Found After 1400 Years—The Magnificent Nea

032

Byzantine Jerusalem was Christian Jerusalem—par excellence. The Byzantine era began when the Emperor Constantine—soon to convert to Christianity—became master of Palestine in 324 A.D. It did not end in Jerusalem until the Patriarch Sophronius surrendered the city to the Moslem caliph Omar in the spring of 638.

The Byzantine period was a prosperous one, and Jerusalem shared in this prosperity. Marked by intensive building activity, this period saw almost every inch of the city covered with construction of one kind or another. After Constantine decided to make Jerusalem the Holy City of Christendom, gifts and pilgrims followed. Gradually Jerusalem was transformed into a city of churches and monasteries, hospices and asylums for pilgrims—as depicted on the mid-6th century Madaba map.

Byzantine building activity in Jerusalem can be divided into three major stages.

The first began with the visit to Jerusalem of Constantine’s mother, Helena, in 326. The most important monument of this period is the Church of the Holy Sepulchre (See J.-P. B. Ross, “The Evolution of a Church—Jerusalem’s Holy Sepulchre,” BAR 02:03).

The second stage of Byzantine building activity is associated with another woman—the Empress Eudocia, wife of Theodosius II. After separating from her husband in 443–444, she lived in Jerusalem until her death in 460, Among other activities, Eudocia repaired and enlarged the city wall, founded a home for the aged and established a church dedicated to the first martyr, Saint Stephen.

In 529 a Samaritan revolt devastated the vicinity of Jerusalem. Many of the city’s churches were destroyed. The Emperor Justinian (527–565) undertook to remedy this, and with him is associated the third great building period of the Byzantine Era.

Among a number of new churches which he built, the most magnificent was the famed Nea or New Church dedicated to the Virgin Mary. The church was consecrated on November 20, 543. It has justly been described as the jewel of Byzantine Jerusalem.

A major monument on the Madaba map, the Nea is placed at the southern end of the Cardo, Jerusalem’s major north-south thoroughfare (see photograph of Madaba map in “The Ancient Cardo Is Discovered In Jerusalem,” BAR 02:04). Only the Church of the Holy Sepulchre exceeded it in importance as a Christian shrine.

Procopius of Caesarea, who served as Justinian’s court historian, begins his glowing description of the Nea like this: “In Jerusalem [the Emperor Justinian] dedicated to the Mother of God a shrine with which no other can be compared. This is called by the natives the ‘New Church’.”

Procopius’ description of the site, plan and construction of the church has been the foremost—and the most tantalizing—piece of evidence in a decades-long search for the Nea that has exercised many a distinguished archaeologist. The past few years have seen the dramatic finale, with the unearthing of vestiges of the once-magnificent edifice, one of the largest shrines in Christian history, from the oblivion of over fourteen centuries.

Among early scholars, some identified the “Nea” with the silver-domed mosque of El-Aqsa, which stands on the Temple Mount. El-Aqsa, like the Nea, is built in a basilica style. The Omayyad Caliph El-033Walid I (705–715), who constructed El-Aqsa, transformed the church of St. John the Baptist in Damascus into a mosque, so it was thought that perhaps he transformed the Nea into El-Aqsa. However, there is no indication in literary sources that the Moslems transformed any Jerusalem churches into mosques; nor is there any suggestion that the Christians built any structure on the Temple Mount. On the contrary, according to literary sources, the Temple Mount was left untouched throughout the centuries of Byzantine rule. Moreover, the idea that the Nea was transformed into the El-Aqsa is altogether incompatible with Procopius’ siting of the church, as well as the location given by early Christian pilgrims who describe the Nea as standing west of the southwest corner of the Temple Mount on the eastern summit of the Upper City.

At the turn of the present century, in the course of construction work for a Sephardi Hospital, ancient remains were uncovered about a hundred yards west of the Temple Mount. Closer investigation by the Dominican Father Hugo Vincent, a renowned Jerusalem scholar, revealed the ruins of walls and mosaic floors. These he described in an article in the Order’s archaeological journal Revue Biblique (No. XI 1914), suggesting that they formed part of the cherished Nea Church. However, similar finds in the area and elsewhere in Jerusalem indicated that all belonged to private dwellings of that period, a striking reminder of the high standard of living in Byzantine Jerusalem.

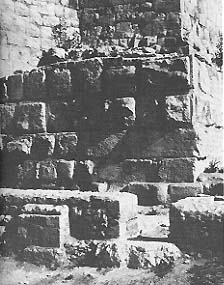

Hopes for a successful outcome in the search for the Nea rose when, after the Six-Day War, Professor Nachman Avigad’s team began to dig below the surface of the Old City’s Jewish Quarter. There they uncovered a section of a wall of massive masonry over 40 feet long, dating from the late Byzantine period. The wall was over 20 feet thick, built on bedrock, with very large stones on the outside and smaller stones on the inside. The wall contained an apse pointing east, the orientation of almost all ancient churches. Based on this apse, the massiveness of the wall, Procopius’ description of the Nea, and the location of the Church on the Madaba map, Avigad quite correctly concluded that he had found the foundations of the eastern wall of the Nea. Here was the first visible evidence of the ancient shrine. Based on the large number of 034known Byzantine churches, Avigad also concluded that this eastern wall originally had three apses, a large center one and a smaller one on either side, the one he found being the northern one. (Later excavations which I led outside the Old City wall would indicate that the apse Avigad uncovered was probably a smaller inner apse).

West of the wall with the apse, Avigad excavated two additional walls, one parallel to the massive wall and the other perpendicular to it—foundations of what must have been a formidable superstructure.

Further west, between the Jewish Quarter and Armenian Quarter, Avigad found the remains of structures with marble floors. These he interpreted as part of the western end of the church, possibly the courtyard or atrium.

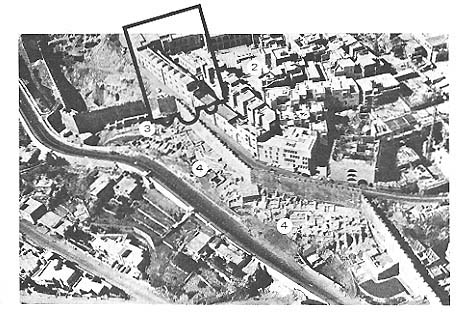

During the past two years I directed a large scale clearance outside the southern wall of the Old City, west of Dung Gate. One of the spectacular surprises of the expedition was the discovery of the south-eastern corner of a majestic edifice. Also built of massive masonry, its lines correspond to Avigad’s finds. It was obvious that we had found another segment of Justinian’s masterpiece.

The corner of the Nea we found protrudes from the base of the present south wall of the Old City which we attempted to uncover to bedrock. The southern wall and a turret extending from it cuts through the corner of the ancient Nea, thus forming the hypotenuse of a triangle of which the Nea forms the other two sides. The masonry of the Nea is clearly distinguishable from the turret and wall because the Nea masonry is so much larger and imposing. Just before the eastern wall of the Nea corner goes back under the city wall, the Nea wall forms a large apse—obviously the southernmost of the three apses in the eastern wall of the original church.

In drawing a suggested plan of the Nea, we have added supplementary details on the basis of the nearby Church of Holy Zion on Mount Zion, also built by Justinian, which the Madaba map shows to be of similar size and plan. Of basilical design, the Nea had a central nave which is flanked by an aisle on either side. The front facade had three portals, the middle one being larger than the other two.

The southern wall of the Nea served as a retaining wall for a number of public buildings, the foundations of which we uncovered. These walls no doubt supported the “two hospices” which Procopius tells us Justinian built next to the Church: “One of these [hospices],” Procopius declares, “is destined for the shelter of visiting strangers, while the 035other is an infirmary for poor persons suffering from diseases.”

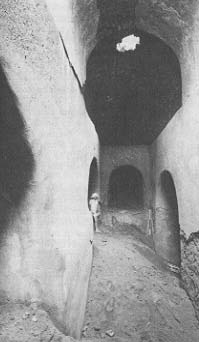

In 1976 Avigad, working inside the present Old City walls, came across a complex subterranean structure consisting of vaulted halls. This complex was first discovered by Charles Warren of the Palestine Exploration Fund in 1867–1870 and may now be identified as part of the substructure for the extensive complex of buildings associated with the Nea. In later times, however, these vaults were turned into cisterns for the storage of water. (See illustration)

One of the most astounding of Avigad’s 1976 finds was announced by the excavator at a recent lecture before the Seventh World Congress of Jewish Studies. Avigad told his audience that in the subterranean vaulting of a hospice associated with the Nea, he had found a beautifully preserved Greek inscription which mentions the name of Justinian. Although the inscription was written after the Nea had been destroyed, this monumental inscription tells us that the original building had been built in the time of Justinian, thus providing confirmatory evidence of the dating of the structure and the identification of the church as the Nea.

It is indeed unfortunate that so little remains of this magnificent church and its associated buildings. To appreciate the grandeur of the building and the technological prowess it took to build it, however, we have only to turn to the pages of that ardent chronicler Procopius:

“[Jerusalem] is for the most part set upon hills … The Emperor Justinian gave orders that [the Nea] be built on the highest of the hills, specifying what the length and breadth of the building should be, as well as the other details. However, the hill did not satisfy the requirements of the project, according to the Emperor’s specifications. For a fourth part of the church facing the south and the east was left unsupported. Consequently those in charge of this work hit upon the following plan. They threw the foundations out [and down where the hill fell off], and then erected a structure which rose as high as the rock [i.e., the top of the hill]. And when they had raised this up level with the rock they set vaults upon the supporting walls, and joined this substructure to the other foundation of the church. Thus the church is partly based upon living rock and partly carried in the air by a great extension artificially added to the hill by the Emperor’s power.

“The stones of this substructure are not of a size such as we are acquainted with, for the builders of this work, in struggling against the nature of the terrain and labouring to attain a height to match the rocky elevation, had to abandon all familiar methods and resort to practices which were strange and altogether unknown. So they cut out blocks of the region before the city, and after dressing them carefully they brought them to the site in the following manner. They built wagons to match the size of the stones, placed a single block on each of them, and had each wagon with its stone drawn by forty oxen which had been selected by the Emperor for their strength, but, since it was impossible for the roads leading to the city to accommodate these wagons, they cut into the hills for a very great distance, and made them passable for the wagons as they came along there, and 036thus they completed the length of the church in accordance with the Emperor’s wish.

“However, when they made the width [of the church] in due proportion, they found themselves quite unable to set a roof upon the building. So they searched through all the woods and forests and every place they had heard that very tall trees grew, and found a certain dense forest which produced cedars of extraordinary height, and by means of these they put the roof upon the church, making its height in due proportion to the width and length of the building.

“These things the Emperor Justinian accomplished by human strength and skill. But he was also assisted by his pious faith, which rewarded him with the honor that he received and aided him in this cherished plan. For the church required throughout columns whose appearance would not fall short of the beauty of the building and of such a size that they could resist the weight of the load which would rest upon them. But the site itself, being inland very far from the sea and walled about on all sides by the quite steep hills, as I have said, made it impossible for those who were preparing the foundations to bring the columns from outside. But when the impossibility of this task was causing the Emperor to become impatient, God revealed a natural supply of stone perfectly suited to this purpose in the nearby hills, one which had either lain there in concealment previously, or was created at that moment. Either explanation is credible to those who trace the cause of it to God; for while we, in estimating all things by the scale of Man’s power, consider many things to be wholly impossible, for God nothing in the whole world can be difficult or impossible. So the church is supported on all sides by a great number of huge columns from that place, which in color resemble flames of fire, some standing below and some above and others in the stoas which surround the whole church except on the side facing the east.”

The tremendous effort and resources spent on the project represent the apogee of the prolific Byzantine building activity—civil, religious and domestic—that graced almost every town and settlement of the Holy Land during this period. Remains dating from the fourth to the sixth century, not the least of which are churches and synagogues, are among the Land’s most impressive archaeological treasures.

Justinian was an outstanding contributor to these activities. Besides constructing the Nea and other new churches and the wilderness monastery at the foot of Mt. Sinai, he renovated and re-planned old ones, like the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, and Bethlehem’s Church of the Nativity.

The splendor of the Nea was brief. In 614, the Persian invasion left Jerusalem in ruins. The Nea suffered the fate of countless churches throughout the Holy Land and Syria. Jerusalem was reconquered by the Christians in 628, but within a decade, before repairs to the great church could get underway, the city was again captured, this time by the Moslems.

During the Omayyad period of the Moslem empire, Jerusalem became an important religious-political center, as is evidenced by the many prestigious buildings erected then, among them the Dome of the Rock, the El-Aqsa mosque and a group of palaces around the Temple Mount. To construct these new buildings, ruined churches in the area offered a source of ready-cut masonry. The Nea, conveniently close to building activity on the Temple Mount, became a veritable quarry. This explains the paucity of extant remains and the erasure, ultimately, even of memory of the site. Nowhere does it feature in the vast pilgrim literature of the Middle Ages.

Many stones have been found in Jerusalem in secondary use that still bear carved crosses and other Christian symbols, such as the symbols Alpha and Omega (the beginning and the end). Perhaps some of these stones once graced the Nea.

037Coming to light again today, the Nea’s remains are cut by the Old City’s Ottoman wall and a Crusader rampart. What was unearthed within the Jewish Quarter has been partially restored and reconstructed and will soon be open to public view. The corner of the church outside the city wall now lies at the heart of one of the archaeological gardens which form the projected green belt encircling the walls. Stretching from the Zion Gate to the Dung Gate, the Beth Shalom Garden, as it is known, was sponsored by the Christian international organization of that name, based in Zurich, which sees it as a constructive protest against the UNESCO decision on Jerusalem, taken in November 1974, condemning the archaeological excavations undertaken by Israeli archaeologists. Some ten years’ toil and research have finally been rewarded: the Nea Church—those fragments that remain—has been restored to the landscape of Jerusalem, where it will again be a lodestone for pilgrimage and scholarship.

Byzantine Jerusalem was Christian Jerusalem—par excellence. The Byzantine era began when the Emperor Constantine—soon to convert to Christianity—became master of Palestine in 324 A.D. It did not end in Jerusalem until the Patriarch Sophronius surrendered the city to the Moslem caliph Omar in the spring of 638. The Byzantine period was a prosperous one, and Jerusalem shared in this prosperity. Marked by intensive building activity, this period saw almost every inch of the city covered with construction of one kind or another. After Constantine decided to make Jerusalem the Holy City of Christendom, gifts and pilgrims followed. Gradually Jerusalem […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username