Temple Mount Excavations Unearth the Monastery of the Virgins

020

020

For ten years, between 1968 and 1978, the area south of the Temple Mount in Jerusalem was intensively excavated by archaeologist Benjamin Mazar.1 His many spectacular discoveries included the remains of a monumental staircase that led up to the southern enclosure wall of the massive platform built by Herod to support the gleaming Temple that he had luxuriously rebuilt. Mazar also found a previously unknown caliph’s palace complex from the early Arab period (late 023seventh to early eighth century C.E.), a glorious era in Islamic history that also saw the construction of the golden Dome of the Rock and the al-Aqsa Mosque atop Herod’s Temple Mount.

Unfortunately, Professor Mazar died in 1995 without completing the final report of the excavation, although he left a vast amount of field materials—notes, drawings, plans and, of course, artifacts. In 1996 the board of the Institute of Archaeology of the Hebrew University authorized me to publish the finds from the excavations since I had been Mazar’s research assistant, as well as an area supervisor in the City of David excavations directed by Yigal Shiloh (1981–1985). In addition, I had directed my own excavations at the Ophel (1986–1987), the area just below the Temple Mount. I enthusiastically accepted the assignment with special love and devotion. Benjamin Mazar was my grandfather.

One of the volumes resulting from the work has already appeared, others have been written and await publication, and we are still working on others.2 Here I would like to report on an unusual discovery—a Christian monastery from the Byzantine period (fourth century C.E. to 614 C.E.) that is described in detail in our recently published final report.3

Some readers may be surprised to find a Christian monastery at the base of the Temple Mount. A Jewish or Muslim presence at the site is certainly understandable. For Jews, this is the site of Solomon’s Temple. After the Babylonians destroyed this first Temple in 586 B.C.E., a Second Temple, more modest than the first, was built by the returning exiles (later in the sixth century B.C.E.). Then, just before the turn of the era, Herod the Great rebuilt this structure. Herod’s Temple Mount compound itself, one of the surviving marvels of the ancient world, was as large as 24 football fields. Of Herod’s gold-and-marble Temple, the first-century C.E. Jewish historian Josephus wrote, “To approaching strangers [the Temple] appeared from a distance like a snow-clad mountain; for all that was not overlaid with gold was of purest white.”4

The Romans destroyed the Herodian Temple in 70 C.E. Much later, in the seventh century, the Muslims conquered the city and adorned what had been the Jewish Temple Mount with the gleaming Dome of the Rock. So it is natural that structures from this Muslim period 025also exist south of the enclosure wall. Here stood an early Arab palace complex from which there was a bridge directly onto the ancient Jewish enclosure.

How can we account for Christian structures, however, south of this great wall?

In 130 C.E., 60 years after the Romans destroyed Herod’s Temple, the Roman emperor Hadrian (117–138 C.E.) founded a Roman pagan city on the ruins of Jerusalem; he named it Aelia Capitolina. On the old Temple Mount he built a temple to Jupiter. The finds from the excavations indicate that the camp of the Tenth Legion may have occupied the area at the foot of the southwestern corner of the Temple Mount enclosure as well as the Temple Mount itself.

026

In the fourth century, however, the city became Christian. This area south of the Temple Mount enclosure became a Byzantine neighborhood with no special relationship to the Temple Mount. Churches, a monastery, a hospice, shops, workshops and private houses were built haphazardly. Then, during the fifth and, even more so, in the sixth century, as the area became more crowded, its character changed. More public facilities were built for the many pilgrims visiting the city.

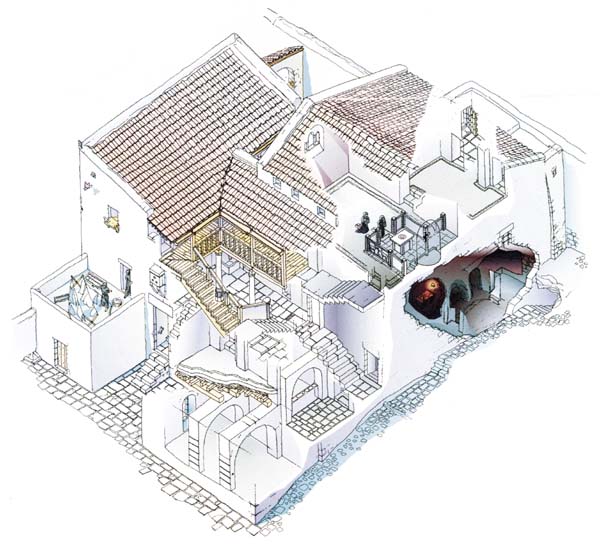

I will here examine the monastery, which consists of three parts: the monastery itself, an adjacent winery and a separate hospice for pilgrims. As we will see, the monastery also yielded information about what had come earlier, during the Herodian period.

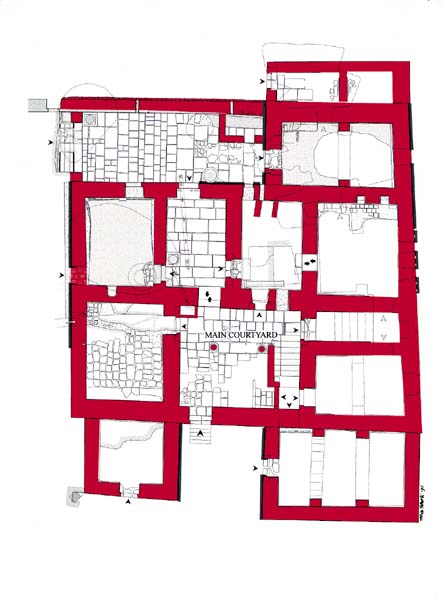

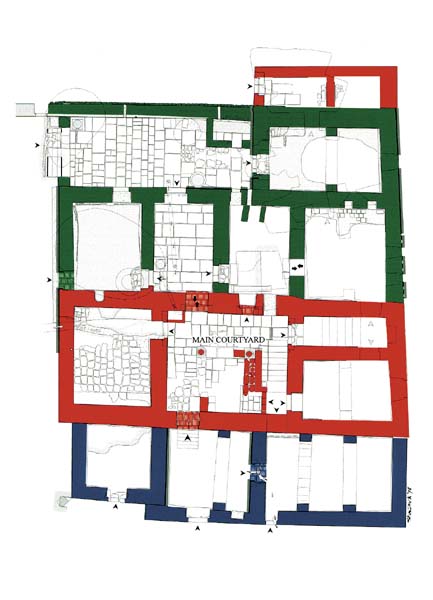

The monastery building is a large—but typical—Byzantine courtyard structure (see plan opposite, top). It is almost square (about 60 feet on a side), with a central courtyard around which a dozen or so rooms are arranged. Of its original three stories, the basement and ground floor are in an excellent state of preservation. Here and there we can still see second-story walls. A set of stairs leading to the second story looks almost new. Some of the walls still stand to a height of 8 feet and more. Most of the floors are paved with stone slabs, but two rooms are paved with plain white mosaics. The plaster on the walls was also preserved in places, often with a bluish cast; originally, all the walls were plastered.

027

But there was something strange about some of the exposed masonry walls. Most of them are built of fairly coarse stones, with many small fieldstones in between—typical of Byzantine construction. But in places, particularly in the eastern wall and in the courtyard of the northwest corner of the monastery, the walls are built of large, finely dressed, smooth stones very carefully fit into place and plastered and molded at the joints between the stones—typical of Herodian construction. Apparently, part of an earlier Herodian structure was incorporated into this later Byzantine structure. Not only did my grandfather note this in his field book, but in 1998, when the area was prepared as an archaeological park, a thin Byzantine wall was removed from outside the monastery’s western wall, exposing more of the Herodian masonry in the wall of the Byzantine building! The wall contained a sealed entrance to the Herodian building. The removal of the sealing stones revealed Herodian paving stones on the threshold of the entrance.

Here then were the remains of a large Herodian building adjacent to the southern wall of the Temple Mount (at the foot of and east of a major entrance, the Triple Gate), at the most prominent point in the city, where masses of Jewish pilgrims once gathered to enter the Temple compound. My grandfather suggested that this Herodian structure might be the courthouse referred to in the Mishnah (the earliest collection of rabbinic law, codified in about 200 C.E.) as being located “at the entrance to the Temple Mount.”5

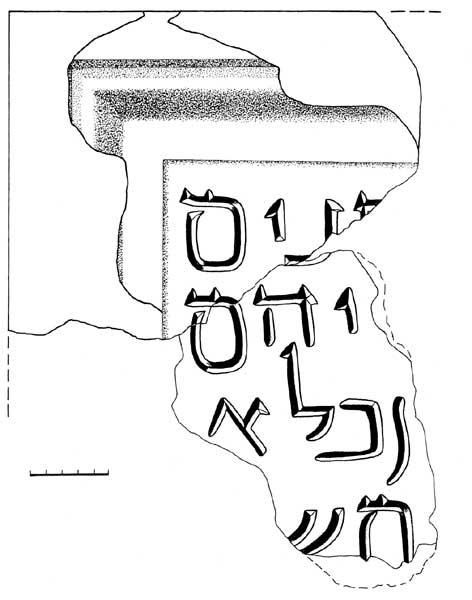

This suggestion is supported by a fragment of a Hebrew inscription found near the Triple Gate, very close to the monastery, containing the word “elders” ([… z]kenim), probably referring to the elders of the Sanhedrin, the supreme Jewish legislative and judicial body. Another fragment of this inscription was found in the 19th century and can now be joined to our fragment, but we have thus far been unable to decipher it. This fragment may well have been a dedicatory inscription attached to the wall of the courthouse.

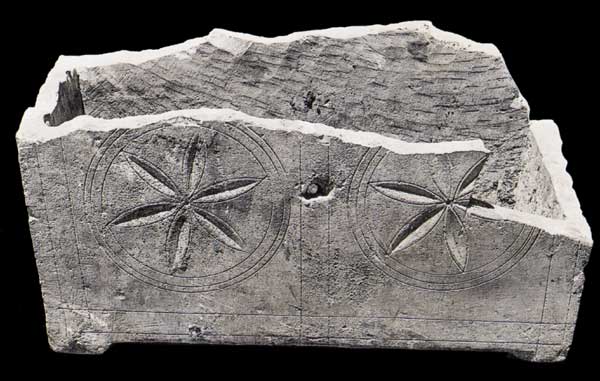

The great bulk of the finds in the Byzantine structure, however, were Christian. Notably, crosses were ubiquitous. A stone lintel, for example, has a cross enclosed in a wreath painted on it. A marble column capital was carved with a cross. A so-called basket capital was also embellished with a cross. Clay oil lamps were decorated with crosses. A red bowl featured a cross. Two roof tiles were stamped with a Byzantine cross (arms of equal length). A copper alloy pendant was similarly decorated with an equal-armed cross. The back of a metal door knocker is in the shape of a cross (see cover).

028

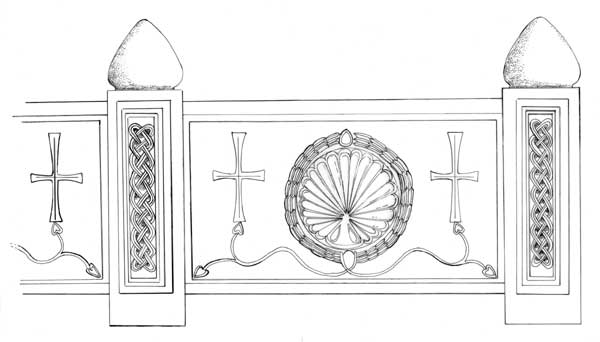

Equally impressive are large copper-alloy crosses that may have hung in the apses of the monastery’s chapel on the second floor; these crosses have a vertical post longer than the horizontal arms—a common Byzantine feature. A number of other objects from the chapel were also uncovered, including fragments of an altar table. The many fragments of chancel screens and posts that emerged in the excavation are the clearest indication that the building was a monastery, however. Chancel screens, mostly of marble, divided the nave of a chapel or church from the apse containing the altar. Many are quite beautiful. Several chains for suspending incense bowls were also found. We even found a complete incense bowl with its chain attached, together with a hook for hanging it.

We assume the chapel was on the destroyed second story of the monastery, above the ground floor rooms where fragments of chancel screens and posts were found; the second-story rooms themselves did not survive.

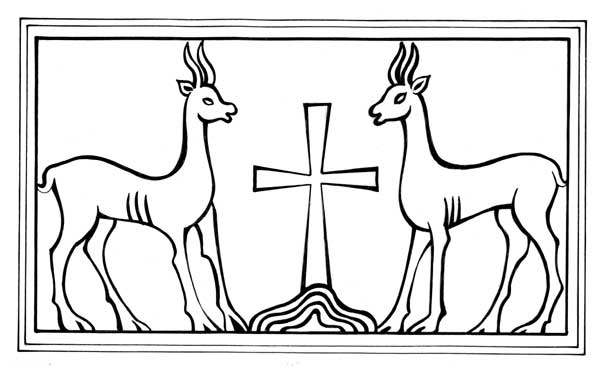

Five surviving fragments show that a marble chancel screen was originally decorated with two facing harts and a cross. The hart was a common Christian symbol at the time. It recalls Psalms 42:2: “As the hart panteth after the water brooks, so panteth my soul after Thee, O God.” Therefore, the hart is a symbol of devotion and strong religious belief. Also, because the hart tends to seek shelter in high terrain, early Christians viewed the hart as a symbol of solitude and pure living.

The cross on the chancel screen stands on the Hill of Golgotha, depicted here as the “Tree of Life,” from which is flowing the four sacred rivers of the Garden of Eden: the Pishon, the Gihon, the Tigris and the Euphrates. According to Christian tradition, the four rivers flowing from the rock are analogous to the four Gospels emanating from Christ. The rivers—or the Gospels—quench the spiritual thirst of mankind, in the same way that the water released from the rock struck by Moses quenched the thirst of the people of Israel in the desert (Numbers 20:11).6 The cross on Golgotha alludes, therefore, not only to the crucifixion, but also to the redemption of which humanity was deemed worthy in the aftermath of the crucifixion.

The marble panels of chancel screens were fit into slots in marble posts, fragments of which were also found in the excavations. We even found a few fragments from corner posts that have slots on two sides.

The excavation of the monastery also produced fragments of ossuaries—limestone bone boxes used by Jews in the Herodian period. But in the monastery, they were in secondary use—as reliquaries (a depository for 029sacred objects)—another indication that the structure was a monastery. Although we have no other excavated examples of the phenomenon, ossuaries from the earlier period could easily have been invested with religious meaning for Byzantine Christians, as my colleague Leah Di Segni has observed, in the belief that the ossuaries contained the remains of someone mentioned in the Gospels or of an early Christian martyr from one of the persecutions ordered by the Roman emperors. Fragments of Jewish ossuaries have been found in several Christian sacred places, so perhaps in the future we will find examples where they have been used as reliquaries.7

The monastery building seems to have been built in two phases, the first from the second half of the fourth century C.E. to the mid-sixth century C.E., the second from the mid-sixth century C.E. to 614 C.E., the date of the Persian conquest of Jerusalem. In the early phase, the monastery occupied the entire building. In the later phase, the southern part was divided into three shops, and the northern part was converted into a public kitchen, complete with an oven . At this time the kitchen probably served the adjacent hospice as well as the needs of the city’s many other pilgrims. In the second phase, only the remainder of the structure—the area between the kitchen and shops—served as the monastery itself.

In the early sixth century, a pilgrim named Theodosius visited Jerusalem and described a monastery of reclusive virgins below the southeast corner of the Temple platform, precisely where our monastery is located:

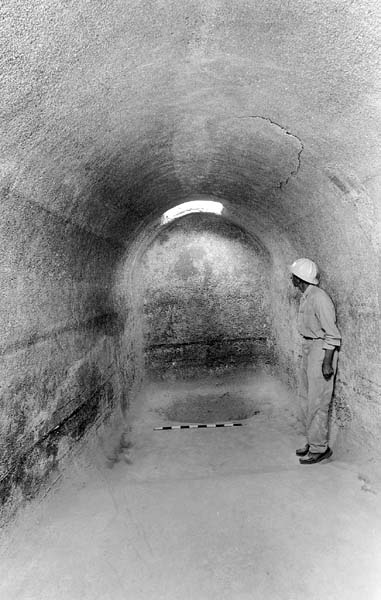

Down below the Pinnacle of the Temple [traditionally, the southeast corner of the Temple Mount] is a monastery of virgins and whenever one of them passes from this life, she is buried there inside the monastery. All their lives they never go out of the door by which they entered 032this place. The door is opened only for a nun or penitent who wishes to join the monastery, but otherwise the virgins are always shut in. Their food is let down to them from the walls, but they have their water there in cisterns.8

Our building might well be this Monastery of the Virgins.

Behind the monastery, 6 feet from the southern wall of the Temple Mount, is a vaulted chamber that served as the cellar of a structure whose ground floor was completely destroyed. The sloping floor of the vaulted chamber and a depression at the lower end would enable even the last drop of liquid to be collected from the floor. We suspect that the vaulted chamber functioned as a collection vat for wine and that the structure was the winery of the monastery, a common feature of Byzantine monasteries (and even modern ones).

A much larger two-story structure covered the area east of the monastery. Like the monastery, it is almost square, but lacks the typical Byzantine courtyard. Together with the monastery, it extended from one end of the street adjacent to the southern wall of the Temple Mount to the other, east of the monumental stairs from the Herodian period. We believe it served as a hospice for the many pilgrims visiting the city. On the ground floor, it contained 30 well-preserved rooms. The main entrance was in the northeast corner and was accessible through a long corridor. On the lintel of the inner entrance at the end of the corridor is a red painted cross. Outside an entrance on the west side is a large plastered pool. This entrance was probably for pilgrims arriving with donkeys, which were watered at the pool.

Large quantities of ash found in some of the rooms are evidence of an intense fire. The monastery was probably destroyed during the Persian invasion of 614 C.E. We have two accounts about how the Persians conquered Jerusalem that conflict with one another. One account says that the city surrendered, but the surrender was followed by a Christian uprising that was harshly crushed. The second account says the Christians resisted and refused to surrender, as a result of which the Persians besieged the city, ultimately vanquishing the defenders. In either event, the city was destroyed.

033

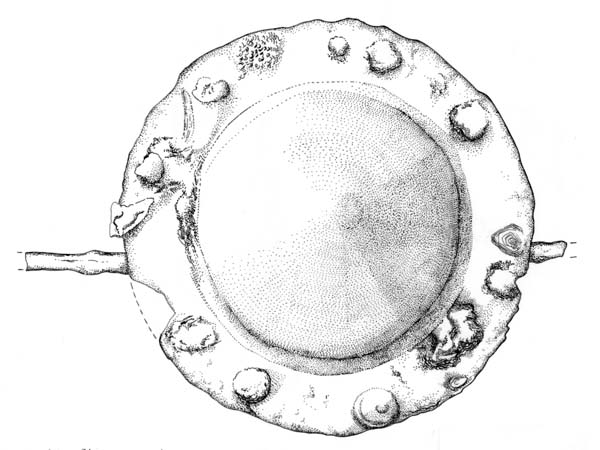

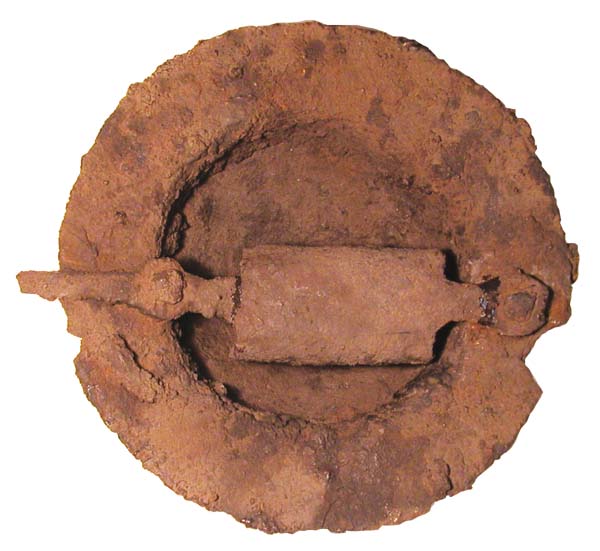

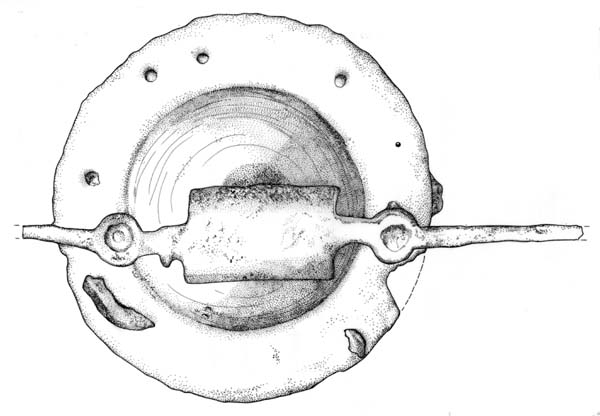

Our discoveries included reminders of the violent struggle that must have taken place here. In one room of the monastery, we found a startling military artifact—an iron umbo, or bowl-like protuberance at the center of a circular shield. A handle on the inside, across the back of the umbo, would be grasped by the user of the shield. The umbo found in the monastery still retains its gripping handle (visible in the bottom photo and drawing at right). Note that the gripping handle does not go across the middle of the back of the umbo; it is somewhat off-center. The shield holder’s fingers and wrist would be placed in the larger space, while the thumb required less room. The larger inner cavity of the umbo was doubtless at the top. The umbo served a dual purpose. In addition to providing a means of gripping the shield, the iron strip by which the umbo was attached, stretching beyond the umbo bowl, reinforced the shield’s structure.9

In an adjacent room in the monastery, we found an additional cache of military equipment, including a long sword (known as a spatha), a single-edged iron blade, a fragment from a scabbard and a pickaxe. A pickaxe had long been part of a soldier’s gear and was used both in battle and for nonmilitary activities. We are left to wonder whether these arms belonged to the Persian conquerors or to the Christian defenders.

After its destruction by the Persians, the monastery was never rebuilt. Debris covered the ruins. By luck, the monastery’s remains lay just beyond the structures built during the Islamic period; thus they were spared demolition and lay quietly for more than 1,200 years—until my grandfather uncovered them again for a new era of visitors to Jerusalem.

For ten years, between 1968 and 1978, the area south of the Temple Mount in Jerusalem was intensively excavated by archaeologist Benjamin Mazar.1 His many spectacular discoveries included the remains of a monumental staircase that led up to the southern enclosure wall of the massive platform built by Herod to support the gleaming Temple that he had luxuriously rebuilt. Mazar also found a previously unknown caliph’s palace complex from the early Arab period (late 023seventh to early eighth century C.E.), a glorious era in Islamic history that also saw the construction of the golden Dome of the Rock […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Endnotes

On behalf of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, the Israel Exploration Society and the Israel Department of Antiquities (now the Israel Antiquities Authority).

See Eilat Mazar, The Temple Mount Excavations in Jerusalem 1968–1978 Directed by Benjamin Mazar, Final Reports, vol. 2, The Byzantine and Early Islamic Periods, Qedem 43 (Jerusalem: Institute of Archaeology, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, 2003), with contributions by Donald T. Ariel, Anat Cohen-Weinberger, Leah Di Segni, Shulamit Hadad, Ya’akov Meshorer, Henk K. Mienis, Haggai Misgav, Oved Pele, Orit Peleg, Lior Shapira and Guy D. Stiebel.

I am indebted to Orit Peleg, who wrote the chapter on chancel screens in the final report, for this discussion.

John Wilkinson, Jerusalem Pilgrims Before the Crusades (Warminster, England: Aris & Phillips, 1977), p. 66.