What’s in a Name? Personal Names in Ancient Israel and Judah

046

Personal names change over time. Based on Social Security card applications, the five most popular given names for female babies born between 2010 and 2018 were Emma, Sophia, Olivia, Isabella, and Ava. During the 1910s, 100 years earlier, those names were Mary, Helen, Dorothy, Margaret, and Ruth. Today an increasing number of parents are choosing unisex names for their children. Similarly, names in the Bible differ from one period to another. Many personal names mentioned in the context of the First Temple period include a Yahwistic element—that is, yhw/yh/yw (Hebrew: יו/יה/יהו). Examples include Hezekiah (Hizqiyahu; חזקיהו), Yoram (יורם), and ‘Uzziyah (עזיה). However, few such names are evidenced in the context of the Exodus and the conquest of Canaan.

Can changing naming characteristics contribute to the study of historicity in the Bible?

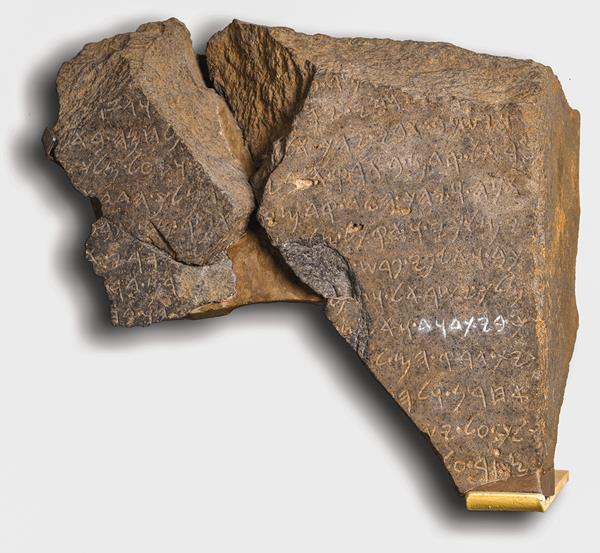

Previous onomastic studies focused on the names themselves rather than trends in their characteristics in order to establish biblical historicity. They search the archaeological record for names of biblical figures. The most famous example is the Tel Dan inscription that mentions a king of “the House of David”—a reference to David as the founder of a dynasty. Until the inscription’s discovery in 1993, scholars debated whether King David was a literary or historical figure.

To date, the names of 53 biblical figures have been confirmed in authentic ancient Near Eastern inscriptions from the tenth to fifth centuries B.C.E. Out of these, eight are kings from the northern kingdom of Israel, and 14 are kings, members of the royal family, high officials, or priests from the southern kingdom of Judah.a Yet, these names are a fraction of the growing corpus of Hebrew names appearing in epigraphic (i.e., inscribed) artifacts found in Israel and Judah during the Iron Age II, also known as the First Temple period (from the tenth century to the Babylonian destruction of Jerusalem in 047586 B.C.E.). Much information is contained in this large corpus of names—in addition to the attestation of biblical figures.

This rich onomastic data offers another approach of examining biblical historicity. More specifically, comparing characteristics of names from authentic Iron Age II epigraphic artifacts and those mentioned in biblical narratives of the same period—the First Temple Period—can shed more light on the extent of historicity in the Bible. Differences in the characteristics of the two groups might indicate that biblical names in the context of the First Temple Period are not genuine, that is, they originated in later periods or were invented. By contrast, similar characteristics of names from biblical and epigraphic sources would indicate that the biblical narratives of the two kingdoms reflect authentic onomastic traditions. When comparing archaeological evidence and the Bible, biblical names have an advantage over biblical stories because names generally tend to be less influenced by the editor’s ideological and theological concepts.

Before delving into the characteristics of Iron Age II Hebrew names, let me say a few words about these names. Many personal names of this period reflect religious beliefs and the deities that were worshiped. Consequently, the names are divided into three categories. The first and largest category, theophoric names, is composed of sentence names compounded with a divine name or divine appellative. Examples of divine names are Yahweh (יו/יה/יהו), Horus (חור), and Môt (מות). Examples of divine appellatives are “lord” (אדן), “king” (מלך), and familial nouns such as “father” (אב), “brother” (אח), and “uncle/kinsman” (עם) in 048which the deity was perceived as part of the family. El and Baal are both ambiguous. Baal is the Canaanite storm god but is also the divine appellative “lord/master” and may refer to any god. El is the head of the Canaanite pantheon and is also a general term for god. Examples of theophoric sentence names are Gedaliah (2 Kings 25:22), which means “Yahweh was great,” and Nethaniah (1 Chronicles 25:12), meaning “Yahweh has given.”

The second category of names is composed of hypocoristic (abbreviated) theophoric names where the theophoric element fell away, such as Shema‘ (שמע; 1 Chronicles 11:44), an abbreviation of Shema‘yahu (שמעיהו) or Elishama‘ (אלשמע). Divine appellatives may refer to a particular deity, but it is impossible to tell which deity.

The third category comprises names with no religious meaning. Examples include fauna: “grasshopper” (Hagab; חגב; Ezra 2:46), “dog” (Caleb; כלב; Joshua 14:6), and “fox” (Shual; שוּעל; 1 Chronicles 7:36); flora: “pomegranate” (Rimmon; רמון; 2 Samuel 4:2) and “palm tree” (Tamar; תמר; 2 Samuel 13:1); appellatives: “bald” (Kareah; קרח; 2 Kings 25:23) and “boor/witless” (Nabal; נבל; 1 Samuel 25:3); or substitute names, that is, names that designate the name-bearer as a substitute for a deceased relative: “paternal uncle” (Ahab; אחאב; 1 Kings 16:29) and “he who comforts” (Menahem; מנחם; 2 Kings 15:14).

Now that I’ve established some types of personal names, how to analyze them?

Researchers studying modern naming characteristics have the data at their fingertips. The Social Security Administration keeps millions 049of naming records for more than a hundred years. These records are available online; see www.ssa.gov/oact/babynames for popular baby names by year, decade, state, or U.S. territory.

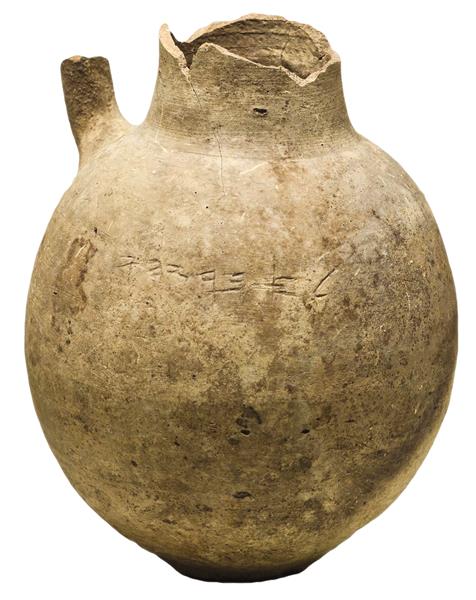

Researchers of ancient names need a similar collection of naming records to do the same type of onomastic study. Hence, I built a comprehensive database of Iron Age II names and their various characteristics. The personal names were collected from excavated Iron Age II epigraphic artifacts, such as incised inscriptions, ostraca (inscribed potsherds), seals, bullae (small pieces of clay with a seal impression on them, sealing documents or packages), and stamped or inscribed jars. Names found in artifacts from the antiquities market were excluded since their context, such as their geographical origin and date, is unknown, and their authenticity is uncertain. Each name is analyzed according to different categories: name, artifact type (the artifact in which the name appears), artifact site (where the artifact was found), territorial affiliation (e.g., Israel or Judah), prefixed/suffixed theophoric element (included in the name), and bibliography.

Recently, the entire database was made available online at www.onomasticon.net.1 The site is intended for scholars and laypeople alike. You can pursue research ideas by performing complex searches against the database or simply look for specific names. The digital onomasticon has many advantages over a printed one—the primary one being the ability to update data frequently. Names are added as new epigraphic artifacts are discovered. Existing names are updated as old artifacts are re-examined using new technologies. New categories can be inserted for studying additional aspects of personal names. Another advantage is immediate answers. Users can even download their search results to a PDF file.

Currently, the digital onomasticon comprises about 950 names mentioned in approximately 470 artifacts from 80 sites. This large onomasticon enables us to apply quantitative analysis and reach statistically meaningful conclusions. It is important to note that unlike the Social Security Administration’s database of U.S. names, it does not contain all names used in the southern Levant during the Iron Age II but only those found in archaeological excavations.

Since archaeology is not a perfect record of history, the onomasticon does not represent all social strata equally. It includes only names collected from epigraphic artifacts, which have a connection to literacy and administration, two characteristics that tend to be associated with higher social strata. This is also true for names found in the biblical narratives, which mainly include those of kings, high officials, priests, officers, and their genealogies.

So what does the onomasticon reveal? Are the characteristics of Iron Age II names in the biblical narratives similar or different from those collected from excavated epigraphic artifacts?

Consider the Book of Jeremiah. The majority of the persons mentioned in the book are Judeans, contemporaries of the prophet Jeremiah, as are their ancestors, typically fathers and sometimes 050also grandfathers. Thus, the digital onomasticon was searched for names affiliated with Judah in the seventh and early sixth centuries (Jeremiah’s time). These names were compared with Judean names appearing in Jeremiah in the context of the same period.

The names, 92 from Jeremiah and 367 from epigraphic artifacts, were sorted into six groups according to their theophoric elements. Yahwistic names were the most dominant group (63 percent in Jeremiah and 50 percent in epigraphic artifacts), followed by a large margin by names with El (10 percent in Jeremiah and 8 percent in epigraphic artifacts). Names with divine appellatives and divine names other than Yahweh and El in both sources are rare.

In addition, each source was analyzed according to the location of Yahwistic elements yhw (יהו) and yh (יה) within the names: whether they were prefixed or suffixed. There was very similar distribution of the prefixed and suffixed element yhw (יהו)—87 percent and 13 percent, respectively, in Jeremiah and 93 percent and 7 percent in epigraphic artifacts. Yh (יה) is always suffixed in both sources. The number of names with other theophoric elements—el (אל), yw (יו), divine appellatives, and other divine names—is too small for comparing prefixes and suffixes.

Several popular names are common to both sources: Shema‘yahu (שמעיהו), Ḥananyahu/Ḥananya (חנניהו/חנניה), Shelemyahu/Shelemyah (שלמיהו/שלמיה), and Shallum (שלם). Moreover, šlm (שלם; meaning “be safe, unharmed”; “be in peace”; “pay, replace”) is a popular element in names: Shelemyahu/Shelemyah (שלמיהו/שלמיה) and Shallum (שלם) in Jeremiah, and Tobshalem/Tobshillem (טבשלם), Shelemyahu/Shelemyah (שלמיהו/שלמיה), and Shallum (שלם) in epigraphic artifacts.

Another comparison examines the distribution of the Yahwistic elements (יו/יה/יהו) in each source. Although names with yhw (יהו) are the 051largest group in both sources, the distribution is clearly different: While in the epigraphic record yhw (יהו) is the dominant element (98 percent), and yh (יה) is rare (2 percent), in Jeremiah both yhw and yh are common (53 percent and 42 percent, respectively). Yw (יו) is rare in both sources. The frequent use of yh in Jeremiah versus its rare appearance in the epigraphic record possibly reflects either the view of some authors and redactors of Jeremiah that yhw and yh are interchangeable, or the inclination to update Judean names by substituting yhw by yh. Yh is the dominant Yahwistic form in names from the Second Temple period.

In summary, the similarities in characteristics of personal names in Jeremiah and excavated epigraphic artifacts help support the scholarly arguments for the historicity of Jeremiah, at least as far as names are concerned. Nevertheless, the differences found in the distribution of yhw and yh between the two sources suggest that the names in Jeremiah underwent a process of redaction.2

I also analyzed the characteristics of personal names appearing in the books of Kings and Chronicles in the narratives of the Divided Monarchy and the Kingdom of Judah after the destruction of Israel.3 I compared these names with those of epigraphic artifacts found in Israel and Judah in the same period (ninth to the early sixth centuries B.C.E.). The very limited number of epigraphic artifacts and names from the tenth century does not enable us to perform similar comparison with the many names mentioned in the United Monarchy narratives. In all, the comparison involves 339 theophoric names from archaeological sources and 215 names from biblical sources: 68 from the books of Kings, and 147 from the books of Chronicles.

For brevity, I will present only the main results of this comparison: Theophoric Judean names from biblical and epigraphic sources are similar, while theophoric Israelite names from biblical sources are entirely different from those from epigraphic sources. The distinct characteristics of the theophoric Israelite names in epigraphic artifacts—the dominant use of Yw, the absence of yhw and yh, and the use of the divine name Baal—are not found in the Bible. Theophoric Israelite names in the Bible are similar to Judean names. These results indicate that the Bible reflects authentic Judean but not Israelite onomastic traditions.

This demonstrates how www.onomasticon.net sheds light on one aspect of the relationship between the Bible and archaeology. The onomasticon’s potential to contribute to future onomastic, archaeological, and biblical research is immense, especially with regard to future discoveries of Hebrew inscriptions.

Explore how ancient Israelite and Judahite personal names—collected from archaeological materials—contribute to the study of the Bible’s historicity.

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Footnotes

1. See Lawrence Mykytiuk, “Archaeology Confirms 50 Real People in the Bible,” BAR, March/April 2014 and “Archaeology Confirms 3 More Bible People,” BAR, May/June 2017.

Endnotes

1.

The Research Software Company (www.researchsoftware.co.il), which provides software development resources for academic researchers, developed www.onomasticon.net. Special thanks go to Itay Zandbank, CEO.