“In the thirty-first year of Asa king of Judah, Omri became king of Israel and reigned for twelve years. He reigned for six years at Tirzah. Then for two talents of silver he bought the hill of Samaria from Shemer and on it built a town which he named Samaria after Shemer who had owned the hill.”

(1 Kings 16:23–24, NEW JERUSALEM BIBLE)

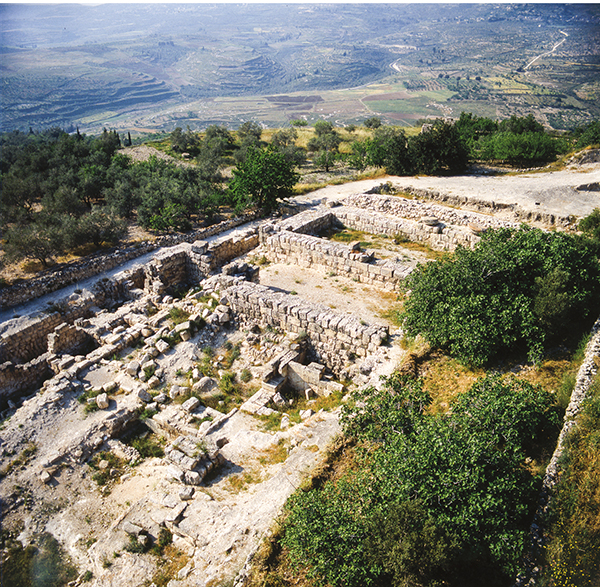

By the detailed, and very complicated, study of the dates given for the various kings of Israel and by the cross-linking of those dates with the independent dating of the kings of Assyria (who, in some of their inscriptions, mention some of the kings of Israel), it is possible to establish that the date of the foundation of the royal complex at Samaria occurred in about 880 B.C.E. King Omri of Israel and his successors reigned from Samaria until the fall of the kingdom of Israel in 721 B.C.E. After that it became, in succession, the residence of the governor of the Assyrian, Neo-Babylonian, Persian and Hellenistic province of Samaria. During this long post-Israelite period, it is clear from the archaeology that the former Israelite royal complex underwent a great deal of neglect (there are pits from this span of periods across the excavated area), but very little modification.

Students of the site are fortunate for several reasons. It is one of the best preserved royal complexes in the southern Levant. The site had no prior urban occupation, so it gives a good chronological “fixed point” for the whole Iron Age sequence in the region. Finally, it was excavated by two of the greatest stratigraphic excavators and analysts in the history of archaeology: George Reisner of Harvard University and British scholar Dame Kathleen Kenyon.

That’s the good part. Strangely, the excavations by those giants were given little more than passing mention in later scholarly syntheses and detailed studies. No doubt, part of the reason for the lack of attention to Samaria is the fact that the Harvard team worked at the site in 1908–1910, a time when very little was known of either the pottery taxonomy of the Iron Age or its architecture. As for Kenyon’s excavations in the 1930s, for reasons that remain unclear, the archaeologists published what is, in effect, a summary of their conclusions, without the detailed evidence and analysis on which those conclusions were based. This has meant that, using their report, one could only address the questions they asked to a limited extent. Later scholars could only quote their conclusions, but not the evidence on which those conclusions were based. Questions they did not ask could not be addressed at all.

Toward the end of the 20th century, Harvard’s Lawrence Stager got into it. He tried to understand two walls better, so he and his colleagues went back to Kenyon’s field books, but there were no more details there than in the published accounts.1

Ron Tappy, Stager’s student, later at the University of Pittsburgh, picked up the cudgels, inaugurating a new stage in the understanding of Reisner’s and Kenyon’s excavations. Tappy ultimately published two substantial volumes.2 It is this publication that has made my own work possible.

For a number of years, I have been working on a reanalysis of the excavated evidence at Samaria, hopefully raising some more significant questions than could have been raised prior to Tappy’s excellent work.

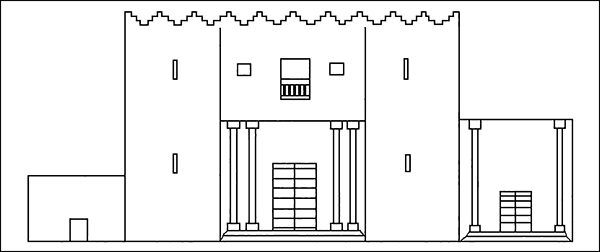

In my view, the palace that Omri built at Samaria was a bit hilani. The word bit means “house,” and the word hilani means “window” (in Hebrew). Thus a bit hilani must feature one or more windows. This has usually been thought to refer to clerestory windows, that is to say, windows in the upper walls of a room (as opposed to windows at the floor level of the room). However, I have a different suggestion, based on archaeological evidence, to which I will return. What is crystal clear is that the bit hilani was a royal reception suite, a formal setting in which a king could receive visitors and also show himself to the assembled adoring multitudes. In plan, it is now clear that a bit hilani consisted of a building that sat on a raised podium, which was approached by a wide flight of steps, a pillared portico and sometimes flanked by a guardroom. At the back of the portico was a monumental doorway, opening into an anteroom, which, in turn, led by another monumental doorway into a transverse room, broad and high, with the dais and throne at one end.

One possible interpretation of the name bit hilani would be to see it as a reference to this throne room, interpreting the room as reaching to the full height of the building, being lit by clerestory windows. There is no such structure that has survived, and this interpretation could be corroborated only by the discovery of a depiction of a palace with clerestory windows labeled as a bit hilani.

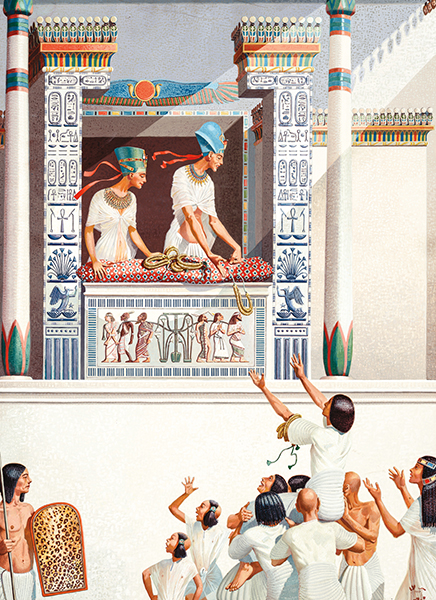

An alternative suggestion arises from Sir Leonard Woolley’s reconstruction of the palace at Alalakh in Syria, which clearly exhibits one of the earliest examples of the bit hilani plan. He also found, in the collapsed remains of the portico, evidence suggesting to him that above the portico there was a large opening, a window of the sort called a “Window of Appearances” in the inscriptions from the palace of Akhenaten at Tell el-Amarna in Egypt.3 Here the king was accustomed to show himself to the assembled people.

It’s also worth noting that Woolley’s own reconstruction of this window was that the antae of the portico only came up to the level of the roof of the portico and supported a balcony across the width of the window, comparable to that on the front of Buckingham Palace. Given that the grammatical form of the name for the architectural form is in the singular, rather than the plural, it may be that the window in question is a Window of Appearances above the entrance of the palace. We also have a famous illustration of such a window in the form of the “Woman at the Window” Phoenician ivory carvings, as well as the remains of one such window excavated in the palace of the Judahite kings at Ramat Rahel. This argument is, I think, reinforced by the account of the death of Queen Jezebel of Israel, who was thrown out the “window” (2 Kings 9:30–37).

The point of all of this perhaps tedious definition is that if one looks at the plan of the palace of Omri at Samaria, the plan of a bit hilani palace emerges as the clearest—perhaps the only—yet found in the southern Levant. On the north side of the palace was a large rectilinear building with no internal partitions that I have tentatively identified as a temple, which, again, has parallels with various north Syrian sites, most notably Tell Tayinat.a

In his study of the field records of Kathleen Kenyon’s excavations at Samaria, Ron Tappy made two startling and remarkable discoveries. The first of these was that there is no archaeological evidence for an Assyrian destruction here in 721 B.C.E., as is traditionally assumed based on the Biblical text: “The king of Assyria invaded the whole country and, coming to Samaria, laid siege to it for three years. In the ninth year of Hoshea, the king of Assyria captured Samaria and deported the Israelites to Assyria. He settled them in Halah on the Habor, a river of Gozan, and in the cities of the Medes” (2 Kings 17:5–6, New Jerusalem Bible).

This fact is significant for the site as a whole, in that it means that it is actually quite difficult to discern the point at which the kingdom of Israel comes to an end. While Samaria provides a fixed point for the dating of the reign of Omri in the early ninth century B.C.E., it provides no such fixed point for the end of the kingdom of Israel. There is no archaeological evidence that the palace of Omri was destroyed by the Assyrians.

When the Assyrians took Samaria in 721 without destroying it and decided to create the province of Samaria, they required a suitable residence for their provincial governor. In the palace of Omri and his successors, they found a building of a type with which they were completely familiar—it was even decorated with the same style of Phoenician carved ivory and bone inlay in the furniture and cedar paneling with which they were familiar (as we know from the rich ivory carvings discovered at Nimrud and on a smaller scale at Samaria itself). And what better way to emphasize their legitimacy and dominance than by making their headquarters in the former palace of the deposed kings of Israel?

The transitions from Assyrian to Babylonian rule, from Babylonian to Persian rule and from Persian to Hellenistic rule were, on the whole, relatively peaceful in the southern Levant. Although there was a major Samaritan revolt against Alexander the Great, which was put down with the utmost brutality, there is no indication of a destruction at Samaria itself. The excavations revealed that there was no wholesale remodeling of the buildings of the old royal compound until the Late Hellenistic period when solid round towers were added to the great retaining wall at certain points as platforms for the newly developed ballistas and some new ancillary buildings were constructed.4 Otherwise, the site continued to be used in much the same fashion as it had been since the time of Omri.

Then, late in the Hellenistic period, there came a great change. The Hellenistic world was dominated by three great kingdoms: Macedonia, the Seleucid empire and Ptolemaic Egypt. The latter two were conquest kingdoms with ruling Macedonian families for whom their kingdom was their personal property—to be exploited as they saw fit. This resulted in governments that were corrupt and venal to the nth degree, purely exploitative with a massive inequality of wealth, with governing dynasties in which members of the extended families were pitted against one another in a lethal competition for control of power and wealth, backed by massive mercenary armies. These three kingdoms battled for control of the Mediterranean world. One incident involved a clash between the Seleucid king Antiochus IV Epiphanes, who ruled over the region of Syria and Palestine, and Ptolemaic Egypt and Rome. Antiochus ultimately withdrew to Syria—raiding the Temple in Jerusalem and looting its treasury on the way. This, of course, triggered the Maccabean Revolt, which ushered in a century of independent Jewish rule in Judea.

This brings me to the second of Ron Tappy’s remarkable discoveries in his reassessment of Kenyon’s excavations at Samaria—the findspot of the Samaria ivories. Over a period of a few days, between May 28 and June 2, 1932, Kenyon’s team uncovered a remarkable collection of Phoenician-carved ivories dating to the Iron Age, the largest such assemblage ever found in the Levant.b These ivory carvings were immediately and rightly connected with the famous statement that Ahab had built for himself an “ivory house” (1 Kings 22:39).5

Because many, although not all, of the Samarian ivories were burnt, and because a large part of the ivories were fragmentary, it was assumed by the excavators (and by everyone since), that their condition and deposition were a result of the equally assumed Assyrian destruction; however, as we have already seen, there was no Assyrian destruction. The startling discovery that emerged from Tappy’s analysis of the stratigraphic data concerning their findspot was that they came not from Iron Age deposits, but from Late Hellenistic ones.6 These ivories had been intentionally deposited together in an area that was, curiously, nowhere near the palace. It seems that at some point between the Assyrian conquest in 721 B.C.E. and the Late Hellenistic period, the ivories had been moved from the palace to a storeroom in an ancillary building, presumably either because they had begun to deteriorate from age or simply because they were no longer fashionable. There they remained until the site was remodeled in the Late Hellenistic period. When Antiochus IV Epiphanes constructed the fortress and burnt the ancient furniture, he desposited the remains in a hole—where archaeologists later discovered them.

Samaria is an extremely important site, which has been badly neglected over the past century since it was first excavated. I hope that this brief examination of the evidence from the Iron Age onward has shown just how much the site has to offer to our understanding of the southern Levant and, indeed, the Hellenistic world.

MLA Citation

Footnotes

See Victor Hurowitz, “Solomon’s Temple in Context,” BAR, 37:2.

See “The Samaria Ivories—Phoenician or Israelite,” BAR, 43:05.

Endnotes

Lawrence E. Stager, “Shemer’s Estate,” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 227/228 (1990), p. 99.

Ron E. Tappy, The Archaeology of Israelite Samaria, Volume I, Early Iron Age Through the Ninth Century B.C.E., Harvard Semitic Studies 44 (Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1992); Ron E. Tappy, The Archaeology of Israelite Samaria, Volume II, The Eighth Century B.C.E., Harvard Semitic Studies 50 (Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 2001).

Sir C. Leonard Woolley, Alalakh: An Account of the Excavations at Tell Atchana in the Hatay, 1937–1949, Reports of the Research Committee of the Society of Antiquaries of London 18 (London: The Society of Antiquaries, 1955), pp. 116–117.

Anthony W. McNicoll, Hellenistic Fortifications from the Aegean to the Euphrates (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1997).

A detailed preliminary report of them was published: John W. Crowfoot and Grace M. Crowfoot, “The Ivories from Samaria,” Palestine Exploration Fund Quarterly Statement 64 (1933), pp. 7–26, Plates I–III. This was followed by a somewhat less detailed “final report” volume: John W. Crowfoot and Grace M. Crowfoot, Early Ivories from Samaria, Samaria-Sebaste: Reports of the Work of the Joint Expedition in 1931–1933 and of the British Expedition in 1935, vol. 2 (London: Palestine Exploration Fund, 1938).