Although we have no Ammonite, Moabite or Edomite Bible, a growing wealth of archaeological and epigraphic evidence from Jordan substantiates the existence of these Iron Age kingdoms closest to Israel and Judah, just as presented in the Hebrew Bible. My work as a historian of Israelite religion has led me through an ongoing firsthand exploration of this material east of the Jordan River, most recently, a larger-than-life statue of an Ammonite king, the first Iron Age statue on this scale ever discovered east or west of the Jordan. These discoveries in Jordan reveal Iron Age kingdoms that, like Israel and Judah, formed on the basis of tribal structures, named their own kings and worshiped their own national gods.

We know them in the Bible and increasingly in archaeology as Ammon, Moab and Edom.

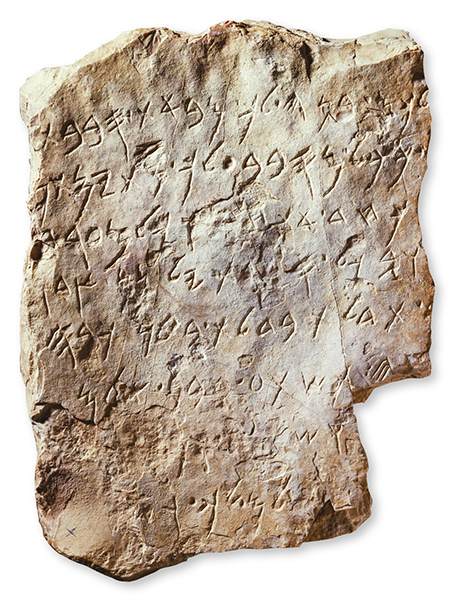

The Hebrew Bible’s usual designation of the Ammonites as “the children of Ammon” (bĕnê ‘Ammôn, e.g., 1 Kings 11:7, 33) matches the threefold reference in the Ammonite Tell Siran Inscription, “the king of the children of Ammon” (mlk bn ‘mn; c. 600 B.C.E.; cf. mlk bny ‘mwn, Jeremiah 27:3).a This kin-based formulation of political identity reflects a tribal social makeup and kingdom organization analogous to that of ancient Israel, “the children of Israel” (bĕnê yiśrā’ēl).

The Ammonite heartland comprised the north-central Transjordanian Plateau encircled by the upper Jabbok (modern Wadi Zarqa), within a 12.5-mile radius of its capital at the headwaters of the Jabbok, Rabbah, “the Great (City),” or Rabbat bĕnê ‘Ammōn, “the Great (City) of the Children of Ammon” (2 Samuel 12:26, 29), the modern Amman Citadel (Jabal al-Qal‘a).

Archaeological excavations at the Amman Citadel over the past five decades have unearthed monumental architectural remains from the Iron Age II (1000–580 B.C.E.), including portions of the city’s defense walls and water system. The excavations also exposed a large building complex resembling an Assyrian palace on the lower terrace. Running beneath a later Roman-period temple to Hercules, still visible today, are remains of an Iron Age megalithic building of limestone boulders containing several votive figurines, possibly the Ammonite kingdom’s main temple to its leading deity.b 1

References to building and architectural terms in the first-person speech of a king or god make up the apparent focus of the famous Amman Citadel Inscription, dating to the late ninth century B.C.E.c The inscription begins with a partially restored mention of Milcom, regularly named in the Hebrew Bible as the leading god of the Ammonites (see, e.g., 1 Kings 11:5, 33; 2 Kings 23:13). Milcom is also invoked in personal names, including the name of a royal official—“Milkom’ur servant of Baalyasha”—on a clay seal impression from excavations at Tall al-‘Umayri, dating to c. 600 B.C.E. Baalyasha is identified with the Ammonite King Baalis mentioned in Jeremiah 40:14. Just as the worship of Yahweh set Israelites apart from other peoples during the Iron Age II, so did the Ammonites’ worship of Milcom distinguish them from their closest neighbors and rivals.

The Ammonite god Milcom receives artistic representation in a series of stern-faced (usually bearded) stone statues and sculpted heads from Amman wearing a variant of the Egyptian atef crown, an emblem depicting deities in Syria-Palestine since the second millennium B.C.E.2 A collection of double-faced female sculpted heads in limestone from the Amman Citadel might represent a goddess or group of Ammonite goddesses within an architectural design.

Ammonite stone sculpture also includes depictions of human royal figures. For example, the inscribed limestone statuette of Yarḥ-‘Azar is identified as the grandson of Shanib, perhaps the Ammonite king mentioned by Tiglath-pileser III around 734 B.C.E.3 And now we can include a monumental basalt statue of an Ammonite king preserved to more than 6.5 feet in height and excavated in 2010 in front of the Roman theater in downtown Amman.4 These two statues portray human royal figures not wearing a crown but, rather, wearing a headband or diadem with the head uncovered. Both figures hold a drooping lotus flower, also of Egyptian derivation, representing a deceased ruler in the art of Syria-Palestine. This larger-than-life image of an Iron Age king is the first statue of this size ever discovered east or west of the Jordan.

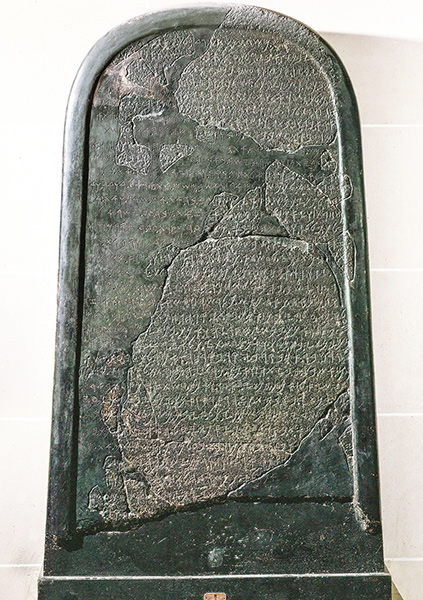

Turning to Moab, the famous Mesha Stele (c. 840 B.C.E.) presents the longest Iron Age epigraphic text surviving from the southern Levant. The basalt stone monument once stood in Mesha’s capital, Dibon (modern Dhiban), marking a worship place the king built in honor of Moab’s god Chemosh, whom Mesha credits in the inscription with his achievements of territorial expansion, building cities and defeating enemies. The principal enemy in the inscription is the northern Israelite kingdom previously ruled by Omri and “his son.”d According to Mesha, Moab had suffered in the past under these Israelite kings because Moab’s god Chemosh “was angry with his land.” In describing the lands he rules and conquers, Mesha reveals a kin-based society, invoking his father, Chemosh[yat],5 who ruled before him, identifying himself by the people-group designation “Daybonite,” and discussing “the men of Gad,” doubtless the same Gad figuring as an Israelite tribe in the Hebrew Bible (Genesis 49:19; Deuteronomy 33:20–21; etc.). Though built on this tribal basis, Mesha’s kingdom is identified primarily by geography, namely, the ancient country of Moab appearing in Egyptian texts centuries earlier and united from territorial segments through warfare in the name of the god Chemosh.6 Like ancient Israel, Moab’s practices of ritual warfare included ḥerem, the execution of whole populations in devotion to the vanquishing deity (Deuteronomy 13:15; 20:16–17; Joshua 6:17–19; etc.).

The Mesha Stele views Moab and Israel as analogous kingdoms in irreconcilable opposition: each with its own territory, people, king, royal lineage (Chemoshyat and Mesha vs. Omri and “his son”) and god (Chemosh vs. Yahweh). These oppositions resolved at the boundaries through warfare, conquest and ḥerem.7

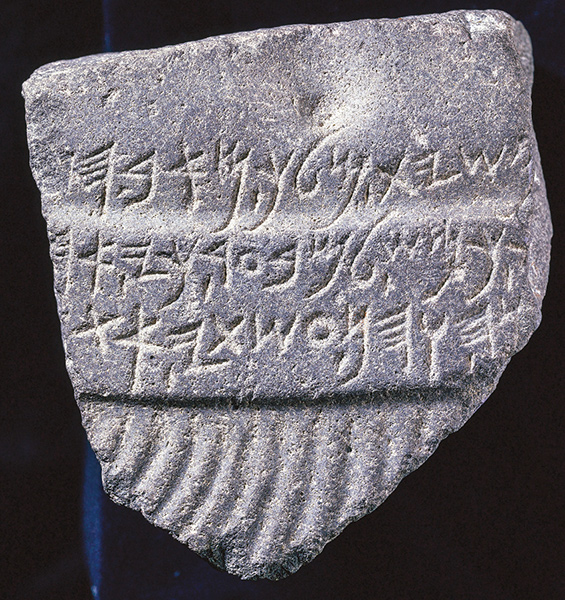

The full name of Mesha’s father in the Mesha Stele (kmš[yt]) is supplemented in the Kerak Inscription fragment, another monumental inscription on stone in the same Moabite language, with a similar script of comparable date, that begins with the same formulary naming of the “King of Moab.”8

These and other Moabite inscriptions, monumental architecture and royal sculpture indicate a Moabite kingdom spanning territory both north and south of the Arnon River.

Like the Ammonites, the Moabites developed their own sculptural forms drawing on broader ancient Near Eastern artistic traditions, portraying divine support of royal power. Monumental basalt sculpture from the land of Moab includes several impressive examples, most prominently the stele from the Iron Age site of Balua‘, which guarded southern access to the Arnon River from the Kerak Plateau. The Balua‘ Stele (which recent scholarship has dated variously between 1400 and 800 B.C.E.) displays a section of undeciphered writing and a relief scene showing an Egyptian-style god and goddess conferring emblems of authority on a human leader wearing a Shasu headdress, an emblem recognized from Egyptian artistic depictions. The Egyptian term Shasu refers to mobile pastoral peoples with a kin-based social and political structure, often in connection with southern Transjordan in Egyptian texts of the 19th Dynasty (13th–early 12th centuries B.C.E.).9 At the Arnon River crossing, the Balua‘ Stele reflects a vision of divinely sanctioned kingship on the basis of tribal political authority, suggesting formative dynamics for the Iron Age II Kingdom of Moab.

The Shihan (or Rujm el-Abd) relief discovered just a few miles northwest of Balau‘ shows a warrior figure wielding a spear and reflects Egyptian artistic motifs.10 A basalt orthostat from Kerak in the form of a lion resembles Neo-Hittite and Aramean palace and temple traditions in Syria.11

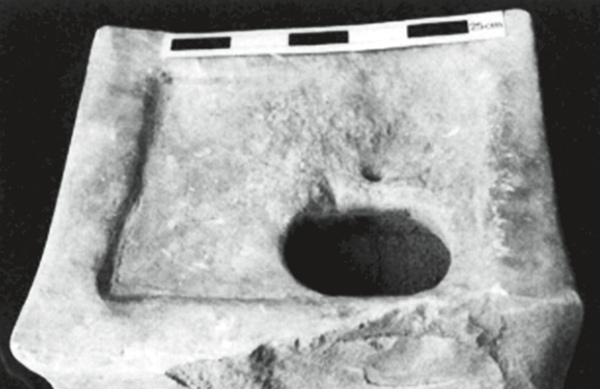

Recent archaeological discoveries from Moab have added important religious evidence for the Iron Age. These include a plethora of limestone altars from the fortified outpost of Khirbat al-Mudayna (Mudeiniyeh).12 A small temple just inside the town’s six-chambered fortified gate yielded three limestone altars ranging in height from c. 19.5 to 37.5 inches, one of which is a rectangular shaft altar for pouring libations (as indicated by a drain hole).13

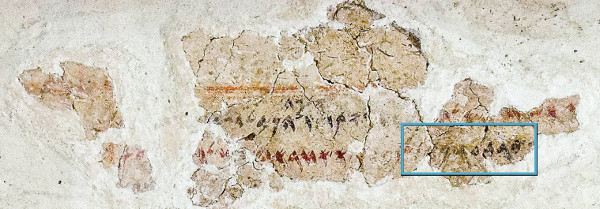

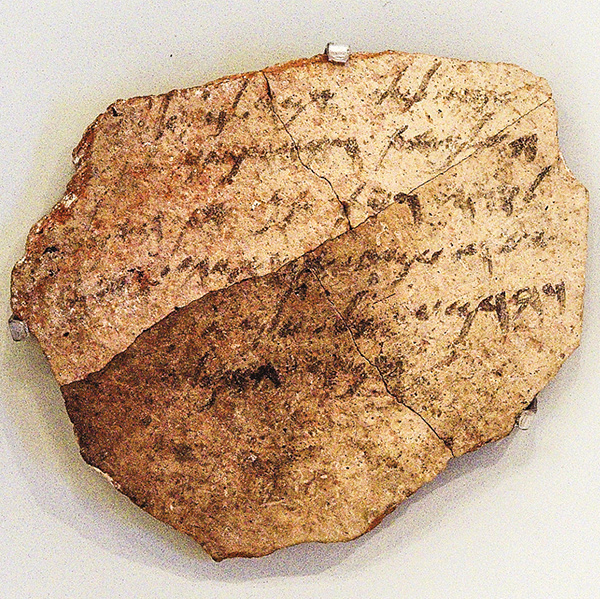

The archaeological site Khirbat ‘Aṭaruz about 7 miles east of the Dead Sea has been identified with Ataroth, which is mentioned in the Mesha Stele as a town of Israelite Gad that the king of Moab conquered and from which he pillaged an important cultic item (“the altar hearth [?] of its DWD”). Excavations at ‘Aṭaruz have revealed an elaborate temple complex yielding spectacular cultic artifacts, including a ceramic bull statue and a multi-story shrine model with male figurines attached.14 The ‘Aṭaruz temple complex has also yielded a cylindrical sculpted stone pedestal, ostensibly part of an altar or other cultic object, bearing an inscription dated to the ninth century B.C.E.15

Like Moab, Edom figures primarily as a territorial designation in Late Bronze Age Egyptian texts and in the Hebrew Bible (e.g., Genesis 32:4; 1 Kings 11:14–16). As reflected in Biblical etiologies connecting to Esau (Genesis 25:25, 30), Edom refers to the mountainous “red” land of sandstone, granite and soil east of the Arabah, extending south of the Zered (modern Wadi Hasa) to the Gulf of Aqaba. Along with the closely associated place-name Seir (cf. Genesis 36:8–9, 21), Edom appears in Egyptian texts with frequent associations to the tent-dwelling mobile pastoralists designated Shasu.16 These Egyptian references to Edom’s Shasu peoples may provide the textual background for the kin-based population known from the enormous cemetery labeled Wadi Fidan 40 at the entrance to the Faynan wadi system in the northeast Arabah.17

The god Qaus/Qos is by far the most frequently invoked deity in Edomite personal names from various inscriptions. The role of Qos as Edom’s leading deity receives further corroboration from the names of Edomite kings mentioned in Assyrian sources.18 A royal seal impression of “Qaus-ga[bri], King of E[dom]” (qws g[br]/ mlk ’[dm]) was recovered from a palace on Umm el-Biyara in Petra.19 The deity’s name was also found on a vessel sherd from Busayra (Buseira), whose impressive architecture indicates the site’s status as the Edomite royal city by the late eighth century B.C.E.20 At Tell el-Kheleifeh near the Gulf of Aqaba shore, multiple impressions come from the seal of a royal official, “Qos‘anal, servant of the king” (lqws‘nl / ‘bd hmlk,).21

The Hebrew Bible’s mysterious silence regarding Qos, or any Edomite deity for that matter,22 along with Yahweh’s associations with the territory of Edom and its vicinity in Biblical poetry (Judges 5:4; Habakkuk 3:3, 7) and the Biblical traditions of Edom’s “brotherhood,” may reflect a possible close connection—if not an original equation—between Israelite Yahweh and Edomite Qos.

The best-preserved candidates for Edomite worship places have been excavated not in Edom proper but west of the Arabah in the southeastern Negev, where Qos is invoked during the late seventh or early sixth century B.C.E., in an epistolary blessing in the Ḥorvat ‘Uza ostracon inscription and in dedication inscriptions engraved on vessel rims at the sanctuary site of Ḥorvat Qitmit.23 It is at Qitmit that some scholars recognize the most abundant assemblage of evidence for Edomite worship, including Edomite pottery, ceramic cylindrical statuettes and stands, figurines and cultic vessels.24 At Ein Hazeva in the northwest Arabah, a similar assemblage of ceramic statues and other objects was excavated from a pit outside the Iron II fortress.25 Renewed excavations at Busayra (Buseira) by Benjamin W. Porter hold promise for new discoveries on religion in Edom proper.

How do these kingdoms compare with Israel and Judah on the other side of the Jordan River? As we have seen, Israel, Judah and these Transjordanian kingdoms are similar in many respects. Each had its own national god. Each was a tribal kingdom. Each battled against the others over territory and boundaries. Israel even claimed territory east of the Jordan.

Yet from Israel we do not have a single piece of monumental sculpture comparable to those from Ammon and Moab. When it comes to inscriptions, the disparity is even more dramatic. The great inscriptions confirming the history (even the very existence) of Israel and Judah and shedding light on national (and international) religious life come from kings and kingdoms other than Judah and Israel—most important, the Mesha Stele, the Tel Dan Stele and the Balaam inscription from Deir ‘Alla.

Go to the archaeological section of the Israel Museum in Jerusalem. There is not a single piece of impressive Iron Age sculpture from Judah or Israel. Even more surprising—not a single lengthy Hebrew inscription from this period exists.

Why is this the case? Is there some cultural reason that Israel has not produced great visual Iron Age art? And why aren’t there long inscriptions? Is it simply the luck of the archaeological draw? Or is there some deeper cultural or historical distinction between the kingdoms west and east of the Jordan? Could it have something to do with the fact that we also have no Ammonite, Moabite or Edomite Bible?

MLA Citation

Footnotes

P. Kyle McCarter Jr., Ancient Inscriptions: Voices from the Biblical World (Washington, DC: Biblical Archaeology Society, 1996), pp. 98–99.

Timothy P. Harrison, “Rabbath of the Ammonites,” Archaeology Odyssey 05:02.

P. Kyle McCarter Jr., “A Voice of Their Own: Ammonite Inscriptions,” Archaeology Odyssey 05:02.

P.M. Michèle Daviau and Paul-Eugène Dion, “Moab Comes to Life,” BAR 28:01; Siegfried H. Horn, “Why the Moabite Stone Was Blown to Pieces,” BAR 12:03.

Endnotes

Rudolph H. Dornemann, “The Beginning of the Iron Age in Transjordan,” Studies in the History and Archaeology of Jordan 1 (1982), pp. 135–140; F. Zayadine, J.-B. Humbert and M. Najjar, “The 1988 Excavations on the Citadel of Amman—Lower Terrace, Area A,” Annual of the Department of Antiquities of Jordan 33 (1989), pp. 357–363 and plates 50–52; Ahmed Momani and Anthi Koutsoukou, “The 1993 Excavations,” in A. Koutsoukou et al., eds., The Great Temple of Amman: The Excavations (Amman: American Center of Oriental Research, 1997), pp. 157–171; Sahar Mansour, “Preliminary Report of the Excavations at Jabal al-Qal‘a (Lower Terrace): The Iron Age Walls,” Annual of the Department of Antiquities of Jordan 46 (2002), pp. 141–150.

Joel S. Burnett, “Egyptianizing Elements in Ammorite Stone Statuary: The Atef Crown and Lotus,” in Oskar Kaelin, ed., 9 ICAANE: Proceedings of the 9th International Congress on the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East (June 9–13, 2014, University of Basil), vol. 1, Traveling Images (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 2016), pp. 57–71.

James B. Pritchard, The Ancient Near Eastern Texts (ANET), 3rd ed. (Princeton: Princeton Univ. Press, 2010), p. 282.

Joel S. Burnett and Romel Gharib, “An Iron Age Basalt Statue from the Amman Theatre Area,” Annual of the Department of Antiquities of Jordan 58 (2014).

The name of Mesha’s father in line 1 is partially restored from the Kerak Inscription fragment, another roughly contemporary monumental inscription on basalt that preserves the last part of a name ]šyt as king of Moab.

This geographically “segmented” kingdom model represented by Moab has been identified by Bruce Routledge, Moab in the Iron Age: Hegemony, Polity, Archaeology (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004). For the Egyptian texts of Ramses II mentioning Moab, see Kenneth A. Kitchen, “The Egyptian Evidence on Ancient Jordan,” in P. Bienkowski, ed., Early Edom and Moab: The Beginning of the Iron Age in Southern Jordan (Sheffield: Collis, 1992), pp. 27–28.

The most recent study suggests that the black stone may be granodiorite, rather than basalt, and may have once belonged to a statue. See Heather Dana Davis Parker and Ashley Fiutko Arico, “A Moabite-Inscribed Statue Fragment from Kerak: Egyptian Parallels,” BASOR 373 (May 2015), pp. 105–120.

Routledge, Moab in the Iron Age, pp. 178–179; Fawzi Zayadine, “Sculpture in Ancient Jordan: Treasures from an Ancient Land,” in P. Bienkowski, ed., Early Edom and Moab: The Beginning of the Iron Age in Southern Jordan (Sheffield: Collis, 1992), pp. 35–36.

P.M. Michèle Daviau, “Stone Altars Large and Small: The Iron Age Altars from Hirbet el-Mudēyine (Jordan),” in S. Bickel et al., eds., Bilder als Quellen/Images as Sources: Studies on Ancient Near Eastern Artefacts and the Bible Inspired by the Work of Othmar Keel, Orbis Biblicus et Orientalis Special Volume (Fribourg/Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2007), pp. 125–150.

P.M. Michèle Daviau and Margreet Steiner, “A Moabite Sanctuary at Khirbat Al-Mudayna,” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 320 (2000), pp. 1–21, especially pp. 8–14; Paul E. Dion and P.M. Michèle Daviau, “An Inscribed Incense Altar of Iron Age II at Hirbet el-Mudēyine (Jordan),” Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins 116 (2000), pp. 1–13.

Chang-Ho Ji, “The Early Iron Age II Temple at Hirbet ’Aṭārūs and Its Architecture and Selected Cultic Objects,” in Jens Kamlah, ed., Temple Building and Temple Cult: Architecture and Cultic Paraphernalia of Temples in the Levant (2.–1. Mill. B.C.E.), Abhandlungen des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins 41 (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 2012), pp. 203–222 and plates 46–49.

Chang-Ho Ji, “Architectural and Stratigraphic Context of the ‘Ataruz Inscription Column” (Presentation at the ASOR Annual Meeting, Chicago, Illinois, November 16, 2012); Christopher A. Rollston, “The New ‘Ataruz Inscription: Late Ninth Century Epigraphic Evidence for the Moabite Scribal Apparatus” (Presentations at the ASOR Annual Meeting, Chicago, Illinois, November 16, 2012).

Thomas E. Levy, Mohammad Najjar and Ben-Yosef, New Insights into the Iron Age Archaeology of Edom, Southern Jordan, 2 vols. (Los Angeles: The Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press, 2014).

Qausmalak by Tiglath-pileser III (c. 734 B.C.E.) and Qausgabri by Sennacherib and Ashurbanipal (early seventh century B.C.E.).

See the cautious comments of David Vanderhooft, “The Edomite Dialect and Script: A Review of the Evidence,” in Diana Vikander Edelman, ed., You Shall Not Abhor an Edomite for He Is Your Brother: Edom and Seir in History and Tradition, Archaeology and Biblical Studies 3 (Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1995), p. 151. Qausgabri of Edom is named among those supplying labor and materials for Esarhaddon’s building projects in Nineveh (c. 673 B.C.E.; ANET 291) and providing assistance in Ashurbanipal’s wars against Egypt (beginning 669 or 667 B.C.E.; ANET 294).

Piotr Bienkowski, Crystal Bennett and Marta Balla, Busayra: Excavations by Crystal-M. Bennett 1971–1980, Monographs in Archaeology 13 (Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, 2002).

The only exception is the personal name Barqos, “Qos gleamed forth” (Ezra 2:53; Nehemiah 7:55). The name Kushaiah (1 Chronicles 15:17) has the variant form Kishi in 1 Chronicles 6:29 (6:44, English) and in any case involves a spelling with shin that is never used for Qos in other texts. See E.A. Knauf, “Qôs,” in Karel van der Toorn, Bob Becking and Pieter W. van der Horst, eds., Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible, 2nd ed. (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1999), p. 674.

Itzhaq Beit-Arieh and B. Cresson, “An Edomite Ostracon from Horvat ‘Uza,” Tel Aviv 12 (1985), pp. 96–100; Itzhaq Beit-Arieh, Horvat Qitmit: An Edomite Shrine in the Biblical Negev, Monograph Series of the Sonia and Marco Nadler Institute of Archaeology 11 (Tel Aviv: Institute of Archaeology, 1995).

Beit-Arieh, “An Edomite Ostracon”; J. Andrew Dearman, “Edomite Religion. A Survey and an Examination of Some Recent Contributions,” in Diana Vikander Edelman, ed., You Shall Not Abhor an Edomite for He Is Your Brother, pp. 121–131; Pirhiya Beck, “Horvat Qitmit Revisited via ‘En Hazeva,” Tel Aviv 23 (1996), pp. 102–114; André Lemaire, “Edom and the Edomites,” in André Lemaire and Baruch Halpern, eds., The Books of the Kings: Sources, Compositions, Historiography and Reception, Supplements to Vetus Testamentum 129 (Leiden/Boston: Brill, 2010), pp. 225–243.

Rudolph Cohen and Yigal Yisrael, “The Iron Age Fortresses at En Haseva,” The Biblical Archaeologist 58 (1995), pp. 223–235; P.M. Michèle Daviau, “Diversity in the Cultic Setting: Temples and Shrines in Central Jordan and the Negev,” in Jens Kamlah, ed., Temple Building and Temple Cult: Architecture and Cultic Paraphernalia of Temples in the Levant (2.–1. Mill. B.C.E.), Abhandlungen des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins 41 (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, 2012), pp. 435–458 and plates 63–64.