Um el-Kanatir: Putting Humpty Dumpty Back Together Again

040

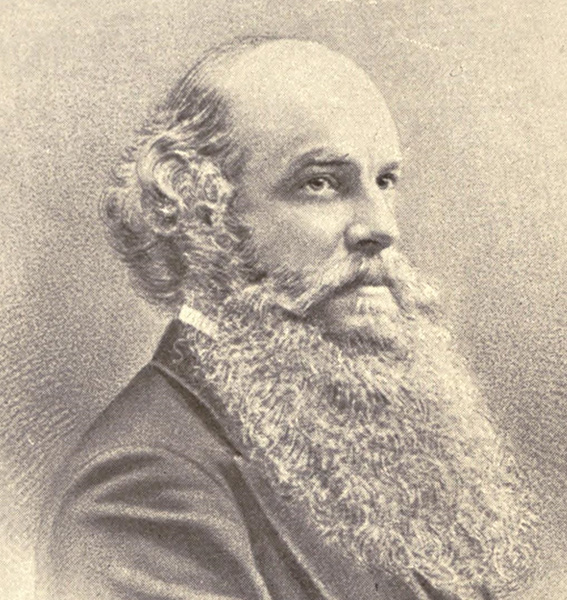

Accompanied by a local sheikh, Laurence Oliphant—a British diplomat, Member of Parliament, Christian mystic and Holy Land traveler—was exploring the slopes high above the eastern shore of the Sea of Galilee when he came upon the ancient stone arches over a generous cold-water spring. It was called Um el-Kanatir, the “mother of arches,” he was told. Nearby were the ruins of an ancient village, in the center of which was a great pile of ashlars (dressed stones)—obviously the remains of a once-large decorated public building.

Oliphant wrote:

Some two thousand feet below us, distant not more than seven miles, gleamed the still waters of the Sea of Galilee. We stood on the upper edges of one of the branches of the Wady Samak, which leads down to it … one of the most delightful scenic surprises which it was possible to imagine. Here in the wild, inaccessible spot, in ages long gone by … a copious fountain of water … with blocks of stone of immense size …

[The walls of the public building were] still standing to a height of about seven feet. … These walls enclosed an area of about fifty feet by thirty-five feet, which was covered by a mass of ruins which had been tossed about in the wildest confusion. … Six columns, varying from ten to twelve feet in height, rose from tumbled masses of building-stone at every angle. …

I had discovered the ruins of an ancient Jewish synagogue. … Altogether I regard these ruins as the most interesting discovery045 I have yet made, and as being well worthy of another visit and a more minute examination.1

The year was 1884. Oliphant was the first westerner to visit the synagogue of Um el-Kanatir.

The building was partially excavated for four days in 1905 by Heinrich Kohl and Carl Watzinger, the well-known scholars of Galilean synagogues. For the next hundred years, this would serve as the basis for its study.

Since that time, several other scholars and surveyors have visited the site and reported on it briefly, including Eliezer Lipa Sukenik, Yigael Yadin’s father.

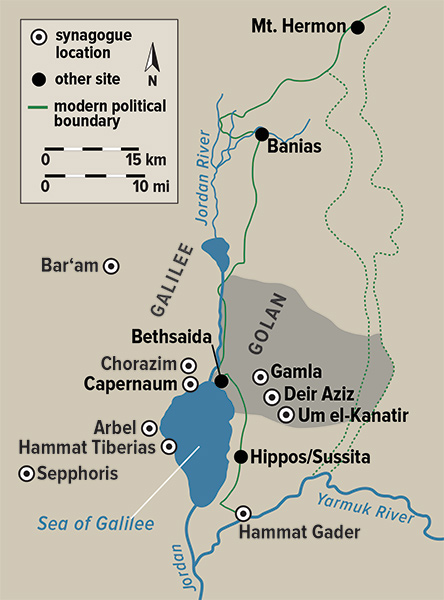

Some 26 ancient Byzantine synagogues have been identified on the Golan Heights. Um el-Kanatir is unique, however, in that most of the stones seem to be in situ where they fell in an enormous pile of ashlars strewn on the ground.

One day in 2001, I received a visit from my friend Yeshu (his full name is Yehoshua [Joshua] Dray, but everybody calls him Yeshu) when I was excavating an ancient synagogue at nearby Deir Aziz.a

After visiting Deir Aziz, he and I went to Um el-Kanatir. Yeshu’s specialty is the reconstruction and restoration of ancient sites and devices. He has been in the field for a quarter of a century. Most of his reconstructions and restorations are experimental, but are fully operational—although not fully accepted in the academic world. His restorations include olive oil factories, flour mills operated by water power (or by beasts), water-lifting devices for ancient wells, wineries, locks for doors and means for coin minting. Most archaeologists try to identify and date what they find; Yeshu asks, “How does it work? How was it created?” For years, Yeshu has advised archaeologists on how to solve complicated archaeological puzzles.

When we visited Um el-Kanatir, Yeshu went wild: “You have here the remains of an almost whole building. Here you can really understand how a synagogue building looked.”

042

I’m sure that many scholars have thought about this, but no one had any idea how to lift these hundreds of stones and put them together as they once were. When I suggested the difficulty of this to Yeshu, a devilish smile ran across his face. “No problem,” he said. We decided to collaborate on the project. But this time, instead of being a restoration adviser, Yeshu would be the project director.

Work began in the summer of 2003. It has taken 12 years to reconstruct 50 percent of the original building. Each stone has been placed specifically to fit each of those flanking it. Under the direction of main field archaeologist Ilana Gonen Chaim, we worked the equivalent of043 approximately 600 days, spending half the time excavating and half reconstructing.

In order to move the heavy blocks of stone piled in heaps on the floor, we installed an overhead crane, also called a bridge crane, commonly found in industrial settings. It consists of steel runways on either side of the site with an overhead bridge running between the two tracks supported by vertical steel legs that can move on the steel side tracks. A steel lift hangs from the bridge. When the bridge is appropriately placed, the overhead bridge can be moved along the tracks. In this way the lift can be located anywhere over the site. And it can be lowered to lift any particular block of stone.

But that’s only the beginning. Identifying each block of stone and determining how it fits with other stones is more difficult.

We first mapped the site with a high-resolution three-dimensional (3D) laser scanner, a computerized remote sensing technique that automatically measures the entire object at any desired scanning resolution. This technology has dramatically changed the quality of geometrical documentation, providing accurate, detailed, 3D measurements.

This 3D laser scanning provides elevations, as well as the precise location and position of every stone in the heap on the ground. The resulting measurements are 3D and fully compatible with architectural software such as AutoCAD, a commercial software application for 2D and 3D computer-aided design (CAD) and drafting. Three-dimensional mapping replaces conventional methods of measurement; the print-outs of the computer imaging become the working plans in the field. Precise laser mapping identifies deviations in the structure and provides an infinite number of sections and cross-sections of every component of the building.

The data regarding the various architectural elements are then fed into the excavation database, giving each architectural element an “identity card,” including measurements, type, direction of collapse, its 3D location in the heap and whether the original location of the displaced element could be distinguished in the structure. Each architectural element (such as a block of stone) was identified by inserting into it a 3- by 10-mm RFID microchip.044 Radio-frequency identification (RFID) is the wireless use of electromagnetic fields to transfer data for the purpose of automatically identifying and tracking tags attached to objects. The tags contain electronically stored information and can be attached to clothing and objects or implanted in animals and people. A chip reader is then passed over an object to extract its “identity card.” The use of electronic chips ensures that the marking will last, with negligible damage to the object.

We excavated heaps of stones piled on the floor. The pieces included column shafts, bases and capitals. There were also some engaged columns. Parts of the walls included headers and stretchers. Other blocks formed doorposts, lintels and thresholds.

Our initial assumption that the collapse was the result of an earthquake and had lain undisturbed thereafter had to be modified slightly. This was shown045 by the discovery of secondary construction, consisting of the remains of the walls of four rooms in the northern part of the building. These rooms were built after the collapse, and their walls incorporated architectural elements from the ruined synagogue. The finds from these four rooms can be dated to the first half of the eighth century C.E., which tallies with the destructive earthquake of 749 C.E. After that earthquake, the building was abandoned and never reused.2

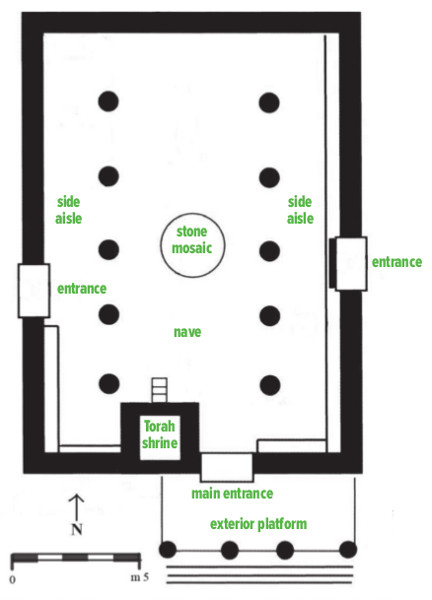

The earlier, now-restored synagogue, which dates to the second half of the sixth century C.E., is a046 basilical structure measuring about 45 by 62 feet. It features two rows of columns (five on each side) that divide the hall into a nave and two side aisles. This structure once rose to a height of two stories and supported a gabled roof of clay tiles.

The well-preserved synagogue floor was paved with basalt flagstones featuring a unique element: In the center of the nave, the flagstones were set in an octagonal pattern enclosed within a circle.

We also found almost 7,500 coins, apparently the result of a custom of dispersing coins as floor foundation deposits to ensure good luck—a phenomenon known from other Byzantine-period synagogues.

Below this synagogue was another structure dating to the third century C.E. with a row of benches lining three of its walls. The eastern row of benches also had a footrest. We are not sure whether this047 structure was also a synagogue.

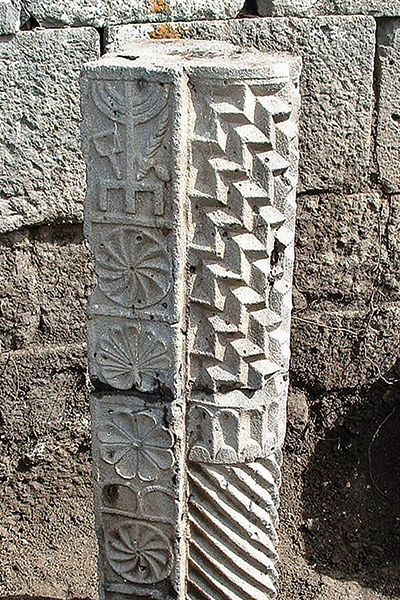

The highlight of the excavation, however, was not the discovery of this earlier building, nor the construction of the four rooms later built on the northern side of the structure, but the aedicula (or raised platform) for the Torah shrine on the southern wall of the synagogue between the two rows of columns. A stone structure that rose nearly 20 feet, the aedicula was ascended by a narrow, stylized staircase. On the platform of the aedicula were two richly decorated columns with reliefs of vines emerging from amphorae. At the top of each column was the relief of a seven-branched menorah.048 One of the menorahs is accompanied by a common set of symbols found in mosaic floors of many Byzantine synagogues—an incense shovel, a shofar (ram’s horn) and an etrog (lemon-like fruit) and lulav (palm frond) used on the festival of Sukkot.

Also on the southern wall was a broad doorway that was apparently set as far to the east as possible to allow more space for the Torah shrine.

Torah shrines like this are often portrayed in mosaic floors of Byzantine synagogues, but this is the first time that almost all these elements are found in an excavation. In short, the synagogue mosaic floors of Torah shrines were realistic. Apparently these Torah shrines were meant to resemble the entrance to the Temple in Jerusalem.

Anastylosis is a Greek term referring to restoration of an ancient structure using only original architectural elements. That is what we have done049 with the ancient synagogue at Um el-Kanatir. At this time, all four ground-floor walls of the synagogue have been reconstructed to their full height (about 15 ft), along with the two rows of columns and the aedicula for the Torah shrine.

The western wall of the synagogue featured windows and a doorway. The northern part of the wall has two rectangular windows (measuring 1.8 x 2.62 ft). On the other side of a doorway in the wall is a round window (2.6 ft in diameter). The keystone of this window features the relief of a lion with a protruding tongue and front paws outstretched.

Two rows of columns, five in each row, stand to a height of more than 12 feet on the floor of the synagogue. Their pseudo-Doric bases and capitals bear an impressive architrave.

The excavation and reconstruction of the Um el-Kanatir synagogue is of groundbreaking significance because of its advanced methodology and the scientific reconstruction of the entire building. Care has been taken so as not to lose even the smallest piece of information about the building’s character, its construction technique and how it eventually collapsed.

These scientific methodologies bring the fields of conservation and restoration into the 21st century.

Excavations at Um el-Kanatir are unique in that they are not destructive, but rather reconstructive. The almost complete remains of the ancient synagogue nestled into its picturesque setting are proving to be a high-tech puzzler’s dream.

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Footnotes

1.

Chaim Ben-David, “Golan Gem—The Ancient Synagogue of Deir Aziz,” BAR 33:06.

Endnotes

1.

Laurence Oliphant, Haifa, or Life in Modern Palestine (Edinburgh and London: W. Blackwood and Sons, 1887), pp. 262–265.

2.

We speculate that the initial collapse was caused by an unusually heavy snowstorm that collapsed the heavy roof tiles—and then the walls fell apart.