The Aleppo Codex, the most revered copy of the Hebrew Bible, survived intact for more than a millennium before it was ripped apart, burnt, stolen, secreted and, finally, rescued.

On November 29, 1947, the very day that Hebrew University Professor E.L. Sukenik acquired the first three Dead Sea Scrolls and brought them back to Jerusalem, the United Nations passed by a two -thirds vote the resolution partitioning Palestine, effectively creating a Jewish state for the first time in two millennia. To Sukenik, it was almost as if the apocalypse had arrived: A 2,000-year-old Isaiah scroll—which prophesied the return of Israel—surfaced virtually on the same day that Jewish sovereignty was reestablished in the Holy Land.

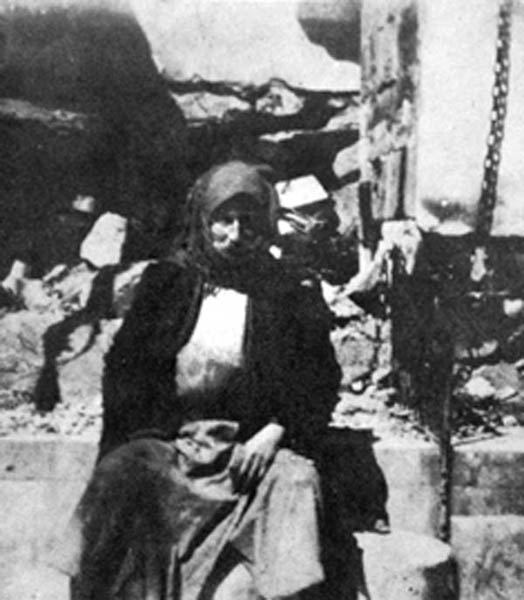

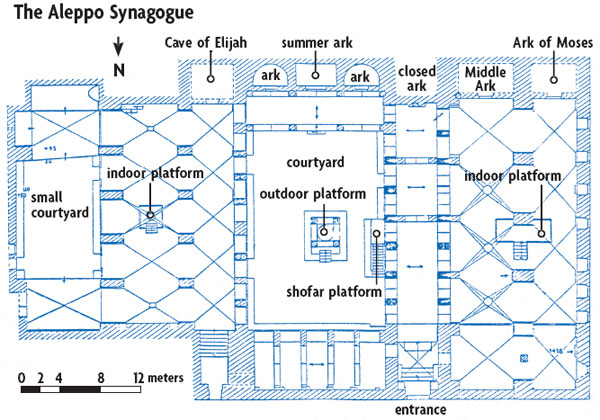

But within two days of that glorious day in Jewish history, disaster struck. In response to the partition vote, anti-Jewish riots broke out in Aleppo, Syria, and elsewhere in the Arab world. The Aleppo synagogues were stormed and their Torah scrolls set ablaze. The worst-case scenario was realized: The Aleppo Codex, the cherished 1,000-year-old manuscript known as “the Crown,” was trashed. Rioters rushed into the Great Synagogue and broke into the locked iron chest where the codex was kept. Precisely what the mob did with it is uncertain; no Jew witnessed it. Fearing for their lives, the Jewish population had barricaded themselves in their homes. The first person to enter the synagogue after the riots was the caretaker (shamash), Shaul Baghdadi. Baghdadi’s son Asher recalled going in and finding his father: “I remember everything. I saw my father weeping like a child … My father sat. And I went through the papers, the piles, to find the pieces of the codex.”

The nearly 200 Biblical texts among the Dead Sea Scrolls are a thousand years older than the Aleppo Codex. But they often vary from one another. The Aleppo Codex on the other hand, is the textus receptus of the Bible. It contains the version that was ultimately selected and accepted as the most authoritative text in Judaism.

Moreover, the Dead Sea Scrolls are written in the style of ancient (and modern) Hebrew—largely without vowels. (Three letters—yod, heh and vav—are used as both consonants and vowels, which is why scholars call them matres lectionis—mothers of reading.) Even if there is no question regarding the letters of a given text, there still may be a question as to how a particular word should be pronounced and what it means.

The Dead Sea Scroll Biblical texts are deficient in other respects. They contain no discussion of various textual problems and their solution. And they contain no indication as to how the Torah portions and the prophetic readings should be chanted in the synagogue.

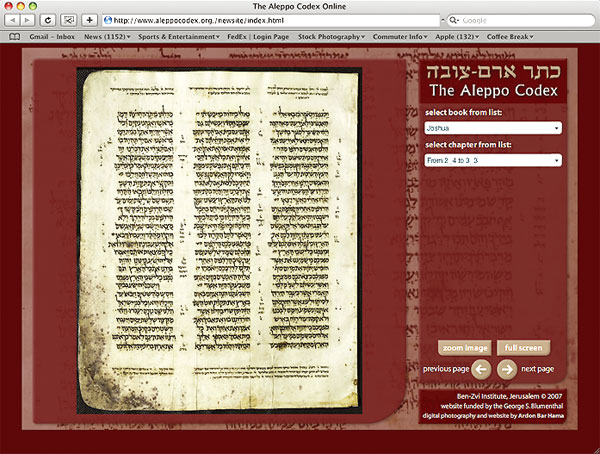

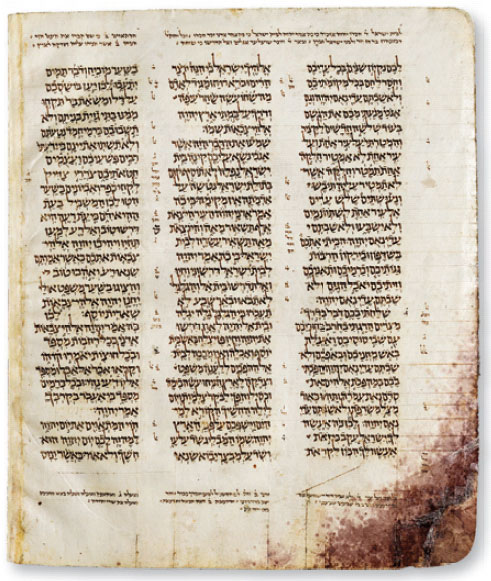

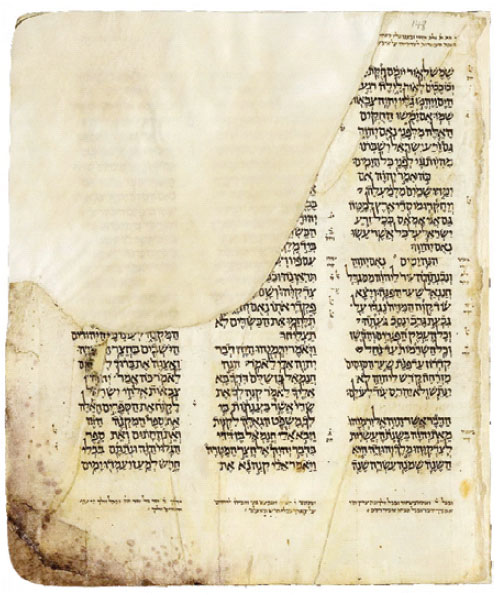

All this is dealt with, however, in the Aleppo Codex. It contains vowel markings (nekkudot) in the form of subscripts and superscripts. It contains other markings (te’amim) indicating pitch relationships (neumes or pneumes, in Greek) to guide the cantor in chanting the prescribed Torah or prophetic (haftara) portion. And it contains massive marginal notations (masora) concerning cruxes in the text.

There is one other important difference between the Aleppo Codex and the Biblical scrolls among the Dead Sea Scrolls: A codex is a book with pages bound together and written on both sides. The Dead Sea Scrolls come from a time before there were codices. The Dead Sea Scrolls were all created as rolls wound around staves. Copies of the Torah used for synagogue readings still follow this ancient tradition. The Torah from which the weekly portion is read in the synagogue must be a scroll, not a codex. Paradoxically, the Aleppo Codex—the most authoritative copy of the Hebrew Bible—cannot be used by the synagogue reader chanting the Torah portion!

The men who created codices like the Aleppo Codex are called Masoretes, after the scholarly notations they made in the margins of the text (masora, literally “tradition”). The Aleppo Codex was created in about 930 C.E. in Tiberias on the Sea of Galilee, the center of Masoretic activity at the turn of the millennium. The Biblical text was written in a magnificent script by a scribe named Shlomo Ben Boya’a. The Masorete Aharon Ben Asher added the voweling and cantillation marks as well as the Masoretic notes written in the margins of the text. Because of his work on the codex, Aharon Ben Asher became, in the words of Professor Menachem Cohen of Bar-Ilan University, “The ideal representative of the Masoretic tradition … [The Aleppo Codex] is indeed of unparalleled proficiency and expertise.” Although Aharon Ben Asher was not the only Masorete, nor even the first, he was the most expert, the Master.

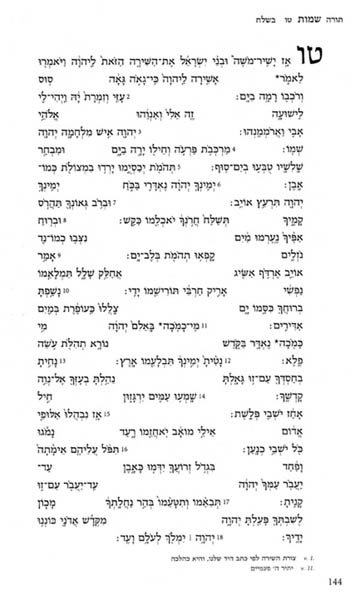

The greatest medieval authority on Jewish law, Moshe Ben Maimon, commonly known by the Greek version of his name, Maimonides (1138–1204 C.E.), referred to the Aleppo Codex when it was in Egypt and he was creating his magnum opus, the Mishneh Torah. As Maimonides reported, “Everyone relied on it, because Ben Asher had reviewed it.” Today all Torah scrolls in all Jewish communities everywhere in the world are written in accordance with the standard set by the Aleppo Codex, including precisely how the words are aligned. For example, they follow the detailed pattern in which the Song of the Sea (Exodus 15) is written.

For many years the Aleppo Codex remained the property of the Masorete who created it, Aharon Ben Asher. There is no original colophon in it, possibly because he had failed to find a patron to finance it. Its parchment is not the finest quality. The codex is distinguished by one thing: its superior scholarship. About a hundred years after it was created, a dedication was added to the end of the codex at the direction of one Israel Ben Simcha of Basra, a wealthy man who purchased the manuscript from the descendants of Aharon Ben Asher. It is only by means of this dedication that we can identify the scribe who wrote it and the great Masorete Aharon Ben Asher who was responsible for the notes.

Israel of Basra had the codex dedicated to the Karaite community of Jerusalem, where the codex was then taken. The Karaites, as opposed to the Rabbanites, were a dissident group of Jews who did not accept the Oral Law embodied in the Talmud. The Karaite elders, however, agreed to allow access to any scholar, whether Karaite or Rabbanite, seeking to ascertain the accurate Biblical text. Perhaps the heirs of Aharon Ben Asher made this a condition of the sale to the Karaites.

In 1099 the codex was seized by the Crusader conquerors of Jerusalem. They did not damage it, however, because they knew they could get a steep ransom price for it. We know of many Jewish manuscripts that were ransomed from the Crusaders; the Aleppo Codex was apparently one of them. Perhaps it was the Jews of Egypt who ransomed it, because the next we hear of the codex, it is in the synagogue of Fustat, near Cairo. The Fustat synagogue was a Rabbinic, not Karaite, synagogue; the codex has been in Rabbinic hands ever since. It was here that Maimonides used it in writing his Mishneh Torah. Because of Maimonides’ wide authority, the primacy of the Aleppo Codex was firmly established.

The next we hear of the codex—in the second half of the 15th century—it is in the Aleppo (Syria) synagogue. How it got there is not clear. We know that in 1375, a descendant of Maimonides, Rabbi David Ben Yehoshua, left Egypt and traveled through Palestine to Syria, taking with him many manuscripts and finally settling in Damascus and Aleppo. Perhaps the Aleppo Codex was among the manuscripts he took with him. In any event, it was there that it acquired its permanent name. In Hebrew, it is known as Keter Aram Tzova, “The Crown of Aleppo.” (Aram Tzova is a Biblical name—literally, the Tzova (district) of Aram (Syria)—that the Jews used for Aleppo.)

The codex remained undisturbed in the Aleppo synagogue for nearly 600 years, until December 1, 1947. The post-1947 history of the codex is hardly clearer than the earlier history. In the 1980s Amnon Shamosh, a prize-winning Israeli author and poet, was commissioned to write a full account of the Aleppo Codex and its history, including its travels and travails after the riots of 1947. I served as Shamosh’s research assistant for the book, which was published in 1987 (Ha-Keter—The Story of the Aleppo Codex [Jerusalem]); unfortunately it has not yet been translated into English. Shamosh and I found nine different accounts concerning the damage to the codex. The more intensely we examine them, the more contradictions arise.

Communication with Syria was extremely difficult in the years after 1947, especially for Israelis. Rumors circulated that the Aleppo Codex had been burned or destroyed. The great Hebrew University Bible scholar Moshe David Cassuto even eulogized the Aleppo Codex in an article in Haaretz:

If there is truth to the reports that have been published in the press, the famous Bible that was the glory of the Jewish community of Aleppo—the Bible which, according to tradition, was used by Maimonides himself—has been consumed by fire in the riots that broke out against the Jews of Aleppo some weeks ago; “the Aleppo Codex … is lost; it is no more.”

Fortunately, the rumors of total destruction turned out to be wrong.

During this period the main priority was rescuing Syrian Jews who wanted to leave. Israeli immigration authorities maintained an office in Istanbul, Turkey, and the personnel there were responsible for getting Jews out of Syria. The Turkish authorities often placed obstacles in the way of the Jewish Agency representatives, who resorted to operating secretly. They used code names in their letters, bribed clerks and airline and maritime personnel, and generally relied on resourcefulness and inventiveness.

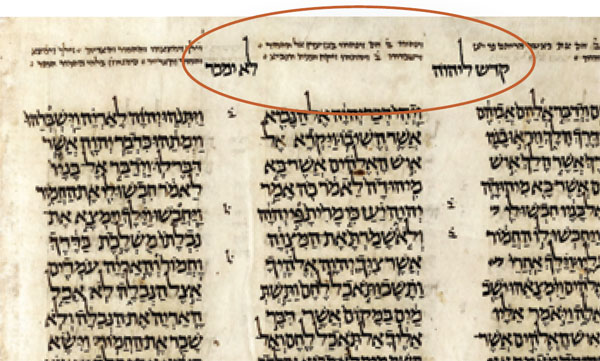

When rumors emerged that parts of the Aleppo Codex had survived the riots, considerable efforts were made to persuade members of the Aleppo community to smuggle it to Israel. The chief rabbi of Israel, Rabbi Ben-Zion Uzziel, wrote to the leaders of Jewish communities throughout the world to urge their support for the project. Aleppo’s rabbis, however, resisted. The dedication of the codex says it is “Holy unto the Lord. It shall not be sold or redeemed.” This warning was written again and again on the top of the codex’s pages. Aleppo’s Jews believed that on the day the codex was removed, their community would be destroyed. Rabbi Uzziel tried to allay these fears in one of his letters:

I have heard it said that the members of the Aleppo community are fearful of laying a hand on this holy book, owing to the curse that is written in it concerning anyone who moves the codex from its place. But now, since the codex has already been uprooted from its place and has been removed from the hands that had protected it, this fear is baseless.

In the fall of 1957, Yitzhak Pessel, a member of the Jewish Agency in Turkey, reported that “all attempts to persuade the heads of the [Aleppo] community to transfer it [the Aleppo Codex] to Israel have been met with opposition.” But, his report continued, he was successful in convincing Aleppo’s rabbis to change their position. Perhaps Rabbi Uzziel’s letter had some effect. In any event, sometime toward the end of 1957, the rabbis of Aleppo appointed a merchant named Mordechai Faham as their emissary and entrusted him with the mission of conveying the remains of the precious document to a safe haven. Pessel’s memo reported that Faham had successfully smuggled the codex out of Syria to Turkey and would bring it to Israel “after the holidays [Rosh Hashanah, Yom Kippur and Sukkoth].”

On December 11, 1957, Pessel sent a telegram from Istanbul: “30 people are setting sail today on the Marmara. Among the passengers is Mr. Faham.” The Aleppo Codex—the part of it that survived—was with him.

Upon the ship’s arrival in Israel, the codex was presented to the president of the state, Yitzhak Ben-Zvi.

But the codex was not complete! Faham brought with him only 294 pages of the original 490. Most important, all but the last 11 pages of the Pentateuch were missing. The final few pages of the Biblical text were also missing, as well as a few pages from the Prophets and other books.

Earlier in this article I quoted from the report of the caretaker’s son who entered the synagogue right after the riots. Shaul Baghdadi’s son reported that he found the Books of Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus and Numbers among the leaves that he picked up from the floor of the synagogue after the riots. Where are these leaves?

Another report from someone who entered the synagogue on the third day after the riots says he found the codex still on the ground with the Pentateuch missing up until the portion of “ki tavo” (Deuteronomy 26–29; actually the surviving pages begin at Deuteronomy 28:17).

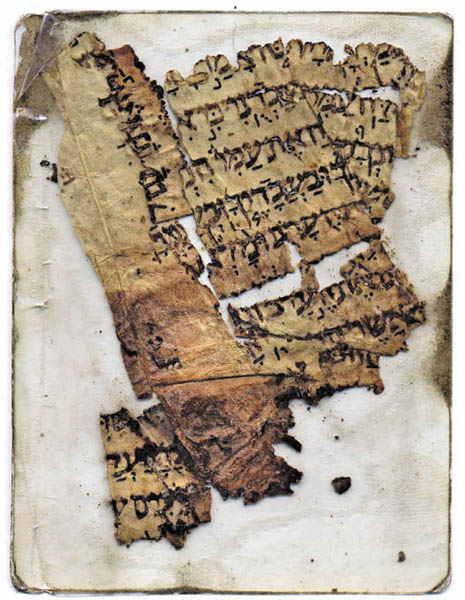

Perhaps whoever gathered up the remains of the codex after the riots did not bother with fragments of pages, only whole pages. A page from the Book of Jeremiah appears to have been deliberately shredded as if with a sharp knife. Six pieces have been recovered and were glued together. But about a third of this page is still missing.

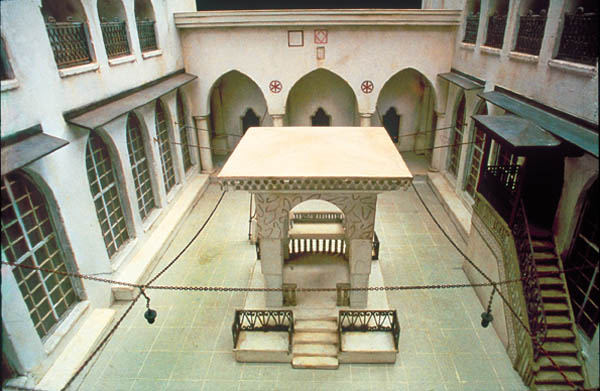

Another report comes second-hand from someone who was present “at the time of the fire.” According to this report (by Eliya Arkanji, not otherwise identified), “The pages that were torn from the codex could not be buried in the cemetery [as would be required of any holy document], for lack of time; instead they were placed in Beit El-Zeit, in the inner court, alongside the liwan.” Liwan in Arabic refers to the raised part of a hall, where the guests sit. Is there any chance that this liwan can still be identified?

And what happened to the codex between its post-riot rescue in 1947 and 1957, when it was smuggled out of Syria? Where was it secreted? Were some leaves or fragments stolen? Were some in the possession of rioters?

Were portions of the codex burnt in the riot? Except for one page, the extant pages that Faham brought to Israel are complete and show no evidence of fire damage. On the other hand, President Ben-Zvi’s notebooks, which I examined after he died, mention an Aleppo rabbi who said that some pages were burned. This rabbi, Yitzhak Shchebar, fled to Argentina; he has since died. But his report is borne out by the Exodus fragment, discussed below, that was recently recovered from Sam Sabbagh. According to the experts at the Israel Museum, it reflects clear signs of fire-related damage.

It is also possible that some of the rioters stole the missing pieces. In 1995 a certain Rabbi Yaakov Atiya told of this incident:

“One day, as I was leaving the yeshiva, an Arab policeman approached me, holding part of the codex. He asked me if it was part of the [Aleppo] Codex, and I saw that he was holding part of the page with the psalm, ‘Lord, who will dwell in Your tent,’ etc.”

The entire Book of Psalms was in the part of the codex that Mordecai Faham brought to Israel, except for two pages containing Psalms 15–24. Psalm 15 begins, “Lord, who will dwell in Your tent, who will sojourn on your holy mountain,” the part in the hands of the Arab policeman.

If these two pages were stolen by Syrians, there may be others.

Some fragments were also undoubtedly picked up from the synagogue by Jews. In 1947, when the riots occurred, Mary Hadaya, formerly of Aleppo, was living in Brooklyn. Concerned for her sister and her family still in Aleppo, Hadaya sent airplane tickets to bring them to New York. When they arrived, in a gesture of gratitude, Hadaya’s sister gave Hadaya a page from a holy book that she said would guard her and her household from all harm. In 1981 Hadaya’s husband passed away. When the family’s rabbi came to pay a condolence call, Hadaya showed him the piece of parchment that had lain in a wardrobe drawer for 34 years. He immediately recognized it as a page from the Aleppo Codex. She graciously returned it to Jerusalem, at the urging of the rabbi.

A similar scenario occurred with Sam Sabbagh, an Aleppo-born Jewish man who lived in New York. In 1988 information surfaced that he had a fragment of the Aleppo Codex. He carried it in his wallet in a clear plastic sheath. For him, it was a protective amulet; he agreed to send only a copy of it to Israel. In December 2007, however, after his death, his family relinquished this fragment of the Aleppo Codex and sent it to Israel. There were actually four fragments. The laboratories of the Israel Museum removed them from the sheath to which they were stuck and carefully straightened the four pieces which formed a single fragment that included a description of the plague of frogs on one side (Exodus 8:3–12), and the plague of wild beasts on the other (Exodus 8:16–26).

What other pages or parts of pages are still out there, whether in the hands of Jews or Syrians, we cannot know.

It is now 60 years since rioters savaged the “Crown of Aleppo.” But the search for the remaining pages continues.