One if by Sea…Two if by Land: How Did the Philistines Get to Canaan?

How Did the Philistines Get to Canaan? One: by Sea

A Hundred Penteconters Could Have Carried 5,000 People Per Trip

Footnotes

See Bryant G. Wood, “The Philistines Enter Canaan—Were They Egyptian Lackeys or Invading Conquerors?” BAR 17:06.

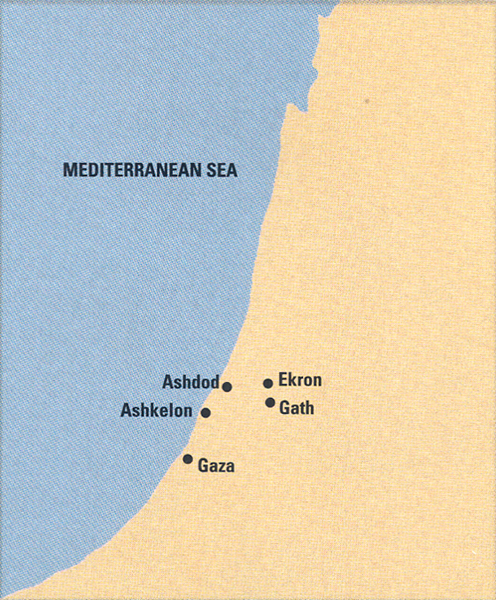

See Trude Dothan, “Ekron of the Philistines, Part I: Where They Came From, How They Settled Down and the Place They Worshiped In,” BAR 16:01; see also Lawrence E. Stager, “When Canaanites and Philistines Ruled Ashkelon,” BAR 17:02.

A megaron is a long and narrow tripartite building commonly found at Late Helladic (Late Bronze Age) sites in Greece. Often the back room contained a large circular hearth surrounded by four pillars.

For a clear explanation of the relationship of Philistine Monochrome (Mycenaean IIIC:1b) to Philistine Bichrome pottery, see Lawrence E. Stager, “When Canaanites and Philistines Ruled Ashkelon,” BAR 17:02.

See Lawrence E. Stager, “When Canaanites and Philistines Ruled Ashkelon,” BAR 17:02.

See Aren M. Maeir and Carl S. Ehrlich, “Excavating Philistine Gath: Have We Found Goliath’s Hometown?” in BAR 27:06.

Endnotes

Today, most Egyptologists prefer the Low Chronology, which yields dates of 1182–1151 B.C. for the reign of Ramesses III; see Edward F. Wente, Jr., and Charles C. van Siclen, “A Chronology of the New Kingdom,” in J. Johnson and Edward F. Wente, Jr., eds., Studies in Honor of George R. Hughs (Studies in Ancient Oriental Civilizations 39) (Chicago: Oriental Institute, University of Chicago, 1975), pp. 217–261. For the current state of Egyptian absolute chronology, see Kenneth A. Kitchen, “Regnal and Genealogical Data of Ancient Egypt (Absolute Chronology I): The Historical Chronology of Ancient Egypt, A Current Assessment,” in Manfred Bietak, ed., The Synchronisation of Civilisations in the Eastern Mediterranean in the Second Millennium B.C. (Vienna: Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, 2000), pp. 39–52.

For the full English translation of this section of the text (76.7-9), see John A. Wilson, “Egyptian Historical Texts,” in James B. Pritchard, ed., Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament (Third Edition with Supplement) (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1974), p. 262.

For a useful summary and analysis of the Biblical texts pertaining to the Philistines, see Peter Machinist, “Biblical Traditions: The Philistines and Israelite History,” in Eliezer D. Oren, ed., The Sea Peoples and Their World: A Reassessment (Philadelphia: University Museum, University of Pennsylvania, 2000), pp. 53–83.

For both types of cooking vessels at Tel Miqne-Ekron, see Ann Killebrew, “Ceramic Typology of Late Bronze II and Iron I Assemblages from Tel Miqne-Ekron: The Transition from Canaanite to Philistine Culture,” in Seymour Gitin, Amihai Mazar and Ephraim Stern, eds., Mediterranean Peoples in Transition, Thirteenth to Early Tenth Centuries B.C.E. (In Honor of Trude Dothan) (Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, 1998), pp. 379–405 (especially figs. 3.6-9, 7.19, 10.13-14 and 12.15).

Tell Qasile is a Philistine site founded ab novo roughly a generation after the initial Philistine settlement, when Philistine bichrome pottery was being produced; for the final excavation reports, see Amihai Mazar, Excavations at Tell Qasile, Parts One and Two (Jerusalem: Institute of Archaeology, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, 1980 and 1985). On the appearance of these hearths throughout the eastern Mediterranean region, particularly in Cyprus, see Vassos Karageorghis, “Hearths and Bathtubs in Cyprus: A ‘Sea Peoples’ Innovation?” in Mediterranean Peoples, pp. 276–282.

Seymour Gitin, Trude Dothan and Joseph Naveh, “A Royal Dedicatory Inscription from Ekron,” Israel Exploration Journal 47.1-2 (1997), pp. 1–16.

Christa Schäfer-Lichtenberger, “The Goddess of Ekron and the Religious-Cultural Background of the Philistines,” Israel Exploration Journal 50.1-2 (2000), pp. 82–91.

For the discovery of Late Helladic female figurines at Delphi, see L. Lerat, “Trouvailles mycéniennes à Delphes,” Bulletin de Correspondance Hellènique 59 (1935), pp. 329–375 (especially pp. 329–333 and pl. XIX); for “Ashdoda” figurines, see Trude Dothan, The Philistines and Their Material Culture (Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, 1982), pp. 234–237, fig. 9, pl. 19.

Irad Malkin, Religion and Colonization in Ancient Greece (Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1987), pp. 122–124.

For this alternative explanatory model as it pertains to the Sea Peoples in general, see Sherratt, “‘Sea Peoples’ and the Economic Structure of the Late Second Millennium in the Eastern Mediterranean,” in Mediterranean Peoples, pp. 292–313; for the application of the model specifically to the Philistine settlement, see Alexander A. Bauer, “Cities of the Sea: Maritime Trade and the Origin of Philistine Settlement in the Early Iron Age Southern Levant,” Oxford Journal of Archaeology 17.2 (1998), pp. 149–167.

A notable exception is Beth-Shean, where 23 “cylindrical and dumbbell-shaped objects” (probably loom weights) were found in Levels VIII and VII (corresponding to the 13th century B.C.); see Frances W. James and Patrick E. McGovern, The Late Bronze Egyptian Garrison at Beth Shan: A Study of Levels VII and VIII (Philadelphia: University Museum, University of Pennsylvania, 1993), p. 188, figs. 115.4-7, 118.2. Interestingly, many scholars believe that Sea Peoples mercenaries were garrisoned at Beth-Shean; for a short discussion and further references, see James and McGovern, The Late Bronze Egyptian Garrison at Beth Shan, p. 247.

For a discussion of the evidence and further references, see E.J.W. Barber, Prehistoric Textiles: The Development of Cloth in the Neolithic and Bronze Ages with Special Reference to the Aegean (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1991), pp. 283–299.

For a complete exposition of the nature of the Philistines’ migration, see Tristan J. Barako, “The Seaborne Migration of the Philistines,” Ph.D. dissertation, Harvard University, 2001.

For an English translation of the text with relevant bibliography, see Jacob Hoftijzer and Wilfred H. van Soldt, “Texts from Ugarit Pertaining to Seafaring,” in Shelley Wachsmann, Seagoing Ships and Seamanship in the Bronze Age Levant (College Station, TX: Texas A&M University Press, 1998), pp. 222–244.

See KTU 2.47, a text from Ras Shamra, in M. Dietrich, O. Loretz and J. Sanmartín, eds., Die Keilalphabetischen Texte aus Ugarit, vol. 1 (Kevelear and Neukirchen-Vluyn: Butzon and Bercker and Neukirchener, 1976).

For a drawing, transcription and German translation of the text, see Horst Klengel, “‘Hungerjahre’ in Hatti,” Altorientalische Forschungen 1 (1974), pp. 165–174.

See especially “The Date of the Settlement of the Philistines in Canaan,” Tel Aviv 22.2 (1995), pp. 213–39; also see “The Philistine Settlements: When, Where and How Many?” in The Sea Peoples and Their World: A Reassessment, pp. 159–80. David Ussishkin was the first to propose the revised “Low Chronology” based on his excavations at Lachish (“Levels VII and VI at Tel Lachish and the End of the Late Bronze Age in Canaan,” in Jonathon N. Tubb, ed., Palestine in the Bronze and Iron Ages, Papers in Honour of Olga Tufnell (London: Institute of Archaeology, 1985), pp. 213–28; however, Finkelstein has been, by far, the more vocal advocate for chronological revision.

See “Iron Age Chronology: A Reply to I. Finkelstein,” Levant 29 (1997), pp. 157–67; see also Amnon Ben-Tor and Doron Ben-Ami, “Hazor and the Archaeology of the Tenth Century B.C.E.,” Israel Exploration Journal 48.1-2 (1998), pp. 1–37.

“Chronological Separation, Geographical Segregation, or Ethnic Demarcation? Ethnography and the Iron Age Low Chronology,” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 322 (2001), pp. 1–10.

Significant also is the dearth of Egyptian XXth Dynasty finds from Philistine Pentapolis sites prior to and during the Philistine settlement. Under Ramesses III, a reinvigorated Egypt attempted to regain control of southern Canaan, an effort reflected in the numerous Egyptian finds dating to the XXth Dynasty recovered at sites in Israel, but outside of Philistia. This apparent lack of Egyptian activity during the XXth Dynasty in Philistia is no mere coincidence; the Egyptians were not in Philistia during this period because a people hostile to Egypt—namely, the Philistines—were there in their place. The weight of the evidence from Philistine Pentapolis sites is considerable, and the pattern that emerges cannot be dismissed due to the vagaries of archaeological discovery. It reflects a historical development that offers a more reasonable explanation of the archaeological data than the chronological revision suggested by Finkelstein.

See James M. Weinstein, “The Collapse of the Egyptian Empire in the Southern Levant,” in William A. Ward and Martha S. Joukowsky, eds., The Crisis Years: The Twelfth Century B.C., From Beyond the Danube to the Tigris (Dubuque, IA: Kendall/Hunt, 1992), pp. 142–150; and Manfred Bietak, “The Sea Peoples and the End of the Egyptian Administration in Canaan,” in Avraham Biran and Joseph Aviram, eds., Biblical Archaeology Today, 1990 (Proceedings of the Second International Congress on Biblical Archaeology, Jerusalem, June-July 1990) (Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, 1993), pp. 291–306.