028

To understand the valleys of Jerusalem, it helps to know the different kinds of valleys encountered in the ancient Land of Israel (Eretz Yisrael). There are at least five Hebrew words designating the variety of valleys in biblical times.

A large valley with water flowing intermittently is a nahal, corresponding to wadi in Arabic. Except during the rainy season, a nahal is dry.

A broad, low-lying plain is an ‘emeq, meaning “depression.” An ‘emeq is not as broad as a biq‘ah, a wider, low-lying plain.

A narrow gorge is a gai’. The word can be translated simply as “Valley.”

A valley in the sense of a lowland is shephelah, from the verb meaning “to be or become low.” The Shephelah is the designation for the foothills lying between the Mediterranean coastal plain and the central mountain range of Israel.

These distinctions obviously can be important for understanding a biblical text. Like other geographical terms, they have at least two aspects—one comes under the rubric of physical geography; the other, under the rubric of historical geography. Physical geography is concerned with the configuration of the terrain; historical geography deals with the use of the land and its effect on the life of the people.

Valleys often serve as natural borders and natural defenses. One of the valleys of Jerusalem, as we shall see, marked the border between Judah and Benjamin. Valleys also had important implications for the conduct of warfare. In the valleys, grain was grown, herds were grazed and vineyards and orchards were cultivated.

In addition, valleys in the Bible sometimes have metaphorical meanings. In Psalm 23 (“The Lord is my shepherd”), verse 4 may be translated: “Even though I walk through the darkest valley…” (or, more familiarly, “the valley of the shadow of death”). The valley is a place of danger and loneliness.

Consider another example: When Isaiah foretells that the Lord will remove all obstacles from the path of the exiles 030returning from Babylonian captivity, the prophet says: “Every valley shall be lifted up, and every mountain and hill be made low” (Isaiah 40:4).

Jerusalem, “the holy city” (Isaiah 52:1), is defined by valleys. Situated on a limestone plateau about 2,500 feet above sea level, Jerusalem is built upon two hills—the eastern hill and the western hill. Deep valleys surround Jerusalem on three sides, making this hilltop city quite defensible. The northern side, however, lacks a natural defense. This side has always been vulnerable, and has usually been the first point of attack in war. (A popular interpretation of the name “Jerusalem” is “the city of peace”; ironically, Jerusalem has been a battlefield for centuries.) Both the Babylonians (in 586 B.C.E.a) and the Romans (in 70 C.E.) succeeded in destroying Jerusalem by first breaching the northern wall of the city.

The three principal valleys of Jerusalem are the Kidron on the east, the Hinnom on the south-west and south and the Central (Tyropoeon) Valley, dividing the city in half. These three valleys converge in the vicinity of the Gihon Spring, southeast of Jerusalem. In antiquity these valleys were deeper and more precipitous than they are today. Over the centuries, they have partially filled up with accumulated debris. This is especially true of the Central Valley.

The Kidron valley, running on a north-south axis, separates Jerusalem from the Mount of Olives on the east and northeast. South of Jerusalem the Kidron takes a turn eastward and extends as far as the Dead Sea. In antiquity, the Kidron marked the eastern boundary, of Jerusalem. Ordinarily dry, the Kidron is designated a nahal.

The Nahal Kidron figures in two critical events recorded in the Bible. David in his flight from Jerusalem during the rebellion of his son Absalom, passed over the Kidron (2 Samuel 15:23). Jesus and his disciples, on their way to spend the night at Gethsemane after leaving the Upper Room, also crossed the Kidron (John 18:1).

In the Nahal Kidron (sometimes translated “brook of Kidron”), King Asa of Judah (913–873 B.C.E.) destroyed the idols of his Geshurite mother (1 Kings 15:13; 2 Chronicles 15:16). Likewise, the two great kings of Judah who mounted religious reforms, Hezekiah (715–687 B.C.E.) and Josiah (640–609 B.C.E.), destroyed heathen idols and illicit cult objects in the Nahal Kidron (2 Kings 23:4–12; 2 Chronicles 29:16, 30:14). The Kidron may have been chosen because it was outside the boundaries of Jerusalem.

The upper Kidron, the part between the Mount of Olives and the Temple Mount, is also known as the Valley of Jehoshaphat. Jehoshaphat was a king of 031Judah in the ninth century B.C.E., but this part of the Kidron is named the Valley of Jehoshaphat not because of any association with the king of that name, but because of the meaning of the name. Jehoshaphat “Yahweh shall judge.” The Valley of Jehoshaphat is a play on the name. The biblical source for this popular designation is the prophet Joel, who lived in the post-Exilic period (that is, after 538 B.C.E., the date when the Jews began to return from the Babylonian Exile). According to Joel, God will assemble all the nations of the earth in the symbolic Valley of Jehoshaphat (the valley of “Yahweh shall judge”) and there judge, rendering a decision against Israel’s enemies: “I will gather all the nations and bring them down to the Valley of Jehoshaphat, and I will enter into judgment with them there, on account of my people and my heritage Israel, because they have scattered them among the nations” (Joel 3:2 [4:2 in Hebrew]). The same thought is repeated in Joel 3:12 (4:12 in Hebrew).

In Joel 3:14 (4:14 in Hebrew) the symbolic name “the Valley of Decision” is substituted for “the Valley of Jehoshaphat.”

These texts gave rise to the belief that God’s final judgment would be rendered in the Valley of Jehoshaphat on the east side of Jerusalem. This area, understandably, became the favorite burial place in Jerusalem. Elaborate funerary monuments from the late second and first centuries B.C.E. are found in the Valley of Jehoshaphat. Among them are tombs with the popular names Zechariah, Jehoshaphat and Absalom. (These biblical luminaries, of course, lived much earlier than these Hellenistic funerary monuments that bear their names.) The so-called Tomb of Absalom, with its 60-foot-high conical top, is a well-known Jerusalem landmark.

In popular understanding, the site of the last judgment—that is, the Valley of Jehoshaphat—changed over the centuries: The location of the “Valley of Jehoshaphat” moved from the Kidron Valley to the Hinnom Valley, which in later tradition became known as the Valley of Jehoshaphat. Since the fourth century C.E., the name has been associated again with the Kidron Valley.

The earliest settlements in Jerusalem, including the City of David, were situated on the eastern hill, bounded by the Kidron Valley on the east and the Tyropoeon, or Central, Valley on the west. The site of these settlements on the eastern hill was determined principally by access to the Gihon Spring, a perennial freshwater source located on the west side of the Kidron Valley. Gihon, derived from the Hebrew word giha (gushing forth), is so called because its water gushes intermittently. Solomon was anointed king over Israel by the priest Zadok and the prophet Nathan at the Gihon Spring (1 Kings 1:33–45).

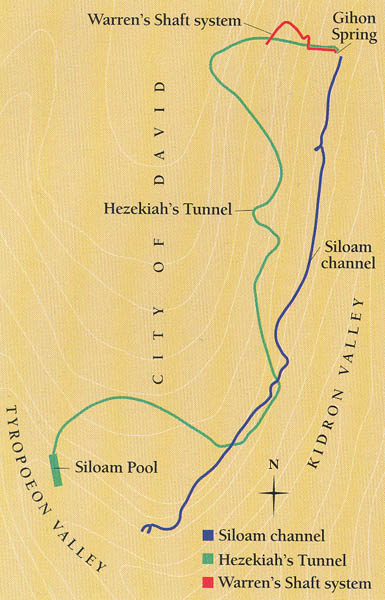

Over time, various conduits were dug to bring the water of the Gihon, which lies near the valley floor outside the city wall, into Jerusalem. In the period known as Iron Age II (1000–586 B.C.E.), the Gihon Spring fed three interconnected water systems. Warren’s Shaft (named after its modern discoverer Charles Warren of the London-based Palestine Exploration Fund) is the earliest of these systems. It consists of a 50-foot vertical shaft connected by tunnels to the surface of the hill above. During enemy attacks, this system provided Jerusalemites with access to water without their having to venture outside the city wall to reach the Gihon Spring.

The Siloam channel was the second of the water systems that began at the Gihon Spring. It functioned as a kind of aqueduct that carried water along the Kidron Valley to a reservoir at the southern tip 032of the city. Through apertures in the channel wall, it provided irrigation for the adjacent fields.

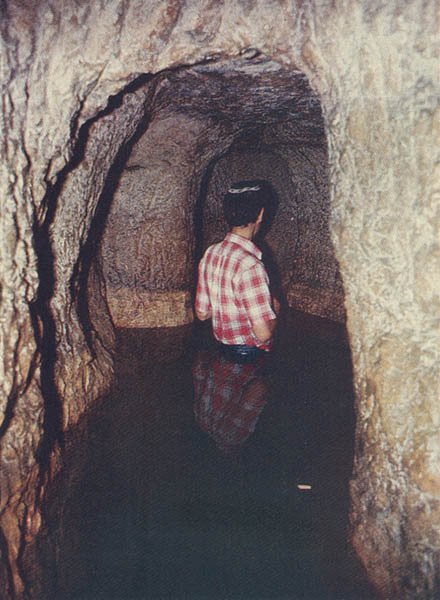

The best known of the three water systems that began at the Gihon Spring is Hezekiah’s Tunnel, an enclosed aqueduct or tunnel that diverted water from the Gihon Spring to the Siloam Pool at the southwest corner of the city. Measuring 1,750 feet, Hezekiah’s Tunnel was dug through solid bedrock to protect the water supply from Assyrian invaders led by Sennacherib in 701 B.C.E. The famous Siloam inscription, carved on the eastern wall of Hezekiah’s Tunnel near the southern end, describes in detail the excavation of the tunnel. Although Hezekiah’s name is not included in this monumental Hebrew inscription, he undoubtedly built the tunnel, which is even mentioned in the Bible (2 Kings 20:20; 2 Chronicles 32:30).

Opposite the City of David—the southeastern hill of ancient Jerusalem—is the present-day Arab village of Silwan. Silwan occupies a steep slope on the eastern side of the Kidron Valley. In the cliffs of this village, about 50 monumental tombs came to light during a survey conducted by Israeli archaeologist David Ussishkin, assisted by Gabriel Barkay. This eastern slope of the Kidron Valley once served as a vast cemetery. Dating from the ninth to the seventh centuries B.C.E., this necropolis, according to 033Ussishkin, may be the burial place “where nobles and notables of the kingdom of Judah were interred.”1 Ussishkin traces the origin of this tomb architecture—its gable ceilings, or straight ceilings with a cornice, an entrances situated high in a cliff or steep slope—to Phoenicia, on the northern Mediterranean coast.

Lying to the south and southwest of Jerusalem is the Valley of Hinnom, a tributary to the Kidron Valley. Also called the Valley of Ben (the son of) Hinnom and the Valley of Benei (the sons of) Hinnom, the Hinnom in ancient times marked the, boundary between the territories of the tribes of Benjamin and Judah. The Hinnom Valley acquired a sinister reputation because here, close to the junction with the Kidron, was the site of the cultic shrine called Tophet.

The word “Tophet” derives from the Aramaic tepat, denoting “hearth” or “fire place.” The vowels in the Hebrew form “Tophet” have been supplied from the Hebrew noun “boshet,” meaning “shame” or “shameful thing,” on account of the heinous nature of the place. The Tophet was a pagan open-air sanctuary or high place where human sacrifices were offered.

Biblical texts, especially Jeremiah, help to clarify the nature and function of the Tophet, but much remains to be learned. According to 2 Kings 16:3 and 21:6, Kings Ahaz (735–715 B.C.E.) and Manasseh (687–642 B.C.E.) consigned their sons to the fire at the Tophet. King Josiah (640–609 B.C.E.) dismantled the Tophet, as recorded in 2 Kings 23:10: “He [Josiah] defiled Topheth, which is in the valley of Ben-hinnom, so that no one would make a son or a daughter pass through fire as an offering to Molech.”

Speaking of the Tophet, Jeremiah delivers God’s message to the people of Judah:

“And they go on building the high place of Topheth, which is in the valley of the son of Hinnom, to burn their sons and their daughters which in the fire—which I did not command, nor did it come into my mind. Therefore, the days are surely coming, says the Lord, when it will no longer be called Topheth, or the valley of the son of Hinnom [ge’ ben-hinnom], but the valley of Slaughter [ge’ haharegah]: for they will bury Topheth until there is no more room” Jeremiah 7:31–32).

Jeremiah (32:35) as well as 2 Kings 23:10 refer, according to common English translations, to Molech, a deity of uncertain origin. Instead of “to Molech,” the translations should read “a mulk sacrifice,” a technical term denoting a live sacrifice in fulfillment of a vow.2 Some scholars argue that terms such as “passing over” (sons and daughters) and “burning in fire” connote an initiation rite, or are intended figuratively or are prophetic hyperbole. They maintain that children buried in the Tophet had died of natural causes, not as victims of sacrifice. Other scholars insist that the Hebrew phrase 052le he ‘avir ba’esh signifies literally “to pass through the fire and so burn.” They emphasize that biblical texts mean what they say, and when conjoined with extra-biblical texts and archaeological evidence—particularly that from the great Phoenician site of Carthageb—they cannot be interpreted figuratively.3

But the grim association with human sacrifice is not all that we are left with to- day in the Hinnom Valley. Excavations on the western slope of the Hinnom, designated now as the Shoulder of Hinnom (Hetef Hinnom), uncovered an extraordinary ancient biblical text. Between 1975 and 1980, Gabriel Barkay investigated nine rock-cut burial caves—perhaps family tombs—dating from the end of the First Temple period (late seventh to the early sixth century B.C.E.).4 In a large cache of gold and silver jewelry, Barkay discovered two seventh-century B.C.E. amulets, once worn as charms. These two small cylindrical silver objects, rolled into small scrolls, contain the text of a Hebrew prayer that includes the divine name, its occurrence on an object excavated in Jerusalem. The fragmentary text has been identified as the priestly benediction also found in the Book of Numbers: “The Lord bless you and keep you; the Lord make his face to shine upon you, and be gracious to you; the Lord lift up his countenance up on you, and give u peace (shalom)” Numbers 6:24–26)

Another name for the Valley of Hinnom is Gehenna, the Latin and English form of the Hebrew ge’-hinnom (Valley of Hinnom). In the time of Jesus, the name Gehenna was associated with the Valley of Hinnom. By the fifth century C.E., however, confusion about the tradition led to transference of the reputed site of Gehenna to the Kidron Valley, on the eastern side of Jerusalem.

In the New Testament and in rabbinic literature, Gehenna designates the place where the deceased are to be judged and punished after death. The New Testament makes a distinction between Hades (the abode of the dead), which is temporary, and Gehenna, which is permanent. But the Gehenna of rabbinic literature does not have the connotation of eternal punishment. Never used as a geographical place-name in the New Testament, Gehenna is rich in symbolic meaning. It is used metaphorically to designate a place of unquenchable fire (Matthew 5:22; Mark 9:43–48), a fiery furnace (Matthew 13:42, 50) and eternal fire (Matthew 25:41). Gehenna was also a designation for hell, perhaps because of the association with destruction by fire.

The origin of the concept of Gehenna may be traced to Isaiah 66:24, the shocking final verse of this book, which describes a scene in the valley of Hinnom (Gehenna), where the Tophet was located:

”And they shall go out and look at the dead bodies of the people [Israelites] who have rebelled against me [the Lord]: for their worm shall not die, their fire shall not be quenched, and they shall be an abhorrence to all flesh.”

So abhorrent is verse 24 that when Isaiah is read in the synagogue, verse 23 is repeated to prevent the Book of Isaiah from ending on such a discouraging note.

In The New Testament, when Mark alludes to hell, he quotes Isaiah 66:24: “where their worm never dies, and the fire is never quenched” (Mark 9:48)

The least noticeable of Jerusalem’s three valleys is the Tyropoeon, or Central Valley. Never very deep, today it is hardly recognizable; the accumulation of rubble over the centuries has transformed the Tyropoeon to a shallow depression. Tyropoeon is the Greek name for the Central Valley. Josephus, the first century Jewish historian, designated the Central Valley as the Tyropoeon, which he translated erroneously as the “valley of the cheesemakers.”5 Running southward through the heart of the Old City of Jerusalem, the Tyropoeon Valley divides the eastern hill (Lower City) and the Temple Mount from the western hill (Upper City).

After the city of Jerusalem expanded westward to the western hill, Wilson’s Arch (named after its discoverer Charles Wilson) served as a support for a bridge spanning the Tyropoeon Valley, connecting the Upper City to the Temple Mount. The pier of this arch, uncovered along the western wall of the Temple Mount in recent excavations, dates from the Herodian period (63 B.C.E.–70 C.E.).

From one biblical perspective, the image of Jerusalem’s three valleys is forbidding: The Kidron became a burial ground; the Hinnom, a place of punishment; and the Tyropoeon, a city dump. But from another view, that of the prophet Jeremiah, the valleys become metaphors of hope. Describing the rebuilding of Jerusalem, Jeremiah prophesied:

“The whole valley of the dead bodies and the ashes [the Hinnom Valley], and all the fields as far as the Nahal Kidron… shall be sacred to the Lord. It [Jerusalem] shall never again be uprooted or overthrown” (Jeremiah 31:40)

To understand the valleys of Jerusalem, it helps to know the different kinds of valleys encountered in the ancient Land of Israel (Eretz Yisrael). There are at least five Hebrew words designating the variety of valleys in biblical times. A large valley with water flowing intermittently is a nahal, corresponding to wadi in Arabic. Except during the rainy season, a nahal is dry. A broad, low-lying plain is an ‘emeq, meaning “depression.” An ‘emeq is not as broad as a biq‘ah, a wider, low-lying plain. A narrow gorge is a gai’. The word can be translated simply as “Valley.” […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Footnotes

See

See “Have Sodom and Gomorrah Been Found?” BAR 06:05.

Endnotes

Genesis 14:3; Numbers 34:3, 12; Deuteronomy 3:17; Joshua 3:16, 12:3, 15:2, 5, 18:19. It is also called

For additional information, see Atlas of Israel, 3rd ed. (Tel Aviv: Survey of Israel, 1985), pp. 14–15.