016

017

Lying in the shadow of Mount Vesuvius, or at least in the shadow of the eruption cloud of 79 A.D., only three miles south of Pompeii, is a little-known but spectacular archaeological site: the sea-edge villas of Stabiae.

Stabiae is home to a group of enormous villae marittimae, which are set on a cliff above the modern town of Castellammare di Stabia. We know 018of at least six of these villas, built directly next to one another—a sort of Roman high-rent resort district next to the small town of Stabiae. They were beautifully preserved by the eruption of 79 A.D., with standing walls, some of the highest quality frescoes surviving from antiquity and some of the most innovative garden architecture in the Roman world.

The villas all date between April 30, 89 B.C., and the eruption of Vesuvius on August 24, 79 A.D. On April 30, 89 B.C., the legate general Lucius Cornelius Sulla destroyed Stabiae as part of the so-called Social War, in which a group of Italian principalities revolted against Rome and—paradoxically—won full citizenship after being defeated. Pliny the Elder tells us that after the town was destroyed in the war, the area was redeveloped as a zone of luxury villas.1

019

Stabiae was very different from Pompeii. If Pompeii was a bustling seaside town “on the make,” Stabiae was a place for the political elite, the pivotal upper class that was critical to the building of the Roman Empire. In the second and first centuries B.C. this elite discovered the glories (and the political uses) of the Bay of Naples. They developed a totally new setting for the rich and famous: the spectacular seaside luxury villa filled with art, sea-view dining rooms, gardens, fountains, baths, libraries and shady porticoes.

The best-preserved villas on the Bay of Naples are in Stabiae. Moreover, unlike other great and well-preserved villas along the bay, such as Oplontis, ancient Stabiae is largely unencumbered by modern buildings. It has been a protected archaeological zone since 1957, and someday soon two or three of these complexes may be excavated in their entirety, revealing gardens, stables, slave quarters and surrounding terrain, as well as luxury apartments.

Also, unlike the great villas of Oplontis or the Villa of the Mysteries at Pompeii, the Stabiae villas still preserve breathtaking views of the Bay of Naples. One can stand in a frescoed cliff-edge triclinium (three-couch dining room) and feel the cooling summer sea breezes, just as the Roman dominus (the owner, or master, of the estate) and his guests did in antiquity.

For all these reasons, Stabiae has become the subject of a hugely ambitious project, 020launched in 1998, to create an archaeological park on the site, potentially one of the largest archaeological projects in continental Europe since the Second World War (tentatively projected to cost $150 million).

The project was created by the Superintendancy of Archaeology of Pompeii, who invited the School of Architecture of the University of Maryland and the Committee of Stabiae Reborn (a local cultural/economic interest group) to join with the superintendancy to create the Restoring Ancient Stabiae Foundation (R.A.S.). The R.A.S Foundation is the first foundation in Italy created under a 1998 law to allow for the creation of semi-public and semi-private foundations that can receive and spend both public and private funds. As such it could change modern archaeology, by establishing an international foundation that shares the management of Italian cultural heritage with the Superintendancy of Archaeology.

The R.A.S. has been charged with developing the master plan for the site, involving the complete excavation of two or three of the villas, excavation of part of the supporting terrace structures on the cliff-edge (over 150 feet high!) and part of the adjacent town. It will probably also involve a museum, a promenade with sea views connecting all the villas along the entire 2.5 mile length of the site, teaching installations and summer theater.

Excavations were first opened at Stabiae 021on June 7, 1749, just one year after the excavations at Pompeii. Indeed, Pompeii was first thought to be Stabiae due to a misreading of the Tabula Peutingerina, a Late Antique road map and itinerary. Like the excavations at Pompeii and Herculaneum, the earliest excavations at Stabiae were carried out by military engineers of Charles VII Bourbon of Naples (later Charles III of Spain). A Swiss engineer, Colonel Karl Weber, working under a Spaniard named Rocco Giacchino de Alcubierre, was in direct charge. Fields were rented, and excavations were conducted either with open trenches or shallow tunnels that followed the walls. Sections of frescoes were lifted and carried to the royal palaces at Portici and Naples. When the search for frescoes in one room looked unpromising, the excavators simply punched a hole in the wall to get quickly into the next room to see what was there. Despite this piecemeal wall-chasing, the plans put together by Weber are remarkably accurate, and his notes constitute some of the first attempts to connect objects to the specific rooms in which they were found. Frescoes from this first phase of the excavation are now in the National Archaeological Museum in Naples.

Excavations ceased in 1762, began again in 1775 and then ended definitively in 1782 so that more resources could be devoted to Pompeii. The excavation trenches were simply backfilled and the fields were returned to cultivation—and the very location of the site was lost to memory.

Not until 1950 were excavations reopened, owing to the passionate determination of the principal of the local classical high school, a certain Libero D’Orsi, who began work on what is now known as the Villa Arianna using his own funds and employing a janitor and an out-of-work mechanic. D’Orsi’s intuition—that the entire edge of the hill was lined with villas—is probably correct.

Excavations gradually passed to the Superintendancy of Archaeology of Naples and later to the Pompeii superintendancy (created in 1981), but the digging was largely terminated in 1968. As a result, however, there is a substantial amount to see at the site, which is now open to the public, though only a small portion of the earlier excavations has been re-exposed.

If a major new excavation is undertaken and an archaeological park established, the Stabiae site would become part of a circuit of archaeological sites—including Pompeii, Herculaneum and the museum and villa rustica at Boscoreale—providing 022an unusually complete panorama of Roman culture during the first centuries B.C. and A.D. (a pivotal period during which Rome changed from a republic into an empire). Pompeii and Herculaneum exemplify the urban environment of small bustling port towns; the villa at Boscoreale represents a kind of agricultural plantation that supported the famous cuisine of the area; and Stabiae offers the villas that were the seat of the social class that really wielded power.

In the last century of the Roman Republic (the first century B.C.), the Bay of Naples presented one of the most spectacular sights on the inhabited earth. It had become so much the favorite place for the powerful and wealthy of Rome that the Greek geographer Strabo, writing at the end of the first century B.C., could describe the shores between the capes of Misenum (to the north) and Surrentum (to the south) as being “entirely laid out with towns and villas and gardens in an unbroken line, giving the appearance of a single city.”2

The villas on the cliff at Stabiae were just the southern end of this vast luxury community of Rome’s powerful elite. Sulla, Lucullus, Crassus, Pompey, Caesar, Cicero, Augustus, Tiberius and the family of Nero’s third wife were among those who had villas on the bay. In these villas, several of the most important events of the end of the republic and early empire occurred. At his villa at Misenum, Lucius Cornelius Sulla (138–78 B.C.), after stepping down from the dictatorship, spent his final months in a wild sybaritic life of sensual indulgence that broke his health. Also at Misenum, the 18-year-old Pliny the Younger watched the volcanic eruption of 79 A.D., while his uncle, Pliny the Elder, a famous historian and administrator of the fleet at Misenum, sailed off to Pompeii in an attempt to record the event and rescue victims—and then died on the beach at Stabiae during the eruption. In 14 B.C. Augustus bought the entire island of Capri and apparently built 12 villas there. Tiberius (14–37 A.D.) retired to one of Augustus’s Capri villas, the Villa Iovis, which he heavily rebuilt; Tiberius then ruled the Roman Empire from Capri during the last 12 years of his life. Nero (54–68 A.D.) finally succeeded in murdering his mother, Agrippina, in the bay at Baiae. (A self-scuttling boat failed to drown her, so he took a more direct approach and had her clubbed to death on the shore.)

None of the owners of the known villas of Stabiae, however, has been identified to date. Whether senators, equestrians or merchants, they were enormously wealthy.

The type of villa represented at Stabiae—a huge seaside luxury villa with peristyle (colonnaded) courtyards, nymphaeum-fountains, private baths and dining rooms with sea views, often supported on multiple terraces going down to the sea—was an original architectural creation of the first century B.C. In this period there was explosive political competition among the Roman elite, with huge fortunes to be made at the top of the social heap. The vast luxury villa was one of the creations of that elite.

This “power elite” was not just a highly privileged class (some 300 to 600 men and their families of the senatorial order and perhaps 10,000 of the so-called “equestrian,” or business, order) but an upper class that was remarkably skilled. To rise in that competitive elite, an individual had to master public speaking, administration, finances, military tactics, intellectual culture and religious ritual.

Competition within this elite may explain the amazing capacity for progressive innovation that Roman culture demonstrates through several centuries. Politicians were always on the lookout for new ideas and talents, whether for public spectacles (gladiatorial games) or public works (aqueducts, roads, temples). Hence the constant creative borrowing and synthesizing, as well as the constant searching for talent, purchased or hired, local or foreign. Wealthy Roman aristocrats of this period knew how to pick (or buy) architects, administrators, painters, cooks, poets and philosophers.

In the second or early first century 023B.C., it dawned on them (or at least some of them) that a lifestyle could be fabricated from the combination of city comforts, country beauty and art (previously used exclusively in the service of religion) with luxury, to create a life that could enhance their social position. A lifestyle of art, luxury and erudition would surround them with the aura of being superior creatures who lived in an Aurea Aetas, a golden age. The political and social uses of the villas were not simple ostentation. Their main use was to allow the host to control social interaction in an environment that suggested his or her social superiority.

The domus (townhouse) and villa (country house) were so important to the elite because they were both visible and immediately available to a large public. In Rome the men (and probably often their wives) did as much business in the atrium (main front room) of their domus as they did in the Forum or Curia (Senate House). In the early hours of the day their atria and the streets outside were filled with a milling crowd of “clients,” that is, a network of political friends and dependents. This was the ritual of the salutatio, the morning greeting, which began the day. When the dominus of the house stepped out in the morning for a court or Senate session, his throng of clients would follow the great man to the Forum, leaving the domina to run the house. Tiberius Sempronius Gracchus, the radical reformer of 133 B.C., supposedly was followed by a crowd of some three thousand “clients” when he strolled from his house near the Forum to the Senate. In the late afternoon or evening a select few (or sometimes a select many) would be brought home to dine, and would be conducted by slaves to the more privileged dining rooms inside the house.

As both the potential fortunes and 026potential risks became greater, the luxurious country villa also became seen as a political asset (as well as, presumably, a reward). In time the elite families would have not just one villa but a string of villas so they could “be at home” in dignified fashion (that is, control the environment of their visiting provincial clients) even when they traveled to different locations, or so they could offer hospitality to their friends when they traveled. Caesar had a number of country villas. Cicero supposedly had eight, including three on the Bay of Naples (one at Cumae, one at Puteoli and one near Pompeii, which was his favorite because no one bothered him there).

Many of the new features of first-century B.C. high-status houses (both atrium-and-peristyle townhouses and villas) were borrowed from Hellenistic public architecture, rather than from private architecture. The great peristyle courts of the villas were meant to look like a Greek agora, or even sanctuaries scattered with statues. As the late-first-century B.C. Roman architect Vitruvius directed:

For the most prominent citizens, those who should carry out their duties to the citizenry by holding honorific titles and magistracies, vestibules should be constructed that are lofty and lordly, the atria and peristyles at their most spacious, lush gardens and broad walkways refined as properly befits their dignity. In addition to these, there should be libraries, picture galleries, and basilicas, outfitted in a manner not dissimilar to the magnificence of public works, for in the homes of these people, often enough, both public deliberations and private judgments and arbitrations are carried out.”3

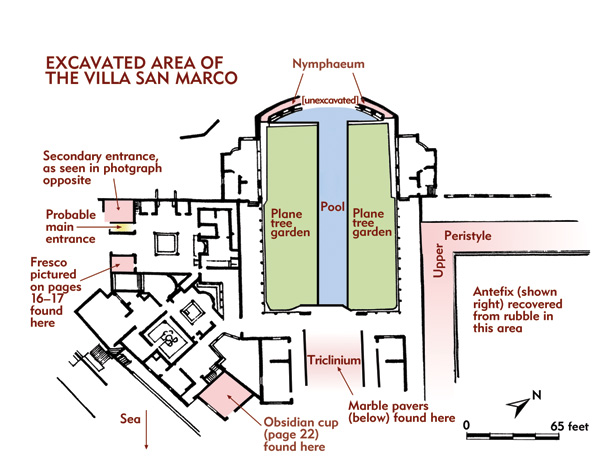

One of the most elaborate villas in Stabiae is the Villa San Marco (named after a relatively modern neighboring chapel dedicated to St. Mark). This partially excavated site includes 65 rooms, corridors, entrances, courtyards, pools and indoor gardens. As a whole, it almost seems more of an entertainment complex than a residence. Five small cubicula (multi-functional private rooms for the main members of the family) surround the atrium but the rest of the complex includes dining rooms, “day rooms,” two vast porticoes for strolling after dinner (to aid digestion, Pliny tells us) and a full private bath complex. (No library and no latrine have been found). A large summer triclinium opens onto a terrace facing Mount Vesuvius and the sea. A gentle breeze would waft through the room even in the heat of summer. In the standard triclinium, nine guests were accommodated on three couches in a U-shaped configuration. Diners would recline, propping themselves up on their left elbows. Food and 027drink were placed on small tables in front of the couches.

The floor of the San Marco triclinium is paved with marble in the opus sectile style (in which precisely cut pieces of stone, or tesserae, are fit together to form a mosaic) and its frescoed walls gleam in red and blue hues, reflecting a uniquely Roman joie de vivre. Corridors from the triclinium lead to more private resting rooms. The passageway through the villa winds around a totally internal viridarium, or miniature garden.

The lower peristyle features what may be a fishpond and one of the most complex multi-media nymphaea outside Rome. (A nymphaeum is a kind of grotto/fountain, supposedly dedicated to the nymphs.) The shallow apse with engaged columns frames panels of relief stuccoes (in the so-called Fourth Style from Pompeii; see the box), a vitreous mosaic, water jets and a marble urn. A crypto-porticus, or underground porch, provided a shaded place to escape the summer heat.

The enormous upper peristyle at San Marco featured some of the earliest spirally fluted columns in Italy (stucco over brick) and an amazing series of ceiling frescoes that seem to suggest the cosmic cycle of the seasons. Unfortunately, the colonnade of the peristyle collapsed in an earthquake in 1980, but a geophysical survey undertaken in 2002 demonstrated that the peristyle probably continues to a length of over 300 feet, most of it still unexcavated.4

The Villa Arianna on the Varano hill, a short walk from the Villa San Marco, also boasts a splendid panoramic view. Compared to the Villa San Marco, the Villa Arianna is a much more sprawling complex built in several phases. The core of the villa is a conventional “Vitruvian” villa, with an entrance peristyle preceding the main atrium (reversing the usual layout of spaces in which the large front room, or atrium, opened onto an open, interior colonnaded court, or peristyle).

050

As a result of having been built in stages, the Villa Arianna features some early Second Style frescoes as well as some Third Style and Fourth Style frescoes (see box). In the end, the complex included private apartments, another enormous (though still unexcavated) peristyle and a working farm.

These structures rested on one of the most spectacular features of this villa, a series of terraces (perhaps as many as six) rising nearly 150 feet from the base. The terraces rest on vault buttress chambers; a private ramp passes under the villa and zigzags down to the beach.

The most famous frescoes from Stabiae are also found at the Villa Arianna. Images of Leda, Flora, Diana and Medea decorate the walls of a two-room apartment facing the entrance peristyle. Each of these figures is isolated (in the middle of a Fourth Style central panel), drifting as it were in a void with almost no ground line. The choice of female images from mythology suggests that this was a woman’s apartment, probably for the domina or her daughter: Leda mating with Zeus, who has taken the form of a swan; Flora, the goddess of all that flowers; Diana, protector of childbirth; Medea, who takes revenge for Jason’s infidelity by murdering their children.

The most politically and socially important rooms seem to have been the dining rooms (triclinia). Multiple triclinia gave the host the chance to choose the one that was best for the season—perhaps a lightly colored north-facing room for summer, and a darker south-facing room for winter—or even for the time of day. Pliny the Younger mentions that one host had different budgets for different dining rooms, thus introducing a new subtlety into the perquisites of social status and a new way to insult less-prominent guests in a highly status-conscious society.

Dinner guests could be invited days in advance, or they could be “picked up” during the day. In the late afternoon, around the “eleventh hour” of the Roman sundial (our five o’clock), the wealthy Roman dominus would often return from town or forum, having finished the day with a session at the public baths. Better yet, if he were wealthy enough to have his own private bath complex, he would invite some of his closer associates or clients to use this private facility. An invitation to stay for dinner might follow the bath. Lower-status dependents, like the first-century A.D. poet Martial, would often spend a good part of their day hoping to run into some patronus who might invite him to a free meal.

The women of the house normally dined with the dominus and his male guests. From the mid-first century B.C., the more “progressive” women dined lying on the couches with the men, as opposed to the older custom of having the women seated on chairs in front of the couches. Roman women moved about freely in all parts of the house—a very different custom from that of the Greeks, who kept women out of view of the guests. Certain high-status Roman women must have exercised a good deal of political and social power, since so much political and business activity did occur in the house, where they were free to move around. Hence women were able to be intimately informed of events and to establish contact with political men. It has been estimated that as much as 7 percent of the election graffiti painted on the walls of Pompeii between 62 and 79 A.D. were signed by women, even though women did not vote.

In the course of the first century A.D. the idea of the “good life” lived in the Stabiae villas trickled down to other levels of society. In the decades before the eruption of Mount Vesuvius, tiny imitations of the villa sprung up just behind the great seaside villas of Stabiae. One of these tiny imitations, the villa rustica at Carmiano, even featured a full triclinium decorated with Dionysiac scenes of wine-drinking, singing and cavorting. Dionysiac scenes are by far the most popular subject matter in first-century A.D. frescoes in the area around Vesuvius; the subject matter carried connotations of the “good life” represented by the 051god of wine, and of the immortality achieved by the once-mortal Dionysus.

The original impetus to create the villa lifestyle was the desire on the part of the elite for an ambience which emphasized their social superiority. Once this image of an idealized lifestyle was shaped, it could be borrowed. The rich set the fashion for the not-quite-so-rich. The image of an idealized Dionysiac lifestyle in an Elysian world of divine art, ambrosial cuisine, shady gardens and beautiful sea-views was highly appealing to everyone. It still is.

All uncredited photos courtesy of the Superintendency of Archaeology of Pompeii.

Lying in the shadow of Mount Vesuvius, or at least in the shadow of the eruption cloud of 79 A.D., only three miles south of Pompeii, is a little-known but spectacular archaeological site: the sea-edge villas of Stabiae. Stabiae is home to a group of enormous villae marittimae, which are set on a cliff above the modern town of Castellammare di Stabia. We know 018of at least six of these villas, built directly next to one another—a sort of Roman high-rent resort district next to the small town of Stabiae. They were beautifully preserved by the eruption of […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Endnotes

Marcus Vitruvius Pollio, Ten Books on Architecture, trans. Ingrid Rowland and Thomas Noble Howe (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1999), 6.5.5.