The Shapira Scrolls, which purportedly record Moses’s last words, are 19th-century forgeries, as scholars have long maintained.a We will show this with new evidence, which has been sitting in a box first in the British Museum and then in the British Library for 140 years.

How can you tell whether a document is genuine or forged? The answer is both simple and difficult. You act like a detective—examine all the evidence meticulously and look for clues. As Sherlock Holmes says, you must “observe the small facts upon which large inferences may depend.” The clues, and the inferences based on them, combine to form a clear picture.

We will explore the evidence that proves the Shapira Scrolls are forgeries.1 But first we have to give some background, beginning with some curious events in the 1870s.

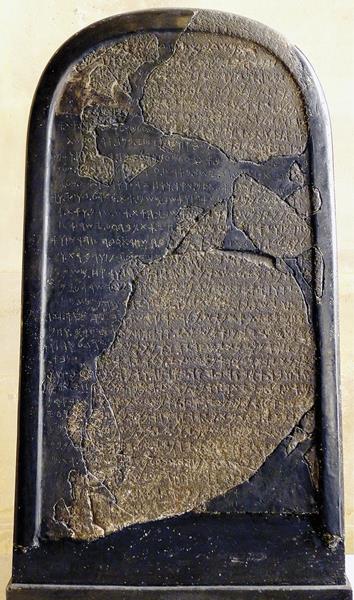

That decade was, as the late biblical scholar and epigrapher Frank Moore Cross remarked, “a season of monumental forgeries.” 2 In the years after the publication in 1870 of the ninth-century B.C.E. royal stele known as the Moabite Stone,b the antiquities market in Jerusalem was flooded with fake Moabite inscriptions and artifacts. These were available for purchase at Moses W. Shapira’s shop at what is now 76 Christian Quarter Street in Jerusalem’s Old City. Shapira sold most of his “Moabite” artifacts (some 1,700 items) to the Royal Museum in Berlin in 1875 for the princely sum of 22,000 thalers—nowadays around $250,000. Soon after, all the pieces of Moabitica were exposed as forgeries.

The Moabitica statuary is bizarre and without parallel, and the script is a strange mixture of letter forms from the Moabite Stone and the later Nabatean and South Arabian scripts. They mix scripts that are separated by a thousand years, plus imaginary forms. These paleographic reasons, alone, are enough to rule out the statuary’s authenticity. When the forgery was exposed, Shapira blamed his associate Selim al-Qari and fired him, saying, “Selim, my agent, is certainly a great rogue.” But Shapira’s antiquities business continued to thrive, and he expanded into the trade of Hebrew manuscripts.

In 1871, during the Moabite Stone excitement, Shapira presented an English visitor, Henry Lumley, with a remarkable inscribed granite stone, discovered recently in Moab and said to be from the time of Moses. According to Mr. Lumley, the learned Mr. Shapira kindly translated the text: “We drove them away—the people of Ar Moab at the marsh ground, there they made a thank-offering to God their King, and Jeshurun rejoiced, as also Moses their leader.”

Lumley noted the parallels with Numbers 21, Deuteronomy 11, and Joshua 13. He wrote excitedly to The Times of London about the discovery: “It may be, indeed, of more powerful interest than the Moabite Stone, for it contains the name of Moses, who may have directed, seen, and approved the inscription himself as a memento of the conquest of Moab by Israel.” But once back in London, Emanuel Deutsch, a scholar at the British Museum, recognized Mr. Lumley’s drawing. It was a copy of a Nabatean funerary inscription that had been recently discovered in Jordan.3

Mr. Lumley immediately wrote another letter to The Times disavowing the discovery. In this incident, Shapira was directly implicated.

Many other forgeries passed through Shapira’s shop, including the lid of the sarcophagus of Samson, which Shapira brought to London to sell in 1877. The oxidized metal lid was nearly 4 feet long and 1.5 feet wide. The inscription, written in pseudo-Moabite script, had “Samson” as its final word, written, as in the Bible, with a waw vowel letter. It was, like the Moabitica, a work of fantasy and was dismissed as an amusing forgery.

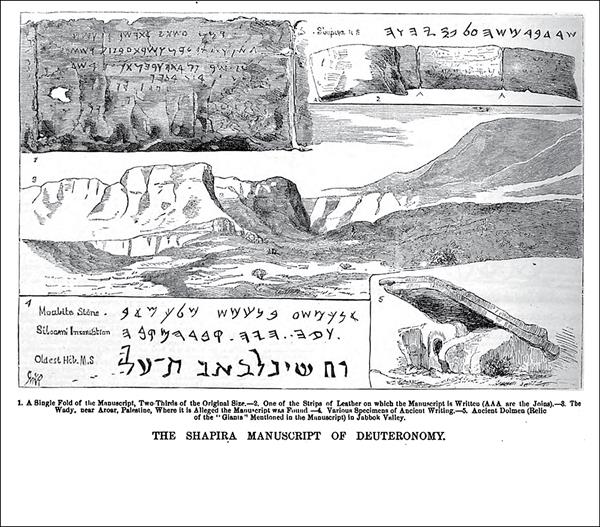

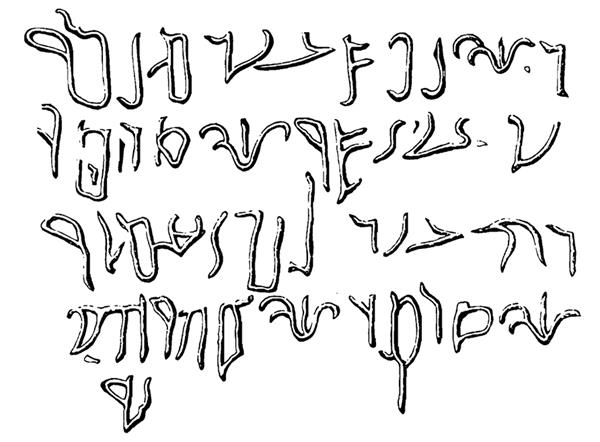

In 1883, Shapira sought to offer for sale 15 or 16 blackened manuscript fragments, which he described in a letter as “a curious manuscript written in old Hebrew on Phoenician letters upon small strips of embalmed leather and seems to be a short unorthodoxical book of the last speech of Moses in the plains of Moab.” 4 Shapira said that the manuscripts—containing two or three virtually identical versions of the text—were found in a cave in Moab, near the location where Moses gave his last speech in Deuteronomy. The text ends: “These are the words that Moses commanded to all the children of Israel by the mouth of Yahweh on the plains of Moab before he died.”

Are these authentic manuscripts of an unorthodox Deuteronomy? The scholars who examined them at the time judged them to be forgeries. One of the German scholars, Hermann Guthe, wrote a monograph examining the leather, script, spelling, and contents, in which he concluded that the manuscripts “cannot be genuine, but must be forged.” 5 A study conducted by Christian Ginsburg for the British Museum, to which we will return below, concurred: “The manuscript of Deuteronomy which Mr. Shapira submitted to us for examination is a forgery.” 6

Shapira had placed great hopes in these manuscripts. Now a broken man, in debt and humiliated, he wandered across Europe. Six months later, on March 9, 1884, he committed suicide in a hotel room in Rotterdam.

The British Museum sold the manuscripts at auction the following year for around £10 to the bookseller Bernard Quaritch. They were offered in his catalogue for £25 and acquired by Philip Mason, a surgeon and naturalist, who gave a talk about them in Burton-on-Trent in 1889. Dr. Mason died in 1903, and his wife sold all his goods. Thereafter, the Shapira Scrolls disappear from history.

After the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls some 50 years later, scholars raised anew the question of the authenticity of Shapira’s Deuteronomy. But the same conclusion prevailed—it was “a forgery.” 7 Several decades later in BAR, the epigrapher André Lemaire reached the same verdict based on anomalies in the script.c

Now the question is alive again. In March, an article in the New York Times asked a provocative question: “Is a Long-Dismissed Forgery Actually the Oldest Known Biblical Manuscript?” That week a young scholar, Idan Dershowitz, published a book and article that argue for the authenticity of the Shapira Scrolls, which he says are “a very ancient precursor to Deuteronomy.” 8 A similar argument for the manuscripts’ authenticity had been made by Shlomo Guil in 2017, but to less fanfare.9

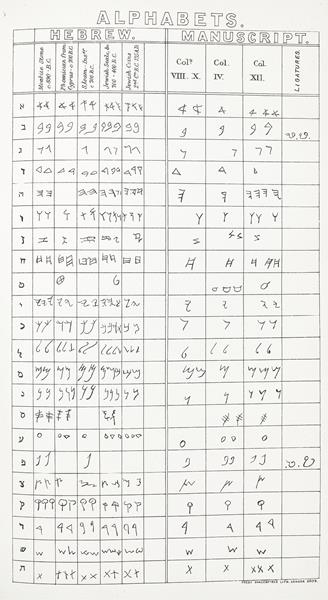

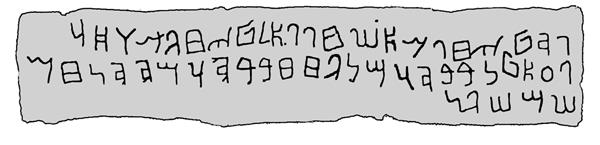

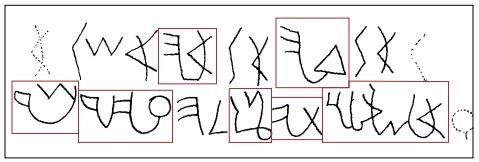

To answer the question posed by the New York Times, we present new evidence: a detailed script chart made by Ginsburg’s group for the British Museum study in 1883. It has never before been published. It includes letter forms from four columns of the Shapira manuscripts and compares them to scripts of the Moabite Stone and Phoenician and Hebrew inscriptions—the few known at the time. It agrees in its main features with the script chart published by Hermann Guthe, which attests to both charts’ reliability, according to the epigraphic standards of the time.

This chart shows that most of the letters from the Shapira manuscripts are formally similar to the letters of the Moabite Stone. If all the letters were consistent with the script of the Moabite Stone, the scrolls might be an authentic ninth–eighth century B.C.E. text. But this is not the case. Let us examine the differences of letterforms, stance, and cursive combinations.

Five letter forms clearly differ from the Moabite Stone script. The zayin (ז) looks like a zigzag (a mirrored “z”); the ṭet (ט) is circular or ovoid with one or two ticks; and the kap (כ) has a rounded head written with a single stroke coming from the top of the shaft. Other letters have odd but less obvious features, including the sade (צ), with an unusually long shaft and an oblique head, and the qop (ק), whose head is circular rather than ovoid.

None of these five letters has parallels in Old Hebrew inscriptions.d The kap is somewhat similar to forms in Hellenistic coins, as Ginsburg’s chart shows, but this would be an anachronism, an indication of forgery. Are there other parallels for these forms? Yes. All five have the same or similar forms as the fake Moabitica.

This is a strong set of clues about the origins of the Shapira Scrolls.

The second problem involves letter stance or orientation. Some letters, for instance gimel (ג), lean in the wrong direction, whereas Israelite scribes were careful and consistent in this matter. Only at the time of the Dead Sea Scrolls (from the third century B.C.E.) did the stance of gimel change.

The third problem is ligature, which is a cursive combination of two or more letters. On the script chart there are four entries, and Guthe’s chart has another one (see chart, above).

Ligatures are unknown in Old Hebrew inscriptions. But they are found in the Moabitica, which are similar to the ones in our chart. They are loosely copied from the cursive style of the Nabatean script.

The ligatures in the Shapira Scrolls, with their parallels in the Moabitica, are another mark of forgery.

Although the clues from the script are small, their implications are large. Since most of the anomalous features in the script are already found in the Moabitica, we may infer that the Shapira Scrolls depend on the fake scripts of the Moabitica or were made by the same forgers. The script is a mixture of fact (the Moabite Stone) and fantasy (the Moabitica). We may conclude that the scrolls were made not in the era of Moses or the Israelite monarchy, but in the Victorian era, during the “season of monumental forgeries.”

These paleographic discrepancies are significant. Yet Dershowitz dismisses most of the evidence from the script, since the scrolls no longer exist. But he is unable to explain how different scholars independently made charts with the same letter forms, including the unexpected forms.

He does claim, however, that some evidence from the script supports his argument. He claims that two yods drawn by a newspaper illustrator preserve features that are authentic but unknown at the time, both have a tick on the bottom, and one is written with a single stroke. But he is mistaken. The tick at the bottom right of yod was known previously, including in a drawing of the Moabite Stone by Selim, Shapira’s agent, which he used to create the fake Moabitica. Moreover, a yod with a tick is also known from a seal published in 1867 in a collection of Hebrew inscriptions. As for the single-stroke yod, Dershowitz claims there are parallels in zigzag forms discovered later, but these are debated by scholars—some have even been interpreted as numbers. So this is a weak link.

Are there other clues aside from the script? Yes. The spelling is an odd mixture of the styles of the Moabite Stone and the Hebrew Bible. Remember that Hebrew is written without vowels. The points below and above the consonants in the Hebrew Bible indicate vowels, but these signs were invented in the Middle Ages. During the Iron Age, scribes started using some consonants as vowel letters—yod, waw, and he—to indicate some internal or final vowels.

In the Moabite Stone there are no internal vowel letters. Similarly, most words in the Shapira Scrolls have no internal vowel letters. But in a handful of cases, the words do have internal vowel letters, which replicate the spelling of these words in the Hebrew Bible. According to Dershowitz’s recent critical edition of the Shapira Scrolls, internal vowel letters are found only in 11 words—a mixture of ordinary nouns, names of tribes and places, and a personal name: הוא (him/her), איש (man), נוים (nations), אות (sign), בריחן (bolts), מול (facing), יהודה (Judah), ראובן (Reuben), זבולן (Zebulun), [ש]עיר (Seir), and סיחן (Sihon).

This is an odd list. As we now know, none of these words was written with internal vowel letters in Hebrew inscriptions until the late seventh or sixth century B.C.E. These spellings are totally anomalous in an inscription written in an earlier script (not counting the fantasy forms). Prior to the seventh or sixth century, these words are always written without vowel letters, as in the following forms:

(1) הא (him; appears seven times from the mid-ninth to early sixth centuries);

(2) אש (man; appears 10 times from the mid-ninth to late eighth centuries); and

(3) יהד[ה] (Judah; appears three times from the early eighth to early sixth centuries).

By mixing earlier Moabite with later biblical spelling styles, the Shapira Scrolls have a patina of antiquity and a dash of familiarity. The same mixture of spelling styles is found in the forged Samson sarcophagus inscription—it spells “Samson” with an internal vowel letter, just as it is spelled in the Bible.

This mixture of spelling styles from hundreds of years apart yields an impossible text, written in a temporal wormhole. It is like finding a copy of the Declaration of Independence that includes emojis. The mixture of times and styles conforms to the pattern of the script, which combines ninth–eighth century B.C.E. forms with some a millennium later and others from no time at all. Similarly, the grammar is a mixture of early and late features, which, as Dershowitz admits, corresponds to no known dialect of Hebrew. These impossible mixtures are the mark of a forgery.

Dershowitz’s arguments for the authenticity of the Shapira Scrolls ignore these clues from the script and spelling. His main arguments have to do with the contents of the scrolls, which he says preserve a precursor of Deuteronomy, a text he calls the “Valediction of Moses” or “V” for short. But his arguments are mostly about omissions in the text, which on close examination do not carry weight. 10

He argues, for instance, that the text begins with an early form of Deuteronomy, since it skips from the last part of Deuteronomy 1:1 to Deuteronomy 1:6. The beginning says:

[These are the wor]ds that Moses spoke by the mouth of Yahweh to all the children of [I]srael in the wil[derne]ss, across the Jordan, [on the p]lain. Elohim, our god, spoke to [us] at Horeb, saying …

There are some differences from Deuteronomy in the shared parts of Deuteronomy 1:1 and Deuteronomy 1:6, but his point is that the omitted section is a late addition to Deuteronomy. He claims that “the version found in V is practically identical to the proto-Deuteronomic text reconstructed by scholars in recent years.” But it isn’t. The phrases “in the wilderness” and “on the plain” are part of the later expansion. The Shapira Scrolls include both the early and late compositional strata. The Shapira Scrolls know the final text of Deuteronomy, which they freely abridge.

He argues similarly that the episode where the Israelites defeat King Sihon of the Amorites lacks the late addition of Deuteronomy 2:24-37, which harmonizes the story with the rules of war in Deuteronomy 20. He says that the late section is absent from the Valediction. But he fails to observe that the Shapira Scrolls quote from this section. The Shapira text reads: “Today I shall begin to give before you Sihon.” This is a quote from the Hebrew of Deuteronomy 2:25 and Deuteronomy 2:31, which says, “Today … I shall begin to give before you Sihon.” This quote shows that this episode cannot reflect an early stage of Deuteronomy. Rather, the episode is an abridged and rewritten version of Deuteronomy, with traces of all its compositional stages.

Dershowitz extensively argues that the Shapira Scrolls do not know the Priestly layer of the Pentateuch or any of the post-Priestly expansions to Deuteronomy.e But, as others have pointed out, there are plenty of references to Priestly and post-Priestly texts in the Shapira Scrolls, including the post-Priestly expansion of the Sabbath command imported from Exodus 20, the references to Joshua from the P story of the spies in Numbers 14, the reference to the Midianites from the P story of Baal Peor in Numbers 25, and the post-Priestly expansion in Deuteronomy 2:14-16.

The scrolls also refer to the ten plagues of Exodus, which shows that their author knew the final version of the Pentateuch. Only in the final version (which combines the J and P accounts) are there ten plagues. The Shapira Scrolls say, “Surely all the people who saw my signs and my wonders that I performed ten times, but they did not believe and did not obey me.” “My signs and my wonders” is a reference to the plagues, and there are ten of them.

The Shapira Scrolls are a pastiche of Deuteronomy and other books of the Pentateuch, featuring a baroque expansion of the Decalogue, including a new tenth commandment from Leviticus 19:17 (a post-Priestly text): “You shall not hate your brother in your heart.”

If we consider all of these clues from the script, the spelling, and the content, we can say that the scholars who examined the manuscripts in 1883 were right. The many small clues and the larger inferences based on them are, we think, indisputable. The verdict is clear: The Shapira Scrolls are forgeries.

MLA Citation

Footnotes

1. Fred Reiner, “Tracking the Shapira Case: A Biblical Scandal Revisited,” and P. Kyle McCarter Jr., “Why All the Fuss?” BAR, May/June 1997; see also Jonathan Klawans, “The Shapira Fragments: An Artifact of 19th-Century Jewish Christianity,” Bible History Daily (blog), March 18, 2021.

2. Siegfried H. Horn, “Why the Moabite Stone Was Blown to Pieces,” BAR, May/June 1986.

3. André Lemaire, “Paleography’s Verdict: They’re Fakes!” BAR, May/June 1997.

4. See Matthieu Richelle, “A Very Brief History of Old Hebrew Script,” BAR, Summer 2021.

5. Victor Hurowitz, “P—Understanding the Priestly Source,” Bible Review, June 1996; Richard Elliott Friedman, “Taking the Biblical Text Apart,” Bible Review, Fall 2005.

Endnotes

1.

We are summarizing and expanding on Matthieu Richelle, “The Shapira Strips in Light of Paleography: Six Impossible Things Before Breakfast,” Semitica 63 (2021), pp. 243–294; and Ronald Hendel, “Notes on the Orthography of the Shapira Manuscripts: The Forger’s Marks,” Zeitschrift für die Alttestamentliche Wissenschaft 133 (2021), pp. 225–230. Our thanks to Idan Dershowitz for alerting us to the British Library script chart.

2.

Frank Moore Cross, “The Phoenician Inscription from Brazil: A Nineteenth-Century Forgery,” in Leaves from an Epigrapher’s Notebook (Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 2003), p. 239.

3.

This Nabatean inscription is no. 195 in Corpus Inscriptionum Semiticarum II, Tome I (Paris: Klincksieck, 1889), p. 217; see further Albert Socin, “Über Inschrift-enfälschungen,” Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft 27 (1873), 133–34 and fig. I.

4.

Letter from Shapira to Hermann Strack, Jerusalem, May 9, 1883, quoted in Fred N. Reiner, “C. D. Ginsburg and the Shapira Affair: A Nineteenth-Century Dead Sea Scroll Controversy,” British Library Journal 21 (1995), p. 113.

5.

Hermann Guthe, Fragmente einer Lederhandschrift enthaltend Mose’s letzte Rede an die Kinder Israel mitgetheilt und geprüft (Leipzig: Breitkopf Härtel, 1883), p. 77.

7.

Moshe Goshen-Gottstein, “The Shapira Forgery and the Qumran Scrolls,” Journal of Jewish Studies 7 (1956), p. 191.

8.

Idan Dershowitz, The Valediction of Moses: A Proto-Biblical Book (Tubingen: Mohr-Siebech, 2021), p. 97; Idan Dershowitz, “The Valediction of Moses: New Evidence on the Shapira Deuteronomy Fragments,” Zeitschrift fur die Alttestamentliche Wissenschaft 133 (2021), pp. 1–22.

9.

Shlomo Guil, “The Shapira Scroll Was an Authentic Dead Sea Scroll,” Palestine Exploration Quarterly 149 (2017), pp. 6–27.

10.

See Benjamin D. Suchard, “A Valediction to Moses W. Shapira’s Deuteronomy Document,” Bibliotheca Orientalis, forthcoming; Israel Knohl, “An Early Version of Deuter-onomy, or Not?” (huji.academia.edu/israelknohl); Konrad Schmid, “Is V a Literary Precursor to Deuteronomy?” and Jeffrey Stackert, “Literary Observations on Shapira Deu-teronomy and Idan Dershowitz’s The Valediction of Moses,” both from A Scholarly Webinar on Idan Dershowitz’s Recent Reassessment of the Shapira Documents, June 10, 2021.