Debate: Where Was Herod’s Temple to Augustus?

Three sites vie for contention

022

Banias Is Still the Best Candidate

Increasingly, BAR has become a journal of record, where many excavators first publish their findings and where fellow archaeologists and interested lay people trust they can turn for readable and reliable information. It is, therefore, important that BAR authors take responsibility for providing full and reasoned accounts so as not to create the impression of certainty where none yet exists—and more importantly, not to create a “false datum” that the less well-informed will rely on and disseminate. I think that the magazine has fallen down on the job with “Reconstructing Herod’s Shrine to Augustus” (BAR 29:02).

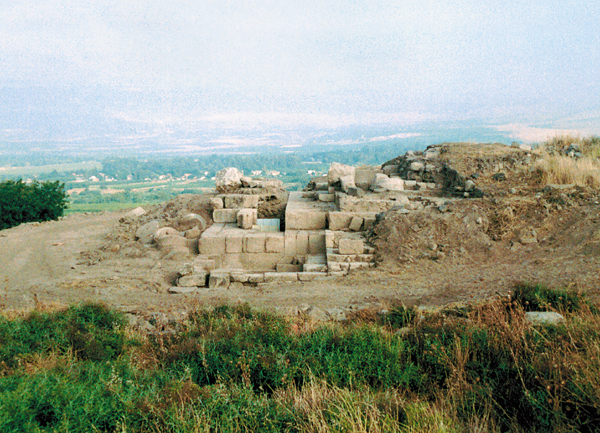

Certainly the temple that the Macalester College team has been uncovering at Omrit is spectacular. The authors—J. Andrew Overman, Jack Olive and Michael Nelson—have demonstrated that there are two phases, both imperial Roman in style, and they have provided clear and well-documented reconstructions of both structures. The argument that this monument is likely to be the temple that Herod the Great dedicated to Augustus is, however, not so well-documented and is quite a bit less certain than the article implies.

Three categories of argument are pertinent to this discussion: 1) unequivocal archaeological evidence; 2) historical testimony; and 3) related, or what might be called circumstantial, evidence. I take each in turn.

First, unequivocal archaeological evidence. What would this consist of? There is only one possibility: undisturbed strata that must predate or be contemporaneous with the construction of the earlier building, and which contain material no later than the last quarter of the first century B.C.E. (or even slightly earlier, since Herod supposedly built the Omrit building shortly after his acquisition of the Iturean principality, which came to pass after the death of the Iturean prince Zenodorus in 27 B.C.E.). By their own admission, the excavators have not yet been able to isolate such strata for the earlier temple. This is easy to understand: They have not removed any of the enormous stylobate blocks of the first structure, under which they might recover sealed material; nor have they excavated undisturbed, sealed construction fills. Their archaeological evidence therefore consists of scattered fragments of late-first-century B.C.E. pottery found in later fills. What this actually “proves” is that a bit of activity took place here, perhaps nothing more than travelers passing by.

Second, historical testimony. The authors cite briefly from Josephus—too briefly, I would say. The full text of both citations is far less compelling in favor of Omrit as the site of Herod’s temple than the authors imply. Here are both of the relevant sections of Josephus’s text in full (I have used the Loeb translations):

When, later on, through Caesar’s bounty he [Herod] received additional territory, Herod there too dedicated to him [Caesar] a temple of white marble near the sources of the Jordan, at a place called Paneion. At this spot a mountain rears its summit to an immense height aloft; at the base of the cliff is an opening into an overgrown cavern; within this, plunging down to an immeasurable depth, is a yawning chasm, enclosing a volume of still water, the bottom of which no sounding-line has been found long enough to reach. Outside and from beneath the cavern well up the springs from which, as some think, the Jordan takes its rise, but we will tell the true story of this in the sequel (The Jewish War 1.404-406).

A substantial piece of good fortune came his [Herod’s] way in addition to the earlier ones. For Zenodorus suffered a ruptured intestine, and losing a great quantity of blood in his illness, departed this life in Antioch of Syria. Caesar therefore gave his territory, which was not small, to Herod. It lay between Trachonitis and Galilee, and contained Ulatha and Paneas and the surrounding country…When he [Herod] returned home after escorting Caesar to the sea, he erected to him a very beautiful temple of white stone in the territory of Zenodorus, near the place called Paneion. In the mountains here there is a beautiful cave, and below it the earth slopes steeply to a precipitous and inaccessible depth, which is filled with 023still water, while above it there is a very high mountain. Below the cave rise the sources of the river Jordan. It was this most celebrated place that Herod further adorned with the temple which he consecrated to Caesar (Antiquities of the Jews 15.359, 363–364).

Josephus very clearly implies, indeed almost directly states, that Herod built the temple by the cave, the cliff and the spring (note especially the last line of the Antiquities passage). Of course, all of these spots are well known: the Paneion that Josephus cites is the Sanctuary of Pan at Banias (called Caesarea Philippi in the Roman period), located in and on the cave and terrace immediately below the cliff face of Mount Hermon, and below which issues forth one of the springs of the Jordan. Omrit, by contrast, is a full two miles distant from this site. Unmentioned by the authors, but certainly pertinent, is that at the time that Herod would have been building, there was no occupation or sustained activity anywhere in this area except the sanctuary terrace. Before and during the last quarter of the first century B.C.E., Omrit was simply one of many undistinguished rises in the foothills of the Golan, truly in the middle of nowhere.

Third, circumstantial evidence. Most important are the coins of Herod’s son, Herod Philip. The authors of the article correctly note that Herod Philip issued coins depicting a tetraprostyle temple, and they note as well that numismatists have long agreed that this likely depicts the temple that Herod Philip’s father, Herod the Great, built. Two points must be admitted, however: First, the coins are struck by Herod Philip, not Herod the Great; and second, numismatists have believed that the coin depicts Herod the Great’s construction because no other temple had been known to exist in the area. This association, in other words, is an excellent example of the magnetic pull of written testimony. Naturally, that is one of the many reasons that we dig: to add to, correct and/or see anew the story provided by ancient authors. Now that the Omrit excavations have discovered a temple that matches the one depicted on Herod Philip’s coins, it is up to the numismatists to decide precisely which temple is actually being shown.

A final comment, on the general historical picture. At the time that Herod the Great built his temple to Augustus, there was only one locale with evidence for activity in this region: the terrace of the Sanctury of Pan, with its enormous natural cave. That changed in 2 B.C.E., however, when Herod Philip established his new city of Caesarea Philippi at the foot of the sanctuary terrace. In antiquity a city did not comprise only a built-up center but occupied an enlarged territory that allowed new citizens access to farmland. It was typical throughout the classical world to mark the edges of a city’s territory 024with a temple, to proclaim to the traveler that one was entering a dedicated area. In fact, within sight of the temple at Omrit, immediately across the Hula Valley and up on the Galilee plateau to the west, is another Roman temple, that at Kedesh, which marks the eastern territory of Tyre.

Thus, though the temple at Omrit may have been built by Herod the Great, the case is far from secure. I believe that a more compelling argument could be made that this temple was a construction of Herod Philip, who raised this structure on the edge of his new city not only to mark his territory but also to make an architectural statement in keeping with that of his father. His coins may well depict his father’s shrine, but they may equally well depict his own impressive construction.

I believe that the tetraprostyle temple discovered at the Sanctuary of Pan at Banias, immediately in front of the cave itself, remains a likelier candidate for Herod’s temple to Augustus. Not only does this location conform precisely to the description in Josephus, but there is unequivocal archaeological testimony—in the form of an Augustan-period lamp embedded in the concrete interior of one of the building’s side walls—that this building was in fact constructed in the later first century B.C.E. The caption on page 48 of the March/April 2003 issue misstates the temple’s position at the site: It did not sit “to the left of the cave entrance,” but immediately in front of it. The cave and the terrace in front of it dominated the area and the city center of Caesarea Philippi (as indeed they still do today, even from quite a distance). The authors state that “the location of the Banias building is nothing like that of other imperial cult temples…[which are] centrally located and are part of an important and larger civic complex” (p. 49). But of course that precise argument could be raised about the building at Omrit, which was two miles away from both the sanctuary and the city center!

Neither case is conclusive. Arguments can be made for and against both the Omrit temple and the Banias temple. However, there are many more arguments in favor of the building at the Sanctuary at Banias being that of Herod the Great (archaeological, literary and historical) and more as well in favor of the building at Omrit being that of Herod Philip (largely numismatic and historical).

A journal such as BAR, which has an admirable reach and influence, should be more careful when presenting new evidence. There are responsibilities that come with growing influence. Making waves should be less important than making a case.

The authors respond:

By J. Andrew Overman, Jack Olive and Michael Nelson

Though BAR is an excellent publication, presenting the research of scholars in a popular form, it is not the only or even the primary place where archaeologists announce their findings. BAR’s unique role in stimulating archaeological conversations and alerting the public to exciting new developments in the field should not be misrepresented or diminished. After four seasons of excavation at Omrit, we have more information about the context of the site than we can readily share with BAR’s readers. The purpose of our article was to draw attention to our new discoveries and set out the case that Omrit could be the site of the temple built in the north by Herod for Augustus.

Berlin simply recites the standard interpretation of Josephus, which provides the basis for assuming that Banias was the site of Herod’s northern Augusteum. Yet if one thing is clear about Josephus, it is his ambiguity. The passages can certainly support a different reading. Besides, very few scholars would feel comfortable resting an archaeological identification on Josephus’s writings alone, but that is what one must do to assign the Augusteum to Banias. Doesn’t this constitute a “false datum”?

Berlin has ignored the core of our article and of the Omrit site, namely the temple structure itself. Its architectural style—in virtually every respect—corresponds to the Augusteum form found throughout the Roman Empire.

The real question is whether we have in fact located Herod’s northern temple to Augustus, at Banias, Omrit or elsewhere. It is difficult to piece together the finds at Banias because of the paucity of publications on the site from the last decade or so. One must rely on a single encyclopedia article and several notes in Excavations and Surveys in Israel. Nothing in this material identifies a tetraprostyle temple from the Herodian period. As of now there is no suitable candidate for Herod’s Augusteum at Banias.

There is a tetraprostyle temple at Banias, the Hadrianeum dated by excavator Zvi Ma’oz to no earlier than Trajan’s reign (98–117 A.D.). But this building had no podium, and it could not have been built in the time of Herod the Great. Even if Herod did build his Augusteum at Banias, currently there is insufficient evidence to prove it. The Omrit temple, on the other hand, looks like a real candidate for this elusive Herodian monument.

025

A Third Candidate: Another Building at Banias

By Ehud Netzer

I was very happy to read the article describing the new finds at Omrit, which is located about 3 miles southwest of Banias. But I was unhappy to see the hasty conclusions regarding the identification of the earliest temple at Omrit as the Augusteum built by Herod (which Josephus says was “in Banias”).

I am quite familiar with Omrit. About 20 years ago I assisted my colleague Gideon Foerster in conducting a survey of the site, including some limited soundings, a fact known to J. Andrew Overman and his co-directors, although this is not mentioned in their report. Omrit is, no doubt, an exciting site, and its temple is well-built and impressive. However, many questions remain open: Who built it? When? And in whose honor?

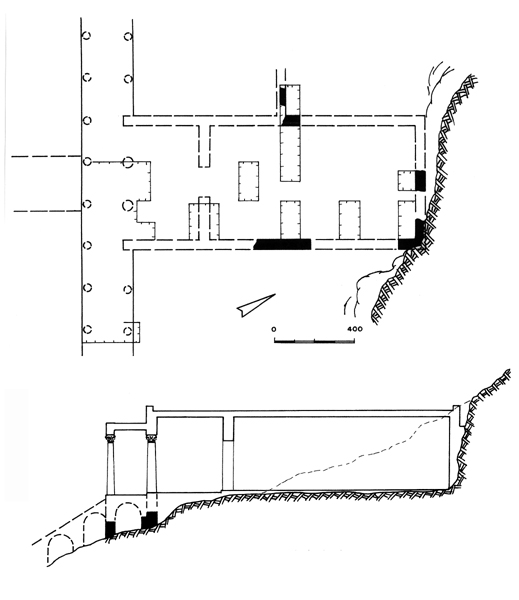

Overman and his colleagues mention the structure that was partially exposed by Zvi Ma’oz at the entrance to the famous cave at Banias. Unfortunately, they refrained, intentionally or unintentionally, from mentioning another structure at Banias, located about 100 yards west of the caves, on top of a prominent terrace. This edifice is characterized by opus reticulatum [a Roman building style in which blocks are set in a diagonal, or net-like pattern and then covered with a plaster coating]. I exposed parts of this structure during two short excavation seasons in 1977 and 1978 and concluded that this was probably Herod’s Augusteum.

During our limited excavations in the opus reticulatum structure in Banias, we uncovered parts of a large hall, 40 feet wide, partially cut out of the bedrock with the mountain behind it. The assumed length of the hall is 90 feet, but it might have been shorter, leaving enough space in front of the hall for an additional room, a sort of narthex. The hall’s floor may have originally been covered with colored stones in the opus sectile style [in which marble or other stone is cut into geometric shapes and inlaid against a different colored background]. The walls were covered with marble plates, but whether from the outset or not is hard to tell. The pottery remains were mostly late, but at least some should be dated to Herod’s time.

The walls in front of the hall (which were covered with opus reticulatum), as well as the distance between them, points toward a colonnade that once stood here. These two walls extended, on both sides, beyond the limits of the hall, making the identification of the hall’s facade difficult. In any event, one might assume that the approach to the building was via a flight of steps, overcoming the rock scarp rising in front of the hall.

A major issue regarding this building is whether it had a specific function or was part of a larger complex. I tend toward the first option, and believe the remains are those of Herod’s Temple (Augusteum) in Banias.

As a reaction to an article by Ma’oz,a I published two short notes that included, for the first time, a drawing of this structure, partially restored. Recently I visited Banias in order to study the possibility that this tentative temple also included a colonnaded forecourt. It might have, but additional excavations are needed to resolve the issue.

In contrast to Omrit, the attribution of the building in Banias to Herod is without doubt and is based on our knowledge of all three Herodian structures that include opus reticulatum (incidentally, I initiated the excavations at all three). All the structures were built by a team sent from Rome to Judea, apparently following the visit of Marcus Agrippa there in 15 B.C.E.

BAR’s article on Omrit focuses on one word in Josephus regarding the location of Herod’s temple to Augustus being “near the place called Paneion.” But when one looks at the whole quotation (including the parallel one in The Jewish War), it will be hard to convince any scholar that Josephus did not refer to Banias. On the other hand, a careful study of the historical data, as well as the results of recent excavations at Banias (especially the remains of a palace excavated by Vassilios Tzaferis) point to other possible builders of the Omrit temple. The descendants of Herod the Great, for example, ruled here for many years and were responsible for much construction. In any event, Josephus refers to only one building that Herod built in Banias—a temple—and in my opinion it must have been the opus reticulatum one.

Banias Is Still the Best Candidate

By Andrea M. Berlin

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.