The Saga of the Goliath Family—As Revealed in Their Newly Discovered 2,000-Year-Old Tomb

044

In the mid-1970s, a number of limestone ossuariesa came onto the Israeli antiquities market, the result of illegal digging. An investigation conducted by the Israel Department of Antiquities located the source of the ossuaries in the Jericho hills, and prompted an emergency salvage excavation. That excavation, led by Rachel Hachlili, uncovered a Jewish cemetery more than seven miles long. This mammoth cemetery spans seven Jericho hills and includes approximately 120 excavated and surveyed tomb-caves. The tombs encompass a 150-year period that ended when the Romans destroyed Jericho in 68 A.D. in their campaign to crush the First Jewish Revolt.

The general features of the cemetery have already been described for BAR readers (“Ancient Burial Customs Preserved in Jericho Hills,” BAR 05:04). This article will focus on one tomb, the largest and most monumental in the cemetery, and on the obviously prominent family buried there. The article will also describe how modern computer technology enhanced discoveries about the people buried in this Jericho cemetery 2,000 years ago.

We were initially led to this particular tomb by the outline of four low walls forming a square 42.7 feet × 42.7 feet which still protruded above the surface. Although the outline of these walls might have gone unnoticed by the casual visitor, to the practiced eye of an archaeologist, it was obvious that more lay beneath the surface.

When we excavated and cleared part of the area enclosed by the wall, we found plastered “benches,” forming three steps 4.3 feet high along the inside of three of the walls. We were obviously inside some kind of courtyard.

Outside the courtyard, on the north, we found a ritual 046bath or mikveh in which purification rites probably took place. The mikveh consisted of two pools. The upper pool, measuring 7.9 feet × 5.6 feet and 5.9 feet deep, served as the holding pool for pure spring or rain water which in this case was brought to it from an aqueduct. The second pool, measuring 10.8 feet × 8.5 feet and 6.6 feet deep, had five steps leading down to its base and served as the actual bathing or immersion pool. Before the lower pool could be used, the connecting pipe between the two pools would be opened to allow some of the stored rain water to flow into the bathing pool. Thus the pure water from the holding pool would purify the immersion pool.

047

The fourth wall of the courtyard—the western wall—was the one that particularly attracted our attention. It had no bench on the inside. When we excavated the two ends of the wall it became obvious that these two ends did not align; they would not meet in the middle. At the end of the season, the middle section of this wall remained unexcavated. We would have to wait until the following season to solve the puzzle.

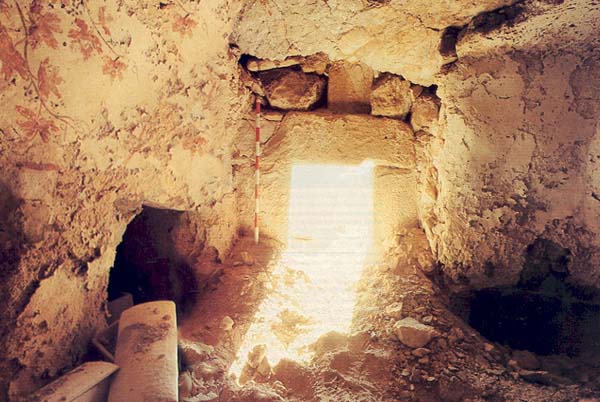

The first thing we did on returning to the site was to excavate the remaining section of the fourth wall of the courtyard. Indeed, the ends of the wall did not meet. In the center was a passageway which we followed, first removing enormous quantities of earth. Gradually we were led inside the adjacent hill. Architectural fragments that may have belonged to a monumental entrance to the tomb were found in the fill as we dug our way through the passage into the hill. Finally, on the last day planned for the season we came to the outline of a large tomb. We promptly decided to extend the season. It was clear that we had found an unusually important tomb. The courtyard we had previously excavated was probably the place where mourners gathered to grieve, or to remember their loved ones. The mikveh was probably connected with purification rites of the mourners when they entered or left the tomb area—or perhaps both on entering and on leaving. The entrance itself had been carved from the rock and then ashlar blocks had been added on the sides and top to form the rectangular entrance.

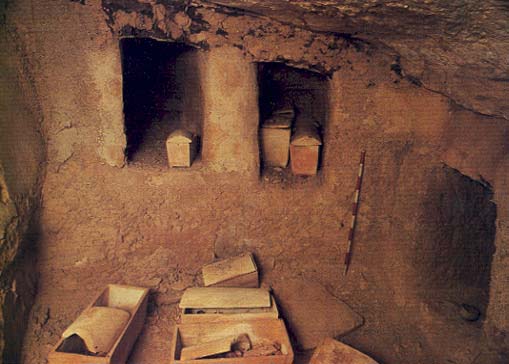

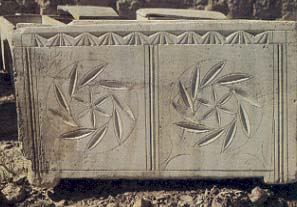

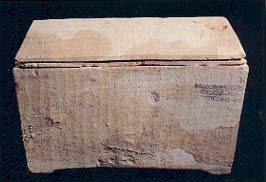

We entered a large rectangular chamber similar in plan to other tombs in the cemetery and typical of the period; but this chamber was by far the largest yet found in this enormous cemetery. The main chamber, measuring 11.5 feet × 8.2 feet, had a central pit, eight loculib and a repository pit to the left of the entrance filled with approximately 100 skeletons gathered into piles. Ossuaries were dispersed mainly on the north side of the tomb, two in each of the northern loculi, three in front of them and one in the passage. A lid of one of the ossuaries found in the pit was inscribed in charcoal with the first nine letters of the Greek alphabet. The inscribed lid was evidently placed in the pit, with the inscription facing the entrance for all visitors to the tomb to see. What was the purpose of this inscription? It may have had some “magical” or “symbolic” meaning, perhaps to frighten evil spirits.

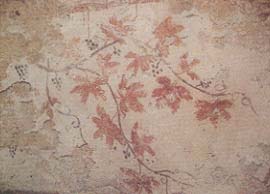

Not only was the chamber larger than any other in the cemetery, it was also uniquely decorated. The walls had been plastered and then adorned with a brightly colored fresco, executed in red, brown, and black and depicting vines with trellises, leaves and ripe grapes. Birds were perched on the branches of the vines. On the wall opposite the entrance was a painted wreath and several blocks of painted masonry. Unfortunately the fresco on this wall was very poorly preserved. The arches of the burial niches were also decorated, in red and black stripes.

On the north wall of this rock-hewn chamber—on our right as we entered—we found the entrance to a short passageway consisting of three steps which led down to a second chamber only slightly smaller than the first. Although its walls had been plastered, they had not been decorated with frescoes as had those of the first chamber. As we shall see, the remains of some of the most important family members were interred in this lower tomb chamber. The second chamber, measuring 9.8 × 9.8 feet, had six burial niches or loculi so that altogether there were 14 loculi in both chambers. In all, we found 22 048ossuaries in the two chambers and the passage in between. Some of the ossuaries were in loculi. Others, obviously disturbed, were strewn about the two tomb chambers.

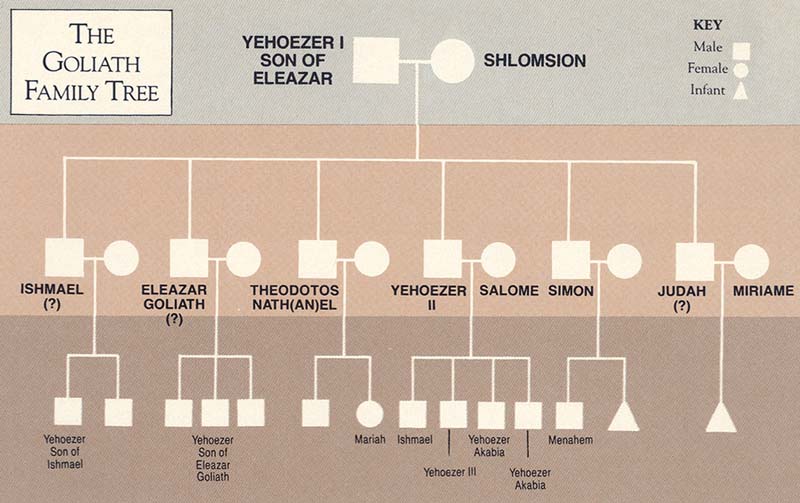

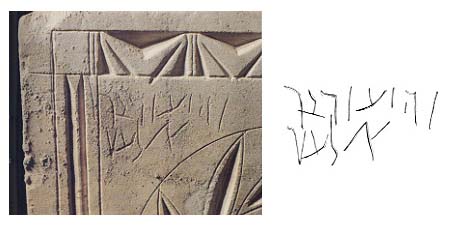

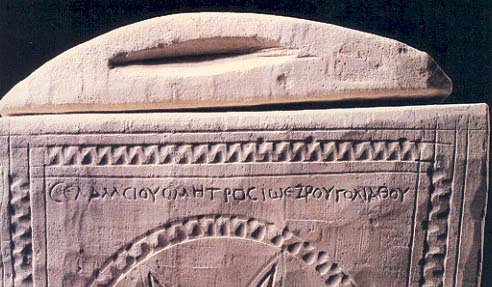

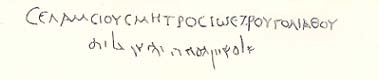

We found 32 different inscriptions on the ossuaries, 17 in Greek and 15 in the Aramaic language, the latter written in what is known as Jewish or square script, the same script in which Hebrew is written today. The inscriptions generally give the name of the deceased and a family relationship like “Miriame wife of Judah.” Sometimes we are told a bit more. All but one of the names are Jewish names, but they are frequently transliterated into Greek letters. Indeed the presence of so many Greek inscriptions reflects the importance of Greek vis-a-vis Aramaic in Judea at this time. Obviously, this family was not only literate, but bilingual.

Most of the inscriptions are incised into the soft limestone with a chisel or nail, but an occasional inscription is executed in ink or charcoal. Inside the 22 ossuaries we found the remains of 32 different people. Some ossuaries contained the bones of two individuals and, on occasion, three. From the inscriptions we were able to construct a family tree of three generations interred in the cemetery.

In order to check the validity of our conclusions statistically, we turned to the computer. The computer study, done by Mori Rimon of IBM, Israel, began when we first fed the information contained in the inscriptions—the names and the various relationships—into the computer. Unfortunately (for this purpose) a number of names are repeated several times (seven family members used the name Yehoezer) and overall there are more individuals than names, so some of the individuals must forever be unnamed.

Next, we fed the computer the results of our osteological studies. Our anatomy expert (Professor Patricia Smith of Hebrew University and Hadassah Medical School) was able to tell us whether each set of ossuary bones belonged to a male or female and at approximately what age each had died.c

Certain logical deductions were then given to the computer. Five people died before their first birthday; six more died before they were 13 years old. Obviously, none were parents. If two males were buried together, obviously they could not be husband and wife.

Next, certain assumptions were made: If two males were buried together, this supports the hypothesis that they were father and son. Other assumptions were made based on the location of ossuaries.

049

Finally, each individual was assigned a numeric vector derived from 13 different details which would help the computer determine the family tree.

All this may sound complicated, but in fact it is far more complicated than it sounds. In the end, however, the computer confirmed the family tree we had constructed based on the inscriptions, and we were able to place 28 of the 32 people on the family tree (although some of the individuals only had numbers, but no names). Some of the relationships were less certain than others, so we divided the relationships into those that were certain and those that were only probable. The result is the family tree below.

We have called this family the Goliath family, although people did not have family names in those days. People were known simply as A the son of B, C the wife of D, or E the daughter of F.

However, people did have nicknames or appellatives. For example, Josephus, the first-century Jewish historian, refers to two of his forebears as “Simon the Stammerer” and “Mathias the humpback.”1 An ossuary was found in Jerusalem which was inscribed “Yehuda the scribe.”d And another Jerusalem ossuary inscription refers to Yehonatan the Nazarite.e

Three of the people whose names are inscribed on our ossuaries bore the appellative “Goliath.” Indeed, the name Goliath appears five times on the ossuary inscriptions, both in Jewish and Greek script, always added to the name of an individual. Goliath was of course an enemy of Israel, the Philistine giant whom young David slew with his slingshot (1 Samuel 17). It is unusual for a Jewish family to bear the name of one of Israel’s enemies, but the key here probably lies in the fact that the members of this family were so tall. Thus the nickname Goliath was attached to successive generations of this Jericho family.

050

Our osteological studies identified four male members of the family who were exceptionally tall for their time. Based on the size of his long bones, the man identified as Yehoezer, son of Eleazar, was indeed a Goliath of a man—over 6 feet 1 inch tall at a time when the average height of a full-grown man was about 5 feet 5 inches.

This “Yehoezer son of Eleazar” was the father of the clan. Because the name Yehoezer is repeated on the ossuaries for seven different people, we shall refer to this Yehoezer as Yehoezer the First. The bones of Yehoezer the First were contained in an inscribed ossuary from the lower chamber of the tomb. Three other ossuaries were found in the same loculus with this ossuary. Together these four ossuaries bore inscriptions which provided the most important information about the main trunk of the family.

“Yehoezer son of Eleazar”—Yehoezer the First—died when he was about 30 years old, as we learned from a study of his bones. The tomb was probably first hewn for this patriarch. His wife Shlomsion was buried next to him. She died in her sixties, thus outliving her husband by at least a quarter of a century.

One of the other ossuaries in this loculus contained the remains of Yehoezer the First’s and Shlomsion’s eldest son, whose ossuary inscription identified him as “Yehoezer son of Yehoezer Goliath.” Thus the son’s ossuary identified the father as Yehoezer Goliath (the First). This inscription establishes the father’s nickname. The father’s own ossuary described him simply as the son of Eleazar, without any nickname. The final ossuary in this loculus contained the bones of Yehoezer Goliath the Second’s wife, Salome. Salome’s ossuary also contained the bones of the couple’s two children, Yehoezer (the third generation to bear this name) and Ishmael.

Thus in this single loculus we found the bones of three generations of the family. The other 16 ossuaries found in the tomb contained the bones of other sons of Shlomsion and Yehoezer the First, wives of these sons, and the sons’ children.

Two small ossuaries nearby contained the bones of two children probably born to Salome and Yehoezer the Second. One of the children was an infant, only about six months old when he died. The other was between three and four years old. Both children’s ossuaries bore the same name, “Yehoezer Akabia.” Two children in one family bearing the same name is an unusual occurrence indeed. After the first child died, his parents probably decided to name the next male in his memory.

It is also remarkable that these children had double names—Yehoezer Akabia. In neither case does a ben (son of) appear between the two names. For some reason these children were given two names. It is the only occurrence in ossuary inscriptions of this phenomenon. A glance at the family tree may provide the answer to this puzzle. By the third generation there were at least three additional Yehoezers in the Goliath family and the addition of Akabia after Yehoezer was simply a necessary way of distinguishing among all the Yehoezers.

Yehoezer the First and Shlomsion had at least four and perhaps five additional sons who were buried in the tomb. The tomb also contained the bones of the sons’ wives and their children.

Yehoezer and Shlomsion probably also had daughters, but they, presumably, were buried in the tombs of their husbands. Upon marriage, a woman was considered a member of her husband’s family.

Shlomsion’s ossuary is inscribed “Shlomsion mother of Yehoezer Goliath.” Just as we learned from the second generation Yehoezer that his father was called Yehoezer 052Goliath, so we learn from Shlomsion’s ossuary that the second generation Yehoezer also bore the nickname Goliath. The inscription on Shlomsion’s ossuary is unusual in that it identifies her as the mother of someone instead of the wife of someone. No doubt this is because her husband Yehoezer the First died at a relatively early age and she was left to raise the children.

The ossuary of one of Shlomsion’s granddaughters was inscribed “Mariah daughter of Nathanel, daughter of Shlomsion.” (In this inscription, the Hebrew word bat meaning “daughter” probably implies “granddaughter.”) Mariah died at about the age of 40. We can assume that she never married because she is identified as the “daughter of … ” rather than the “wife of … ” and she is buried in her family’s tomb. In the inscription, Mariah is identified as the granddaughter of Shlomsion instead of the granddaughter of Yehoezer the First, again reflecting the importance of Shlomsion who, as a widow for approximately 25 years, must have been the ruling matriarch of the family.

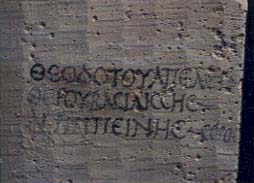

No ossuary was inscribed with the name of Mariah’s father, Nathanel. But there was an ossuary inscribed with the name Theodotus, who is almost surely Mariah’s father Nathanel. Theodotus means “Given of God” in Greek. And that is what Nathanel means in Hebrew. Theodotus is simply the Greek translation of the Hebrew name Nathanel and is the only non-Jewish name inscribed on the ossuaries.

The inscription on Nathanel/Theodotus’s ossuary is interesting for other reasons. In full it reads “Theodotus, a freedman of Queen Agrippina—ossuary.” Queen Agrippina is a well-known historical figure; she was the second wife of the Roman Emperor Claudius and reigned by his side from 50 A.D. to 54 A.D.

Theodotus had evidently been a slave connected with the Roman royal family and had possibly served in Rome itself. As was customary for individuals enslaved by the Romans, Nathanel adopted the name Theodotus, the Greek translation of his Hebrew name. The inscription does not tell us the length of time Theodotus was enslaved; however, we can assume that he was freed between the years 50–54 A.D., during Queen Agrippina’s reign. Queen Agrippina is known to have had close contacts with the Jewish community, particularly with King Agrippa II (53–100 A.D.); this may explain her manumission of Theodotus/Nathanel.

With his freedom, Theodotus automatically obtained Roman citizenship and assumed the special status reserved for those who had served as slaves to the imperial Augustae. Theodotus is thus identified on his ossuary as the “Freedman of Queen Agrippina” because it was something of which to be proud. Probably born Nathanel, he returned to Jericho as Theodotus, Roman citizen and Freedman of Queen Agrippina. There he was buried in his father’s tomb.

Although we cannot be sure, we strongly suspect that the Goliath family was a priestly family. The Talmudf tells us (B.T. Ta’anith 27a) that “24 divisions of priests were in the Land of Israel and 12 of them were in Jericho.” In 053comparison with the other tombs in the cemetery, the monumental nature of this tomb—its two large chambers, the delicate frescoes on the walls of the upper chamber, the courtyard in front—suggests that this was a priestly family. Moreover, the mikveh adjacent to the tomb suggests that the family was priestly and perhaps required purification after a visit involving contact with the dead.

The use of the same name, Yehoezer, in three successive generations, may also indicate a priestly family. The custom of naming a son after a living father was not common among Jews. Originally a foreign custom, it was adopted by the Jewish royal dynasties of the Hellenistic-Roman period (second-first centuries B.C.) and then became prevalent among the Jewish aristocracy and priesthood.

Finally, although most of the names of the family members are common during this period, some, like Eleazar, were used mainly by priests.

We can deduce that the Goliath family used this tomb during the first century A.D. These dates are supported by the reference to Queen Agrippina, the paleography of the inscriptions, the pottery and other small finds. The cemetery was probably not used after the Romans conquered Jericho in 68 A.D.

With the help of computer technology, we have learned a great deal about one family who lived 2,000 years ago. A family with a strong matriarch and unusually tall men, the Goliaths were literate and perhaps priestly. This magnificent tomb has thus provided extraordinary insights into the cultural environment and personal lives of three generations of one Jericho family.

We would like to acknowledge our debt to Mr. M. Rimon of IBM (Israel) for undertaking the design and execution of the computer program and to Professor P. Smith of the Department of Anthropology and Anatomy, Hebrew University and Professor B. Arensburg, Department of Anthropology, Tel Aviv University for their study of the bones in the ossuaries and tomb. The importance of such interdisciplinary cooperation cannot be over emphasized in assessing the far-reaching results of our excavation.

(For further details see Rachel Hachlili: “The Goliath Family in Jericho: Funerary Inscriptions from a First-Century A.D. Jewish Monumental Tomb,” p. 31 ff.; Rachel Hachlili and Patricia Smith: “The Genealogy of the Goliath Family,” p. 67 ff.; M. Rimon: Appendix: “Design of a Computer Program, Establishing the Family Relations of Individuals Buried in the Jericho Tomb,” p. 71ff., all from Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, Number 235, Summer 1979. The excavation of this particular tomb was conducted jointly with Dr. Ehud Netzer of the Institute of Archaeology, Hebrew University of Jerusalem.)

In the mid-1970s, a number of limestone ossuariesa came onto the Israeli antiquities market, the result of illegal digging. An investigation conducted by the Israel Department of Antiquities located the source of the ossuaries in the Jericho hills, and prompted an emergency salvage excavation. That excavation, led by Rachel Hachlili, uncovered a Jewish cemetery more than seven miles long. This mammoth cemetery spans seven Jericho hills and includes approximately 120 excavated and surveyed tomb-caves. The tombs encompass a 150-year period that ended when the Romans destroyed Jericho in 68 A.D. in their campaign to crush the First Jewish Revolt. […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Footnotes

An ossuary is a rectangular box with lid, usually hewn out of limestone and measuring about 20 in. long × 10 in. wide × 12 in. high, which was used as a depository for the secondary burial of the deceased’s bones.

A loculus (plural loculi; kochim in Hebrew) is a burial recess approximately six feet long hewn into a tomb chamber’s wall.

Another study, by Patricia Smith and Baruch Arensburg (“Life Expectancy in Jews Living in Israel at the Time of the Second Temple”), compared life spans and illness patterns of the people buried in the Jericho tomb with their contemporaries in the Mediterranean area. Smith and Arensburg conclude that this Jericho family had a substantially higher percentage of adults over 50 years old (23%) than families in other communities where bones have been studied in Jerusalem, in the Galilee and in Classical Greece. The dry, hot Jericho climate apparently provided a healthy place to live. In the Galilee and Jerusalem, most adult skeletons showed arthritic lesions at the joints. This was rare at Jericho. Rheumatic and respiratory diseases were also far less common at Jericho than at sites with cold, wet winters.

J. B. Frey, Corpus Inscriptionum Iudaicarum, vol. 2, Roma Pontifico Istituto di Archeologia Cristiana, 1952, p. 289 nos. 1308 a–b.

Nahman Avigad, “The Burial-Vault of a Nazarite Family on Mount Scopus,” Israel Exploration Journal 21 (1971), pp. 185–200.