Moshe: Not at all.

HS: The whole world was in great turmoil at this time. The Hittite empire was collapsing, Egyptian hegemony was losing its hold. Isn’t that correct?

Moshe: Yes. It started at the end of the 13th century [B.C.]. We don’t exactly know when Sardinia and Sicily got their names, but it seems it was quite, quite early. Archaeologists in Sardinia and Sicily are finding evidence of this, but we can’t yet pinpoint the time.

Our most important source, really, is the Egyptians. The Egyptians called them the Sea Peoples. That’s how we got their name. They say they are coming by thousands with enormous troops. Many more nations are mentioned than those we have already referred to, nations that are otherwise completely unknown. No place is given for them, so we don’t know where to look. But this was an enormous movement.

049

HS: Are you saying that there was one cause for all this upheaval all over the Mediterranean?

Moshe: Perhaps there were some inner causes in certain countries. But don’t forget that some enormous towns like Ugarit were destroyed.

HS: That’s in modern-day Syria?

Moshe: Yes, but this destruction occurred all along the Syrian coast, from what is today Turkey.

HS: Isn’t it hard to believe that thousands, or tens of thousands of people, would come out of this turmoil in the Aegean and be able to destroy much of the world?

After all, there were sophisticated civilizations in Egypt and in Ugarit, for example. How could these people destroy these civilizations? It is at least as difficult to imagine such a destruction by the Sea Peoples as to imagine the destruction of Canaanite cities by the Israelites.

Moshe: The Sea Peoples didn’t destroy the Egyptians.

HS: But how could these Sea People come from the Aegean and take over and destabilize other civilizations?

Moshe: They didn’t take over Egypt.

HS: They destroyed Ugarit.

Moshe: Yes.

HS: Let’s take the case of Ugarit. It was a fantastic civilization. And here you have these Sea Peoples who are apparently leaving because of famine or war and yet somehow they were able to organize a military armada on land and sea and fight the Egyptians, even if they lost, and destroy Ugarit. I’d like to know how they did it. And then I’d also like to know, if they could do it, why can’t we as easily imagine the Israelites coming in and successfully fighting the Canaanites. Trude, maybe you could provide part of the answer.

Trude: I don’t know the answer to this. I don’t know how the Sea Peoples did it. It’s one of the cardinal questions. It used to be very clear that the Sea Peoples came and destroyed. That was always the explanation. Now I don’t think it’s so clear. Now the trend is very different. Many scholars are working on the problem—on the end of the Hittite empire in Anatolia, the end of Ugarit, the destruction of cities in Canaan, the end of the Mycenaean palace culture in Greece. They don’t see it anymore as attributable to the 050Sea Peoples. That’s not the main cause. The coming of the Sea Peoples is an outcome. Now, the explanation is more often famine, or drought or things like that.

But of course, this too is an easy way out. You have to be very careful. I don’t think that the Sea Peoples came with an armada and did it all. The situation is different in different places. Ugarit was destroyed. No doubt about it. Egypt is another story. Here there was a very shore interregnum of destabilization between the XIXth and XXth dynasties—only 10 or 15 years. But Egypt was very strong. In Philistia [Canaan], the picture is again different. Here we do have a continuation of a previous culture with the Philistines settling down.

Moshe: But they destroyed it first.

Trude: They destroyed it, but then they settled it. The cities were definitely destroyed.

It’s not a simple picture. These are very complex things. You talk about the end of the Hittite empire. That is another story. The Hittitologists have so many different ideas as to what happened. Cyprus is another story.

HS: Were there destructions on Cyprus?

Trude: Yes, but then there is a 051rebuilding. The 12th century was one of the most flourishing periods in Cyprus. It may have begun in the 13th century, but it definitely comes again from the Aegean world.

We have a very similar phenomenon with the settlement of the Philistines in Canaan.

There is, it is true, an end of a period, the end of maritime trade, the end of the great maritime cultures of the late Bronze Age, the powers of the 14th century and 13th century. In Iron Age I (1200–1000 B.C.), we no longer find a maritime connection between the Greek world and the Orient.

HS: There was a kind of disintegration?

Trude: Definitely.

HS: So you do have a disintegration, for whatever cause, and these Sea Peoples go around the world and in effect take over or insert themselves into other cultures, other civilizations. Its a complex process. In some cases there are destructions.

But if the Sea Peoples are fleeing, if they are running from a difficult situation, they are not in a position to organize. How could they impose themselves on peoples who didn’t want them? How could they conquer the cities that were destroyed? Yet they appear to have done it. Now, what I want to ask you is this: The situation of the Sea Peoples sounds to a lay person a lot like the Biblical description of the conquest of Canaan, where you have these runaway slaves as it were, people who weren’t of high culture, yet who were able to infiltrate and conquer and in some cases, according to the Biblical text dispossess other peoples and to settle there. The descriptions in the Bible are all very realistic in their geopolitical aspects. Militarily the Bible is very careful to describe it in a way that is strategically very clever and makes sense in terms of the topography. There is a tendency to completely reject this in the case of the Biblical Israelites, yet we accept it in the case of the Sea Peoples. And we even say we have archaeological confirmation of this in the case of the Sea Peoples. Can you explain this, Trude?

Trude: Again, you ask a difficult question. I won’t even venture to answer it. I can only say that as an archaeologist, I’m definitely modest about it. I don’t think I can solve all the problems: Why the Hittite empire fell; why there is no continuation there; why there is this dark age; why Ugarit wasn’t rebuilt; et cetera.

The whole Mediterranean was in an upheaval, no doubt about that. There is definitely an end of trade. This is terribly important. Some places recover very quickly, others [do] not. In Canaan, we have the phenomenon you talked about with the Israelites and the Philistines. I think this has to be studied and restudied. It has been done, but we see how different the conclusions are.

You ask how did these Sea Peoples wander in these ships, meandering through the seas. I don’t think those who fled were the lowly people. Whoever managed to go on the ships were not only the sailors, but the elite who brought their culture with them. In Philistia they built large, well organized cities.

HS: Was there a cultural break in Greece itself?

Trude: There you had the culture of the Mycenaean palaces. This ends. But then you have a continuation of life in these palaces. In Tiryns, for example, 052there is a revival, similar to what we have in Philistia. But the social structure is then very different in Greece. No longer is there a Wanax or king. It’s a different social set-up.

HS: Do we have any idea what caused the upheaval in Greece?

Trude: Well, it needn’t be the coming of the barbarians or the Dorians, as used to be said. So now we can say that it’s the result of social change. Or you can speak about drought, or about climatic change or wars. Again, it’s the same question.

This is something that is very hard to answer archaeologically. Something happened. But interpretations of what happened will be very different. On the other hand, archaeology can show that there is a new barbarian pottery in Greece.

Earlier you asked if archaeology is the handmaiden of history. I think we really need to take historians and linguists and archaeologists and sociologists and people who can talk about drought and climates—and all work together. In a way, this is what it is all about. We have to have this interdisciplinary approach.

HS: One thing seems clear in Philistia, that there was a monochrome phase in the pottery and then a bichrome phase. Am I correct?

Trude: Yes.

HS: Moshe associates the monochrome, the earlier phase, with the Anakim?

Moshe: It’s a suggestion.

HS: Is this monochrome phase at all Sea People sites?

Moshe: This monochrome phase appears in all sites that are being or have been excavated with modern methods. We don’t know about sites excavated 100 years ago. We don’t have enough evidence.

HS: If the monochrome phase appears in all these sites preceding the bichrome phase, Moshe, do you associate the monochrome phase with an earlier Sea People before the Philistines at all these sites?

Moshe: This is my suggestion. But it doesn’t have to be the same at all sites. In the Bible, it says that there were people called Anakim in Ashdod and afterwards we have only Philistines in Ashdod. I think that I have the right at least to suggest it.

The Bible says there was an earlier people in Ashdod. In the Biblical period—the 13th, 12th century or 11th century—people knew about it. Perhaps they even saw it with their own eyes. So, if we find, as we do at Ashdod, one early group with monochrome pottery, and a second group with bichrome pottery and with a different town plan, I would say that we have to correlate this with the Bible and conclude that the monochrome is connected with the first people mentioned in the Bible, the Anakim, and the bichrome ware is connected with the second people, the Philistines.

HS: How do you explain the elimination of the Anakim?

Moshe: They were just assimilated because they were cousins of the Philistines.

HS: So the Philistines are a little like the Russian immigrants who are now coming to Israel?

Moshe: Exactly. The name Wanax is not completely the same as Anakim but I do have good evidence of the relation from my friend, Mrs. [Anna] Morpugo [Davies, of Somerville College, Oxford]. She is the best in this pre-Greek grammar and philology. She says it is 50 percent.

HS: What is your view of this problem, Trude?

Trude: First of all, what Moshe said relates to Ashdod. The only city of the Philistine pentapolis that the Bible says has Anakim is Ashdod. It’s an idea, but it has to be proven. It’s a philological problem connected to archaeology, so it’s very legitimate. On the other hand, there are differences in the cities of the pentapolis. For me, it is not important. It’s one group of the Sea Peoples. I can call them early Philistines. For me, the first phase of settlement, the monochrome phase, is the Philistines—in Ekron, in Ashdod and in Ashkelon. It’s definitely part of the same picture. And it will be the same if these are the Wanax, or Aegean or Achaean or whatever. But I don’t go as far as that yet.

053

HS: I’d like to ask you about the relationship between the Philistines and the Israelites. In a site like Lachish, which is perhaps 20 miles away from Philistia or less, you don’t find any Philistine ware. What does this tell us about the relationship between the Philistines and the Israelites?

Trude: [Laughter.] This is a discussion that David Ussishkin [the excavator of Lachish] and I always have. First of all, there are a few Philistine sherds from Lachish. Second, Lachish was not settled at that time. There was a gap after Ramesses III.

HS: So you do think that when there was simultaneous settlement there would be trade?

Trude: Yes, definitely. But Lachish has this gap in settlement. This we know. Between stratum 6 and stratum 5 something happened. The second half of the 12th century is not there. The 11th century is problematic.

HS: What does archaeology tell us about relations between the Philistines and Israelites?

Trude: In the early periods?

HS: Yes, in this monochrome and bichrome period of the Philistines. Are there Israelite sites where we find some evidence of relations with the Philistines?

What about the small settlements in the central hill country that are supposedly Israelite? We have no Philistine pottery there, do we?

Trude: A sherd was found at Izbet Sarteh. I believe.

HS: Can we conclude that in this early period, the Israelites and the Philistines led lives very isolated from one another?

Moshe: There were not too many Israelites living in the southern part of the country. This is where the Philistines were strong.

HS: We know where the Philistines were strong. We know where the Israelites were living. What I am asking is whether there was any relationship, commercial or otherwise, between the two peoples.

Moshe: Very little. There was perhaps a kind of coexistence at a place like Afula, near Megiddo, where I found both Israelite and Philistine pottery. So there was some coexistence. It could happen.

HS: But not in the central hill country. I don’t know of a single Philistine sherd found in the hill country. Do you, Trude?

Trude: No. You asked the right question. But I think one has to look at the quantities—not one sherd or two, here or there. Dan, incidentally, has some very interesting Philistine pottery. So should we connect this with the Danuna?

HS: In Philistia or in the areas settled by the Sea Peoples, do we have any indication that the Israelites traded with them? For example, do we find any collar-rim jars at Sea Peoples sites?

Moshe: Never along the coast.

HS: So it seems from the archaeological evidence from the early period, the Israelites and the Philistines were very isolated from one another?

Moshe: Apart, yes.

Trude: In the initial phase, yes. But by now everybody more or less agrees that the collar-rim jar is not the hallmark of the Israelites. It is found so widely that we have to be very careful about that.

HS: Isn’t it true that most of the collar-rim jars—the heaviest concentration of them—are found in the area that the Bible ascribes to the Israelites?

088

Trude: Yes it is, but it is also found quite widely elsewhere.

Moshe: The collar-rim jar was needed more in the hills for water.

HS: Are you saying the collar-rim jar cannot be used as an element in identifying the site as Israelite?

Moshe: It may help but its presence is due mainly to the economic factor. In the hill country, they needed it. But if some non-Israelite tribe lived in the hill country they would also be using it.

HS: We have established that there is very little evidence of Philistine culture or trade coming into the areas that were occupied by the Israelites. Can we also say that there is very little from the Israelites coming into the Philistine areas at this early stage?

Moshe: I would say extremely little.

HS: Moshe, we haven’t found a Philistine archive yet, but what little writing that has been found at a Philistine site was found by you at Ashdod. Is that correct?

Moshe: I have two pieces but they are not yet read. Somebody in the United States tried.

HS: Who was that?

Moshe: Robert Stieglitz. He’s not sure of his reading.g I am even less sure of his reading.

HS: So, we haven’t really found any Philistine writing yet?

Moshe: No. Not from the early period. Later they probably used the Hebrew or Phoenician alphabet, but nothing earlier than the eighth century B.C.

HS: What do you think about the Philistine control of metal in early Israelite times? Did they really have this monopoly on metal, and was this the reason that they were such a threat to the Israelites?h

Trude: This has been a kind of myth, one of those holy cows. It’s supposedly based on the Bible.i But in the Bible you don’t have the word “iron.” The Hebrew word is barzel. Jane Waldbaum has shown very beautifully that barzel is not iron.j The Philistines had a monopoly on metal working but not on iron. The Philistines brought with them the knowledge of how to work iron. That is what the Biblical sentence is referring to, but iron is not mentioned. Only metal working is mentioned.

At Ekron, we have found a large number of iron objects. But they are mostly elite, artistic objects—knives with ivory handles found in the shrine on the bamah [offering platform]. In the initial phase of Philistine settlement at Ekron, iron objects were found near a decapitated puppy burial. But iron is not yet part of everyday usage in the 12th and 11th century B.C. The same kind of iron knives were found in the Philistine temple at Tell Qasile. They have parallels in Cyprus and Greece. But it’s not yet in everyday life. It’s not like the tenth or ninth or seventh century when you have iron plows and things like that. Earlier iron was used for religious objects, like these ivory knives found on the bamah.

HS: Toward the late 11th century a clear conflict developed between the Israelites and the Philistines. There was an important battle somewhere between Aphek and Ebenezer.

Trude: Yes.

HS: The Israelites lost the battle. The ark was captured by the Philistines. Did the Philistine expertise in metal working play any part in that battle?

Trude: I don’t think that archaeology can answer that, but we can say that these Philistine cities were strong. But we haven’t found the tombs of the warriors. Emily Vermoule [professor of classics at Harvard University] asked me, “Where are the tombs of the heroes?” That’s where the fantastic finds would be, if there are any—in the burials. We haven’t found them—not in Ashdod or Ashkelon or at Ekron. This makes it a little difficult to give a complete picture. But we know the organization of the city plans, we know the buildings, we know that economically they were flourishing. So the military force must have been elite. But we haven’t found any weapons at Ekron or at Ashkelon. It would be nice to find them.

HS: Do either of you want to add anything that I haven’t asked about?

Moshe: As time goes on, we see that more and more of the facts mentioned in the Bible can he used in reconstructing what we find in our excavations. The truth is that everybody, even people who are against the Bible, go first to the Bible to see if something there supports what they find. Many Biblical texts have been vindicated. When the Bible gives us a sentence or even a word, we have to use it.

HS: Trude, do you want to add anything?

Trude: I am an archaeologist, a dirt archaeologist. But without having a framework I would just have to call what I find a pot. It would be anonymous. I think we are very fortunate that we have these Biblical records, but we take them cautiously. We don’t go with the Bible in one hand and the spade in the other, but it definitely must be used.

Why is this country so important archaeologically? It’s not because we have such grandiose finds. It’s important only because it speaks to us. It’s part of our heritage. It feels great that you can, in a way, read about your finds in the Bible. If you find an inscription, it talks to you straight. It bridges the centuries. I think that this is really a great feeling, but you have to do it cautiously. You can’t go about it blindly. I’m not a Biblical scholar. I am a plain archaeologist. I try to use all the sources available and go to the people who know more about these things for help. And then I try to integrate it all.

HS: Thank you both very much.

In our previous issue (“The Philistines and the Dothans—An Archaeological Romance, Part 1,” BAR 19:04), archaeologists Moshe and Trude Dothan spoke with Hershel Shanks about their early years together, as were embarking on careers in archaeology and at the same time beginning a family They shared their impressions of the great women and men they knew who pact their stamp on archaeology in Israel. In this concluding installment, the Dothans talk in depth about their own research, focusing in particular on the legacy of the Philistines and other Sea Peoples. 041 Hershel Shanks: If you two had a nickname, […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Footnotes

Trude Dothan and Moshe Dothan, People of the Sea (New York Macmillan, 1992). See review by Jane Waldbaum in Books in Brief, BAR 19:03, and

For more on Ekron, see Trude Dothan and Seymour Gitin,“Ekron of the Philistines,” BAR 16:01 and “Part II,” BAR 16:02. For the Philistines in general see Trude Dothan, “What We Know About the Philistines,” BAR 08:04.

For more on Ashkelon, see Lawrence E. Stager, “When Canaanites and Philistines Ruled Ashkelon,” BAR 17:02; “Why were Hundreds of Dogs Buried at Ashkelon?” BAR 17:03 and “Eroticism and Infanticide at Ashkelon,” BAR 17:04.

See Bryant G. Wood, “The Philistines Enter Canaan: Were They Egyptian Lackeys or Invading Conquerors?” BAR 17:06; and Itamar Singer, “How Did the Philistines Enter Canaan? A Rejoinder,” BAR 18:06.

“And six hundred men of the tribe of Dan, armed with weapons of war set forth from Zorah and Eshtaol, and went up and encamped at Kiriathjearim in Judah . … the Danites came to Laish, to a people quiet and unsuspecting, and smote them with the edge of the sword, and burned the city with fire. And there was no deliverer because it was far from Sidon, and they had no dealings with any one … And they rebuilt the city, and dwelt in it. And they named the City Dan, after the name of Dan their ancestor” (Judges 18:11–12, 27–29).

“And Joshua came at that time, and wiped out the A’lakim from the hill country, from Hebron, from Debir, Eom Anab, and from all the hill country of Judah, and from all the hill country of Israel; Joshua utterly destroyed them with their cities. There was none of the Anakim left in the land of the people of Israel; only in Gaza, in Gath and in Ashdod, did some remain” (Joshua 11:21–22).

See James D. Muhly, “How Iron Technology Changed the Ancient World and Gave the Philistines a Military Edge,” BAR 08:06.

Now there was no smith to be found throughout all the land of Israel; for the Philistines said, ‘Lest the Hebrews make themselves swords or spears’; but every one of the Israelites went down to the Philistines to sharpen his plowshare, his mattock, his axe or his sickle; and the charge was a pim for the plowshares and for the mattocks, and a third of a shekel for sharpening the axes and for setting the goads” (I Samuel 13:19–21).