Past Perfect: In Pursuit of Minoan Crete

American archaeologist Harriet Boyd Hawes ventures into the masculine world of Mediterranean archaeology.

028

Long overshadowed by her colleague Sir Arthur Evans (1851–1941), the discoverer of ancient Minoan civilization, Harriet Boyd Hawes was the first woman to direct a major dig in the Aegean. Born in Boston in 1871, she was educated at Smith College, where she became fascinated with the ancient world after hearing a lecture by the British novelist and Egyptologist Amelia Edwards. Boyd continued her studies at the American School of Classical Studies in Athens, but she became frustrated by the school’s refusal to let her do fieldwork. In 1897 she joined the Red Cross to work as a volunteer nurse during a war between Greece and Turkey. In 1900, after meeting Arthur Evans—whose excavations at Knossos, on Crete, were inaugurated that very year—Boyd traveled to Crete to find a dig of her own. She briefly excavated a first-millennium B.C. site in Kavousi, a village on the island’s northeast coast, and then took a position teaching Greek archaeology at Smith College. By 1901, however, she was back in Crete, surveying the area around Kavousi and hoping to find an older site. On a hill overlooking the Gulf of Mirabello, she came across traces of an ancient settlement, which she decided to investigate. During three excavation seasons (1901, 1903 and 1904), Boyd uncovered 2 acres of this mid-second-millennium B.C. site, including streets, houses, a small palace, a shrine and workshops (the accompanying excerpt is from her excavation report to the American Exploration Society). On returning to the U.S., she went on a national lecture tour, married the British anthropologist Charles Henry Hawes and taught pre-Christian art at Wellesley College. Harriet Boyd Hawes died in 1945.

029

Miss Wheeler [one of Harriet Boyd’s classmates at Smith College] and I landed in Crete April 7th [1901] … Much progress had been made at Knossos and Phaestos, and such success in the Mycenaean and pre-Mycenaean field or, to use more up-to-date nomenclature, the “Minoan” field, increased my longing to find something belonging to this Golden Age of Cretan history.

For two weeks our party … suffered some hardships, especially during thirty-six hours of incessant rain that caused serious floods in eastern Crete, wrecked a hut near us, loosened our own walls, and poured into the hut we used for a kitchen … On holidays and on days when the ground was too wet for digging we rode up and down Kavousi plain and the neighboring coast hills seeking for the Bronze Age settlement which I was convinced lay in these lowlands somewhere near the sea. It was discouraging work, for my eyes soon came to see walls and the tops of beehive tombs in every chance grouping of stones … rumor of our search reached the ear of George Perakis, peasant antiquarian of Vasiliki, a village three miles west of Kavousi, and he sent word by the schoolmaster that he could guide us to a hill three-quarters of a mile west of Pachyammos, close to the sea, where there were broken bits of pottery and old walls. Moreover he sent an excellent seal-stone picked up near the hill, and although seal-stones are not good evidence—being easily carried from place to place—his story was too interesting to pass unheeded. Accordingly, on May 19th, Miss Wheeler and I rode to the spot, found one or two sherds with curvilinear patterns … saw stones in lines which might prove to be parts of walls (never more than one course visible), and determined to put our force of thirty men at work there the following day. Three days later we had dug nineteen trial pits and had opened houses, were following paved roads, 030and were in possession of enough vases and sherds with cuttle-fish, plant, and spiral designs, as well as bronze tools, seal impressions, stone vases, etc., to make it certain that we had a Bronze Age settlement of some importance. Accordingly I sent the following cablegram to the American Exploration Society: … “Discovered Gournia—Mycenaean site, street, houses, pottery, bronzes, stone jars” …

Gournia is a name given by the peasants of the district to a basin opening north on the Gulf of Mirabello, and enclosed on the other three sides by foothills which rise west of the narrow strip of isthmus … Our town, which until we know its ancient name must be called by the modern designation “Gournia,” covered not only the middle of the ridge, where it rises two hundred feet above sea-level, one-quarter of a mile back from the Gulf, but extended across the eastern valley up the hills to the east and northeast, so that the acropolis was the centre of a settlement of considerable size …

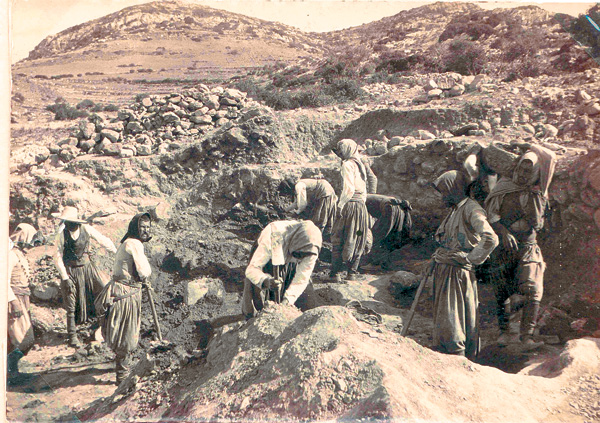

At the beginning of excavations only a few stones showed above the surface and many houses were entirely hidden, being discovered in the course of digging by workmen who, following the roads, came upon their thresholds … On the top of the hill where denudation is constant, there was but a scant covering of earth over the native rock; here some of the best objects of bronze and terra-cotta were found within 50 cm. of the surface … On the sides of the hill where earth accumulates we were often obliged to dig four or five metres before reaching virgin soil, live rock, beaten floor, or stone paving, as the case might be. Excavations have been carried on at Gournia through two campaigns, May 20 to July 2, 1901, and March 30 to June 6, 1903, with a force of 100 to 110 workmen and about a dozen girls who wash potsherds … the entire area cleared may be roughly computed as 2 acres, the top of the acropolis as about 1 acre, and the Palace as 1/3 of an acre. Thirty-six houses and parts of several others are uncovered …

Special mention should be made of the Palace … On the west side are four storerooms communicating with a flight of steps, and three long, narrow magazines opening on a common corridor that correspond, though on a much smaller scale, to those at Knossos and Phaestos … West of the storerooms the road widens into a small plateia, of which we have not yet determined the western boundary. South of this is a space, having a cement pavement, which seems to be part of the Palace, possibly a loggia, in which case the west road continuing south must have formed a covered way within the Palace. From the southern end of this covered way a paved passage leads 031east, while the road continues southwest. The eastern passage ends in three steps [leading to] … a large open Court, which seems to answer to the West Court of Knossos, and may have served as a market-place for the town …

Beginning March 30, 1903 at this portico, from which we had removed our last loads of earth in 1901, we dug northward into the centre and, as it proved, the most interesting part of the Palace [an Inner Court that opens onto a square Hall] … In the southeast corner of the Hall is a rectangular recess with a stone bench around three sides and a round base for a column that must have supported an architrave across the open side. Here we may suppose the Prince sat to receive his friends and to dispense justice. It is a semipublic part of the Palace corresponding to the Throne Room at Knossos. No doubt the private rooms were on the second story; to them a narrow flight of stairs led from the northeast corner of the Hall … At first we were astonished to find, immediately adjoining this important Hall on the north, one square and two oblong storerooms, the square room containing twelve huge pithoi, one of which is still perfect; but reflection shows that this arrangement is a good one, for if the Hall was semipublic and was an eating-hall for retainers it would be convenient to have “cellar” and pantry at hand …

Of the shrine which lies in the centre of the town, approached by a well-worn road of its own, I shall say very little, as it opens up too large a subject for discussion here. Not imposing as a piece of architecture, it is yet of unique importance as being the first “Mycenaean” or “Minoan” shrine discovered intact … our shrine has suffered much from the forces of Nature. A wild carob tree growing within its bounds had partly destroyed and partly saved its contents, of which the more noteworthy are a low earthen table, covered with a thin coating of plaster, which stands on three legs and possibly served as an altar, four cultus vases bearing symbols of Minoan worship, the disc, consecrated horns and double-headed axe of Zeus, a terra-cotta female idol entwined with a snake, two heads of the same type as the idol, several small clay doves and serpents’ heads.

From Harriet Boyd Hawes’s report to the American Expedition Society, Philadelphia, Wells-Houston-Cramp Expeditions, courtesy of the University of Pennsylvania Museum.

Long overshadowed by her colleague Sir Arthur Evans (1851–1941), the discoverer of ancient Minoan civilization, Harriet Boyd Hawes was the first woman to direct a major dig in the Aegean. Born in Boston in 1871, she was educated at Smith College, where she became fascinated with the ancient world after hearing a lecture by the British novelist and Egyptologist Amelia Edwards. Boyd continued her studies at the American School of Classical Studies in Athens, but she became frustrated by the school’s refusal to let her do fieldwork. In 1897 she joined the Red Cross to work as a volunteer […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.