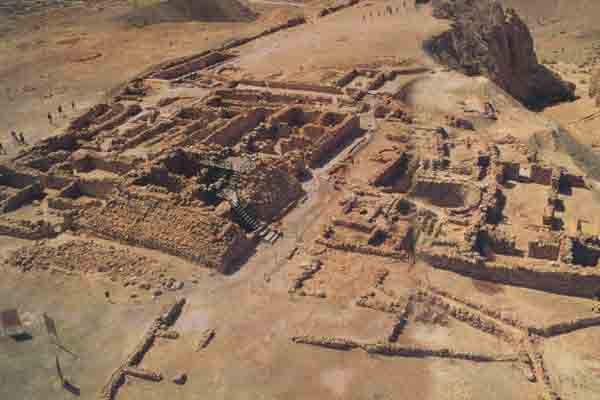

Scholars disagree about the nature of the settlement known as Qumran, which is set in the midst of the area where the Dead Sea Scrolls were found. Roland de Vaux, who directed the excavations at Qumran between 1951 and 1956, concluded that it had been inhabited by an isolated religious community, whom he identified as the Essenes. Unfortunately, de Vaux died in 1971 without completing his final report on the excavations. In 1987 a team of Belgian archaeologists, Robert Donceel and his wife Pauline Donceel-Voûte, were engaged by Father Jerome Murphy-O’Connor of the École Biblique to write the final report based on de Vaux’s notes and the excavated artifacts and remains. Although they and other scholars who joined the team have not yet finished their work, the Donceels have concluded that Qumran was not a religious comcommunity at all, but a winter villa, much like the winter villas that wealthy Jerusalemites built in the early years of this century near Jericho. The American scholar Norman Golb, on the other hand, puts forth a still different hypothesis. He argues that the site was a military fortress.a

Inextricably linked with this issue about the nature of the site is the so-called Essene hypothesis, according to which the inhabitants of Qumran were members of this small Jewish sect who broke from the Jerusalem Temple establishment and to whom the library of scrolls belonged.

Our own conclusion is that all three suggestions as to the nature of the settlement at Qumran—an isolated religious community, a winter villa or a military fortress—are wrong.

Qumran was, we believe we can show, a commercial entrepôt and a resting stop for travelers. There is no evidence that it was an Essene settlement.

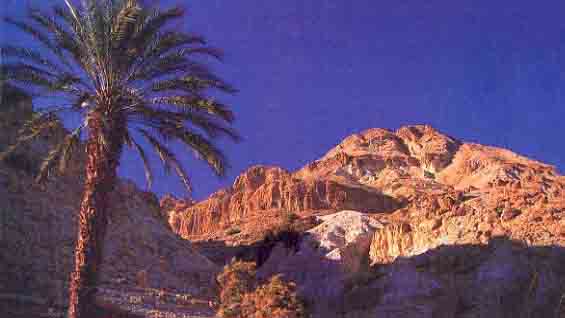

The most important single piece of evidence that might identify the site as an Essene settlement—and therefore an isolated religious community—is a passage from the Natural History of the Roman historian and geographer, Pliny the Elder (23–79 C.E.). According to Pliny, Essenes lived “on the west side of the Dead Sea, but out of range of the exhalations of the coast … [Here the Essenes] have only palm-trees for company.” Pliny then adds that “the town of Ein Gedi … lies below (infra hos) the Essenes.”1

Largely on the basis of this passage, scholars have identified Qumran as the site to which Pliny referred. But this is wrong.

De Vaux, like many scholars after him, argued that Pliny intended to describe Ein Gedi as lying south of the Essene settlement or downstream from the Jordan.2 According to this argument, the words “above” and “below” as used by Pliny are interchangeable with north and south, as is sometimes the case in the writings of contemporary historians untrained in geography. Since Pliny wrote that Ein Gedi was below where the Essenes lived, it has been taken that he meant that Ein Gedi was south of this Essene settlement.

However, these scholars have simply misunderstood what Pliny meant by “below.” He most certainly did not mean “south,” as a more thorough reading of his work will easily show. When he wanted to indicate direction, Pliny used north, south, east, south-east and the like.3 He did not use the modernisms “above” and “below” to indicate “north” and “south.” In order to describe a line of sites starting from a point of origin, but without a specific direction, Pliny would use the words “next” or “then,” not “above” or “below.” He also employed a full range of adverbs and adverbial clauses to describe locality, such as “across,” “between,” “beyond,” “on the opposite bank,” “in the middle.”

Pliny never used the word “below” (infra) for the next place in a sequence except when that place was genuinely at an altitude lower than the point described. In other words, when Pliny said “below,” he meant just that, at an altitude lower than something else. Thus, in his description of the Palmyra region, he used the term “below” to indicate that the cites of Beroea and Chalcis, in the Bekaa valley, were at a lower altitude than the Palmyra plateau. Likewise, in his description of the Black Sea district, Pliny employs the term “below” when speaking of the coastline abutting the Caucasus mountains.4

In light of Pliny’s reasonably precise use of adverbs of place, we must conclude that he meant to say only that Ein Gedi was physically at a lower level than the colony of Essenes.

Besides, Ein Gedi is about 20 miles south of Qumran, quite a distance, especially in ancient times, by which to locate the Essene colony to which Pliny was referring. For Pliny to use Ein Gedi as a site reference for Qumran would be especially odd because a number of other sites lay between Qumran and Ein Gedi.

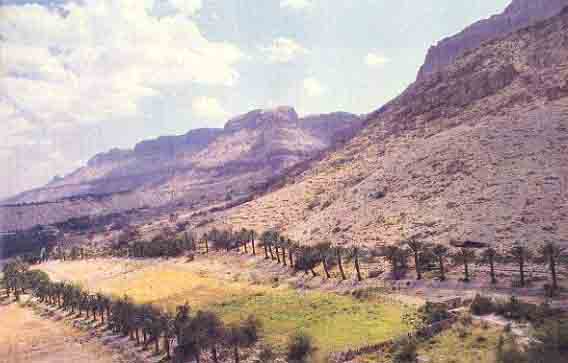

Pliny also tells us that the Essenes in this colony live among palm trees. Palm trees grow on the Dead Sea littoral where springs emerge from the hills. They do not grow on arid, bare escarpments like that behind Qumran.

The Essenes to whom Pliny was referring probably lived in the hills above the settlement of Ein Gedi, which was located on the coastal plain of the Dead Sea. At the turn of the era, Ein Gedi was the most important town and farming center on the western side of the Dead Sea. The first-century C.E. Jewish historian Flavius Josephus tells us that Essene colonies were scattered throughout Palestine.5 There is every reason to believe that some Essenes lived in or near Ein Gedi. True, there are no identifiable ruins in the vicinity of Ein Gedi to indicate that Essenes once lived there. That is what led de Vaux to look elsewhere, ultimately to Qumran. Much more likely, however, they either had a haven in Ein Gedi or lived in caves and groves above Ein Gedi.

Someday we may even find the remains of a building above Ein Gedi that served as the Essene community center. Any buildings they may have occupied would have been destroyed during the Roman occupation, however, and any nearby caves they may have lived in would doubtless have been occupied by Zealots during the First Jewish Revolt (66–74 C.E.)6 or during the Second Jewish Revolt, the so-called Bar Kokhba revolt (132–135 C.E.).

Incidentally, the 10th-century Karaiteb historian Jacob al-Kirkisani (Qirqisani) was the first to suggest that the Essenes lived in caves. Oddly enough, we find this same suggestion propounded by William F. Lynch, a 19th-century American naval officer who explored the Dead Sea by boat.c Lynch was certain that he had located caves about 600 feet above Ein Gedi where the Essenes had lived.7 Lynch located two ruins near Ein Gedi, both with adjacent caves. One, he suggested, was the home of the Essenes.

The first was “a short distance up the mountain side. It is a wall of unhewn stones without cement. The wall is on the front and two sides; the rear is the mountain side, in the face of which are several caves with apertures cut through the rock to the air above, most probably for the escape of smoke. The walls were evidently built to defend the entrance of the caves long subsequent to their excavation. The caves were filled with detritus, lime and a deposit of salt in cubes. They were perfectly dry without stalactites of any kind except the cubes of salt. The largest cave could contain twenty or thirty men and had a long narrow gallery running from one side, which would be invisible when the sun does not shine through the entrance.”8

The second site above Ein Gedi that Lynch identified may be even more likely as the local home of the Essenes. Here is how Lynch describes it:

“Some of our party had discovered in the face of the precipice, near the fountain, several apertures, one of them arched and faced with stones. There was no perceptible access to the caverns, which were once, perhaps, the abodes of the Essenes. Our sailors could not get to them; and where they fail, none but monkeys can succeed. There must have been terraced pathways formerly cut in the face of the rock, which have been worn away by winter torrents.”9

There is no published indication, so far as we know, that either of these two sites has been explored in modern times. A survey was undertaken in connection with excavations at Ein Gedi in the late 1950s and early 1960s. The 1962 excavation report states that “the Essene settlement on the terrace above Mesad Nahal Arugot is still insufficiently investigated.”10

If Qumran was not the Essene colony Pliny referred to, who lived at Qumran? And what was Qumran?

Scholars have relied not only on Pliny’s text, but also on the text of the scrolls to support the identification of Qumran as an Essene settlement. And it is true that we find a general similarity between the doctrines preached by the Essenes as recorded by Philo, Josephus, Solinus, Hippolytus, Porphyry and Epiphanius, on the one hand, and the traditions described in the scrolls found in the 11 Qumran caves, on the other. But it is not the similarities between Essene ideas and the ideas in the scrolls that matter; it is the differences that are significant. Everything we know from the ancient sources tells us that there must have been basic similarities between all the “philosophies” of Judaism at the time, because they were all branches of a common trunk, the Biblical precursor of Judaism. Thus, the similarities between the scrolls and the teachings of any of the philosophies are meaningless because they show only that they relate to the common trunk. It is the details in which the “philosophies” differ from each other that matter. And in these details we find that Essene and Qumran traditions differ significantly, as a result of which we must conclude that the scrolls are not the products of the Essenes.

If we were to consider only similarities, we might conclude that the scrolls were produced by the Rechabites, Samaritans, Ebionites or Sadducees. The name Essenes, incidentally, never appears in any of the scrolls.

Let us look at some of the Essene characteristics as reflected in the ancient literature about them, on the one hand, and what we find in the scrolls and in their alleged settlement at Qumran, on the other:

• The Essenes are depicted as peace-loving11 and are said not to have manufactured weapons. The ruins of Qumran, however, include a fortified tower, burnt, mined and partially destroyed in what must have been a siege, fiercely resisted by fighting men.12 Moreover, the Qumran scrolls do not reflect peace-loving traits, but warlike characteristics,13 with their many references to war (albeit at a future date), the particulars of army organization and detailed descriptions of weapons.14 From the accounts in the scrolls, it can be inferred that their writers included skilled tradesmen and craftsmen, capable of forging and decorating magnificent weapons; these can hardly be the same people as the primarily agriculturalist Essenes.

• Some ancient sources claim that the Essenes were celibate, living without women (although Josephus states a small group did marry).15 The scrolls, on the other hand, contain a great number of rules for the conduct of women,16 and of men toward both women within the community and women who were not members of the community.17 The scrolls also contain some rules affecting children.18 Why would a predominantly celibate male sect need so many rules about the opposite sex if they were excluded from their community? Moreover, both female and child skeletons were found in the Qumran cemeteries.19

• The Essenes are said to have detested slavery;20 the keeping of slaves was specifically forbidden21 Yet the scrolls do not even hint that the keeping of slaves was forbidden. On the contrary, instructions for their treatment are set out.22

• The Essenes scorned wealth and its trappings23 Would they have possessed the valuable artifacts found at Qumran—for example, the high quality stone vessels imported from Jerusalem, or the luxurious glassware found in the ruins in considerable quantities?24

• According to the ancient literary sources relating to the Essenes, they did not swear oaths;25 they apparently took the position that they habitually spoke the truth and their simple word was sufficient. Oath-taking was demanded only on the occasion of their joining the sect.26 The Scrolls, however, require an annual oath of adherence to the community.27 They also contain many rules governing other occasions when oaths were required and the status of persons whose oaths were binding or could be canceled.28

• The Essenes, we are told, did not own private property. They had to hand over their possessions upon joining the community.29 The scrolls are not uniform in this matter. The writer of the Community Scroll demanded that the prospective member must hand over his property after a year’s novitiate, yet even in this scroll some rules indicate that members had to make good certain losses from their own pockets; others were required to pay only a small monthly contribution to charity. But they were allowed to hold personal property as long as it was justly acquired.30

Perhaps the most significant factor that militates against the identification of Qumran as an Essene settlement is the nature of the settlement itself, which brings us back to de Vaux’s suggestion that it was an isolated religious community and the counter-suggestions that it was a winter villa or a military fortress. It is, we believe, none of these. Rather, its full geographical context suggests it was a commercial entrepôt.

This conclusion, if correct, conflicts with the identification of the site as an Essene settlement. The Essenes are described as a community that lived chiefly through agriculture and craft31 They abhorred the idea of commerce and would have striven to be self-reliant for food. As earlier noted, with “only palm trees for company,” they lived an isolated life.

By contrast, we shall see that the inhabitants of Qumran failed to use nearby agricultural fields, they lived on a major trade route with constant comings and goings, they constructed a highly sophisticated water system for commercial purposes that took skill and capital and, as already mentioned, they had no palm trees.

Just west of Qumran is an area known as the Buqei’a, where crops were produced in the Iron Age II (ninth-sixth centuries B.C.E.). Three ancient farming settlements, Khirbet Abu Tabaq, Khirbet es-Samrah and Khirbet el-Maqari, were investigated by Frank M. Cross, J. T. Milik,32 and Lawrence E. Stager.33 They called these ruins “village fortresses” that protected the agricultural land of the Buqei’a. These sites were not inhabited and the land was not farmed, however, during the Hasmonean and Hellenistic periods (Strata Ia, Ib and II at Qumran). If the inhabitants of the Qumran settlement were Essenes during these periods, we would expect them to have farmed this land. Instead, the inhabitants of Qumran apparently purchased their food from elsewhere. (Grain storage facilities were reportedly found below the plateau of the Qumran settlement, in a recent excavation [part of Operation Scrolld] by Israel Antiquities Authority Director Amir Drori and district archaeological officer Yitzhak Magen.) This certainly doesn’t sound like an Essene settlement.

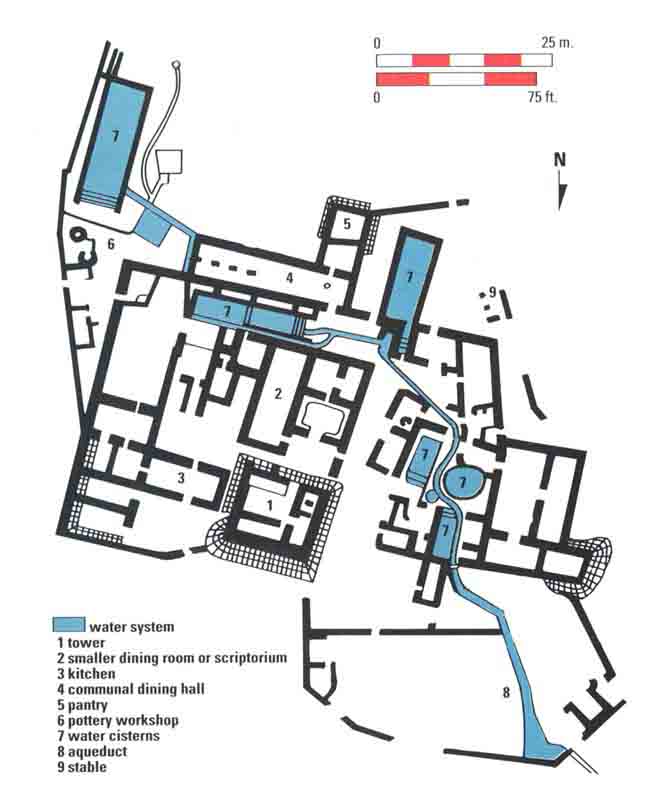

Qumran boasted an elaborate, highly sophisticated water system, which ensured the availability of water even over a number of exceptionally dry seasons. The construction of this system was a considerable hydrological engineering feat. It appears unlikely that such a major project could have been undertaken with the meager material resources and civil engineering capabilities of the Essenes.

A great number of coins were recovered at Qumran, much more than the number usually found at Second Temple settlements. The same is true of Ein Feshka, the settlement associated with Qumran on the shore of the Dead Sea. This reflects the kind of commercial activities that we would not expect from the Essenes, who, according to Philo, were farmers, shepherds and craftsmen. Now let us look at the geographical context of Qumran.

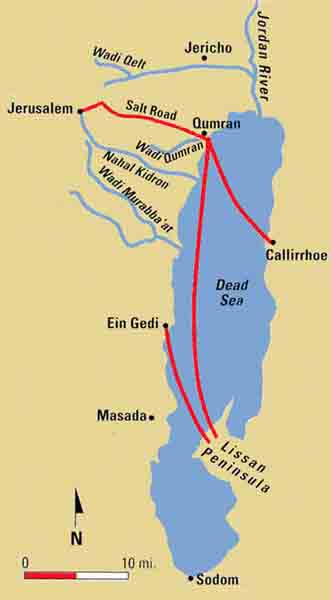

In ancient times the Dead Sea itself was a trade route, a sea dead to life under its waters but very much alive with traffic on its surface. The very nature of its water made it commercially advantageous since it could support loads far greater than those normally carried on vessels in open waters. For 37 to 50 miles (depending on its water level),34 it fills part of the Rift Valley and cuts the cross-country routes from the Mediterranean coast to Jordan and Arabia at the critical node where Jerusalem stood. Traffic either had to skirt the Dead Sea or use a “shortcut”—the surface of the sea itself. Heavy goods could be transported speedily by oar and sail-propelled craft from ports of the western shore, such as Qumran and Ein Gedi, to the ports on the eastern shore, like Callirrhoe and Lissan. The Dead Sea figures prominently on the famous sixth-century Madaba map, which displays two boats sailing on it. At times, when the high level of the lake lapped against the escarpment, travelers and traders had virtually no alternative but to use the sea route because the coastal route would have been impassable.35

Considerable commerce was also generated from materials produced in this area. The sea itself produced bitumen (asphalt), which was gathered by boat and carried long distances by land.36 In 312 B.C.E. a naval battle was fought on the Dead Sea when Antigonus of Syria tried to seize control of the asphalt trade.37 Salt was another major item of trade, either mined as rock salt near Sodom or extracted through the evaporation of brine in evaporation ponds.

The Dead Sea shore supported agriculture, animal husbandry and hunting. New studies suggest that the climate 2,000 years ago in this area was moister than it is now, so that areas then capable of supporting agriculture would have been rather more extensive than today. An archaeological survey indicates that coastal settlements and settlements along the routes from the Dead Sea coast inland and around the fresh water springs were quite numerous.38

Of especial concern and great value was the trade in frankincense and myrrh. Frankincense in considerable quantities was required by the Jerusalem temple, where it was used on the altars and eaten by the priests. Myrrh was needed in the Ein Gedi-Qumran region to blend with balsam, herbs and anointing oil for the production of cosmetics, perfumes and medicaments for which the region was famous. Since all the frankincense and myrrh were produced in Arabia and the Horn of Africa,39 their transhipment would have followed the most convenient route to Ein Gedi and Jerusalem, that is, first, up the eastern side of the Ghor (the flatland south of the Dead Sea) and then across the Dead Sea by boat from the eastern ports.40

Qumran, strategically sited, must have been an important node in this trade network. The remains of a wall that may well have served as a wharf for Qumran have been found alongside the outlet of the Wadi Qumran, close to the main ruins on the terrace above.41 Part of this wall is visible in early aerial slides of Qumran taken by Richard Cleaves along the ancient wadi bank, next to what appears to be an unexcavated area, but which may be the remains of a modern camp. So far as one can tell from the orientation and aerial photographs, this wall—or wharf—was built along the ancient strandline, the former shoreline above the present water level. It is now well above the water line, for the sea level has dropped considerably, as at least 30 ancient and modern strandlines testify. The actual drop appears to be between 65 and 80 feet.42

If this wall was in fact part of a wharf, this would indubitably point to Qumran as a port, transit center, entrepôt and perhaps an industrial site for manufacturing salt in drying pans, with a garrison troop community, and the commercial outport for Jerusalem and Jericho. Even without such a wharf facility, when the sea level was elevated the wadi mouth would have provided reasonable anchorage.

A direct route exists between Qumran and Jerusalem, linking the shore of the Dead Sea to the Holy City via a breach in the cliff line at the Wadi Qumran.43 Although no wheeled vehicle—not even a cart—could have managed this track, camels and pack-asses would have had no difficulty. It was far less steep and less circuitous than other well-known and well-traveled roads, such as the Ma’ale Aqrabbim, from the Arabah to the Judean hills.44

Salt was particularly important because the salt trade was controlled by monarchs who collected a substantial salt tax.45 Qumran was probably an important toll and tax collection point for the salt trade, and the route from Qumran to Jerusalem may have been known as the Ma’ale Hamelach, the Salt Ascent (route), or the Salt Road. This name was first given to the route by Israeli scholar Menashe Harel.46 Harel reasoned that this route constituted the shortest and most economical way to transport salt from the southern Dead Sea mines at Usdum (believed to have been Sodom) to Jerusalem, particularly if water transport on the Dead Sea was employed.

In sum, the Dead Sea valley was part of an important trade route and also an important source for the production of salt, balsam, perfume and asphalt. That part of the trade coming from the southeast and bound for the largest market in the region, Jerusalem and its all-consuming sacrificial altars, would cross the Dead Sea through one of the eastern ports and then be reloaded for transport by land either at Qumran or Ein Gedi. The shortest land route to Jerusalem would certainly have been up the Derekh Hamelach, the Salt Road, from Qumran.

If this is true, what we would expect to find at Qumran is a way-station, entrepôt and customs post on the trade routes between the Dead Sea and Jerusalem. It would almost certainly include an inn at which a large number of travelers could be fed. We would expect to find a fortress-tower to protect the route and collect tolls and a cemetery for those who died en route.

This is precisely what we find at Qumran: a number of buildings situated on top of an escarpment overlooking the roads coming up from the Dead Sea and down from Jerusalem. A fortified tower protected the main entrance at the northern side of the settlement. No access could be gained to the tower from the ground floor, but only by way of an easily defended, first-floor entrance. Another feature of the settlement was the number of large rooms for feeding travelers complete with utensils suitable for eating and drinking. On the other hand, there were very few small living quarters, as little such accommodation was needed for passing caravans or travelers on their way to and from Jerusalem.

De Vaux himself noted certain manufacturing facilities at the site. Besides the pottery workshop there were two other small industrial sites that de Vaux was not prepared to identify.47 Since then a number of suggestions for the use of these workshops have been made, including the dyeing of cloth and a smithy for repairing weapons or tools. Recently, Pauline Donceel-Voûte suggested that the shallow basins and the heating system may have been used for macerating herbs and aromatic plants for the preparation of perfume.48 This hypothesis would fit the Donceels’ conclusion that Qumran was some kind of villa rustica that included small-scale industries.

The most difficult room to interpret is what de Vaux called the scriptorium (his locus 30), where the scrolls were supposedly copied. De Vaux reached this conclusion on the basis of inkwells he found there and installations he interpreted as desks. As early as 1959, Henry E. Del Medico interpreted this locus as a dining room or triclinium.49 Godfrey R. Driver in the next decade also favored an upper floor dining room.50 Presumably the “tables” (de Vaux’s desks) fell from the upper story that did not survive. Driver pointedly noted that, according to Mark 14:15, the “Last Supper” occurred in a large upstairs room.

The Donceels too now interpret locus 30 as having contained an upper story that served as a coenaculum—that is, a place for a small number of diners who took their meals in the Hellenistic manner, reclining on couches. According to the Donceels, the installations initially interpreted as desks with benches (an interpretation now universally abandoned; ancient writers did not use desks),51 and later as tables and still later as benches with footrests, were in fact platforms that ran around three walls of the room supporting the larger structures or dining couches. This left open one side of the room for the occupants to enjoy the view toward the south and catch any breeze from the Dead Sea.52

Dining while sprawled on couches was a mark of elegance and social class in the Hellenistic world. It was so well entrenched in Hellenistic Judaism, even in Palestine, that it became an accepted part of the Passover evening ritual: Everyone at the Passover table (the seder) is to recline. One of the questions the youngest child at the seder asks even today is why everyone reclines at this meal. Moreover, the custom was hardly new. As early as the eighth century B.C.E., Amos excoriated the wealthy and the wicked: “Sprawling on their divans, they dine on lambs” (Amos 6:4 [New Jerusalem Bible]).

As for the inkwells, the Donceels argue that they did not fall from the upper story, but were originally located on the ground floor.53 These inkwells suggest that the ground floor was used to take orders and maintain records regarding the running of the establishment. These were written by scribes in the lower chamber on behalf of the owners or overseers.

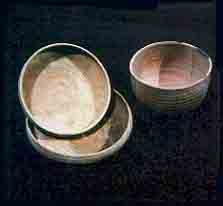

That locus 30 was a dining room rather than a scriptorium does not conflict with de Vaux’s identification of the largest room in the settlement (locus 77) as a dining room. Actually, de Vaux called locus 77 a “refectory,” using the name for the dining room in medieval monasteries, this one supposedly where the monk-like inhabitants of Qumran ate their communal meals. Adjoining this impressive long room was a “pantry” with thousands of crude, locally made bowls and dishes, which supposedly confirmed the identification.

There is no reason to doubt the identification of this locus as a dining room. Locus 30 was for the “quality” customers, while locus 77 was the large communal dining room for the workers, merchants and other visitors to Qumran. As for the large quantity of pottery in the pantry, this was simply the kitchen inventory of an inn.54

Another significant find not often mentioned in this connection is a substantial hoard of Tyrian half-shekels55 of the type favored for contribution to the Temple by diaspora Jewry.

All in all, the evidence indicates that Qumran was not an Essene settlement but a customs post, entrepôt for goods and a resting stop for travelers crossing the Salt Sea.

The obvious question that then arises is, what about the scrolls? What was the relationship of the scrolls to the settlement?

We believe they were brought from elsewhere for safekeeping either as an emergency measure or for deposit. In either case it would have been logical to transport them in their original wrappers and take advantage of the pottery at Qumran. This would explain the findings of similar pottery shapes in both the caves and at the settlements of Qumran and Ein Feshkha. The custom of hiding precious possessions in the many caves in the cliffs and wadis on the western side of the Dead Sea probably originated in Chalcolithic times (fourth millennium), when a huge treasure, which appears to have been ritual objects, was hidden in a cave in Nahal Mishmar.e Other caves in Wadi ed-Daliyeh were hiding places for Samaritan records from the third century B.C.E.f; the caves at Wadi Murabba’at and Nahal Hever hid letters from Bar Kokhba, as well as archives and treasures from the Second Jewish Revolt, the Bar Kokhba war (132–135 C.E.).g The depositing of scrolls in the caves around Qumran simply followed an old tradition.

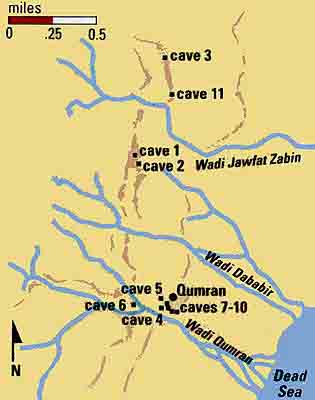

Moreover, not all the so-called Qumran caves were in the immediate vicinity of the Qumran settlement. Cave 3, where the famous Copper Scroll was found,h is one and a quarter miles north of the Qumran settlement. So is Cave 11, one of the richest caves, which included a major Psalms scroll and the Temple Scroll, the longest of the scrolls.i

Some of the Qumran scrolls could have been placed in the caves as a genizah, where worn-out scrolls were given a final resting place and where controversial or heretical scrolls were also stored. Another possibility, of course, is that the scrolls were hidden at a time when the Roman conquest of Jerusalem was imminent.

In short, Qumran was not an isolated religious community of Essenes and the scrolls should no longer be regarded as reflecting Essene doctrine.

MLA Citation

Footnotes

See Hershel Shanks, “The Qumran Settlement,” BAR 19:03; Shanks, “Blood on the Floor at the New York Dead Sea Scroll Conference,” BAR 19:02; Stephen Goranson, “Qumran—The Evidence of the Inkwells,” BAR 19:06.

The Karaites are a sect of Jews established in late classical to early medieval days with an alleged connection to the Sadducees.

See Emanuel Levine, “The United States Navy Explores the Holy Land,” BAR 02:04.

See “Peace, Politics and Archaeology,” BAR 20:02.

See Joseph Patrich, “Hideouts in the Judean Wilderness,” BAR 15:05.

See Paul W. Lapp, “Bedouin Find Papyri Three Centuries Older Than the Dead Sea Scrolls,” BAR 04:01, and Frank Moore Cross, “The Historical Importance of the Samaria Papyri,” BAR 04:01.

See Amos Kloner, “Name of Ancient Israel’s Last President Discovered on Lead Weight,” BAR 14:04.

See Manfred R. Lehmann, “Where the Temple Tax Was Buried,” BAR 19:06, and James E. Harper, “26 Tons of Gold and 65 Tons of Silver,” BAR 19:06.

See Yigael Yadin, “The Temple Scroll: The Longest And Most Recently Discovered Dead Sea Scroll,” BAR 10:05.

Endnotes

Pliny the Elder, Natural History 5.15.73 (vol. 2, p. 73), trans. H. Rackham, Loeb Classical Library (Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univ. Press, 1952).

Père Roland de Vaux, Archaeology and the Dead Sea Scrolls (London: Oxford Univ. Press, 1973), pp. 133–135.

See his descriptions in Natural History, immediately before his description of the Essenes, at 5.20.83–85.

“They are not in one town only, but in every town several of them form a colony … ” Josephus, The Jewish War 2.124, trans. H. St.-J. Thackeray, Loeb Classical Library (London: Heinemann/Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univ. Press, 1976).

See William F. Lynch, Narrative of the United States’ Expedition to the River Jordan and the Dead Sea (Philadelphia: Lea and Blanchard, 1849; New York: Arno Press, 2nd ed., 1977). Lynch does not give this height. One has to correlate his description with the statement of Claude-Regnier Conder and H. H. Kitchener in The Survey of Western Palestine, (London: Palestine Exploration Fund, 1883), vol. 3, p. 384.

Lynch, Narrative of the United States’ Expedition, p. 289. This site is at or close to Ras al Muqqadam (Map reference 1:100,000–1855/1001).

Lynch, Narrative of the United States’ Expedition, p. 294. From the general description of the camp pitched by Lynch, a half mile south of the spring but “immediately in line with, but some little distance from where the fountain stream of Ain Jidy descends the mountain side” (p. 289), we can see that the “Essene caves” were on the southeastern side of the scarp slope of the Shakarat an Najjar (1:100,000–186096), that is, on the northwestern scarp face of the Nahal Arugot.

Benjamin Mazar and Trude Dothan, “The History of the Oasis of En-Geddi,” Atiqot 5 (1966), pp. 1–12, note 19.

“In vain would one look among them for makers of arrows, or javelins, or swords, or helmets, or armour, or shields; in short, for makers of arms, or military machines or any instrument of war, or even of peaceful objects which might be turned to evil purpose.” Philo, Quod omnis probus liber sit, in Complete Works, trans. F.H. Colson et al., 10 vols. (London: Heinemann, 1929–1961), p. 78.

Particularly in the War Rule scroll from Caves One and Four (1QM, 4QM), which describes the battle of the “Sons of Light” against an enemy called the “Kittim,” and the Temple Scroll from Cave Eleven (11QT), which encourages the king to make war against the enemies of his country and gives rules about slaying enemies and taking captives.

“The formation shall consist of one thousand men ranked seven lines deep, each man standing behind the other” (1QM 5.3–4). “In their hands they shall hold a spear and a sword. The length of the spear shall be seven cubits … The swords shall be made of pure iron refined by the smelter and blanched to resemble a mirror … ” 1QM 5.5–16 (Geza Vermes, trans., The Dead Sea Scrolls in English [Harmondsworth, England: Penguin, 1990]).

Philo, Apologia pro Judaeis 14–17: “[T]hey banned marriage at the same time as they ordered the practice of perfect continence”; Pliny, Natural History 5.15.73: “[They live] … without women, and renouncing love entirely” Josephus, War 2.120–121: “They regard continence and resistance to passion as a virtue, they disdain marriage for themselves … It is not that they abolish marriage … but they are on guard against the licentiousness of women”; and see 2.160–161: “There exists another order of Essenes who, … are separated from them on the subject of marriage.”

“ … [T]hey shall summon them all, the little children and the women also, and they shall read into their ears the precepts of the Covenant … ” Messianic Rule (1QSa). There are also special rules for women in the Temple Scroll (11QT) corresponding to the rules found in the Pentateuch, as well as similar ones in the Damascus Rule (CD) and in fragments from Cave Four. For a full treatment see L. Cansdale, “Women in the Dead Sea Scrolls,” Proceedings of the 11th Conference for World Jewish Studies (Jerusalem: World Union of Jewish Studies—Magnes Press, June 1993, in press).

“A man may marry a beautiful captive woman, but he must first let her mourn a month for her parents.” Temple Scroll (11QT) 63.11–15.

“From [his] youth they shall instruct him in the Book of Meditation and shall teach him according to his age … for ten years.” Messianic Rule (1QSa) 1.6–8. See also Temple Scroll (11QT) 62.9–10: “[When an enemy city is captured] … you shall put all males to the sword, but the women, the children … you may take as spoil for yourself.”

De Vaux, Archaeology and the Dead Sea Scrolls, pp. 57–58; S. H. Steckoll, Preliminary Excavation Report in the Qumran Cemetery Revue de Qumran 6:23 (1968), pp. 323–336.

Josephus, Antiquities 18.21: “They acquire no slaves; in fact they consider slavery an injustice.”

Philo, Quod omnis probus liber sit, 79: “There are no slaves among them, not a single one … and they condemn slave-owners … in that they transgress the law of nature.”

“No man shall chide his manservant or maidservant or laborer on the Sabbath” (Damascus Rule [CD] 11.12). “[H]e shall not sell them [the Gentiles] his manservant or his maidservant” (CD 12.10).

Josephus, War 2.122: “They despise riches … in vain would one search among them for one man with a greater fortune than another”; Philo, Apologia pro Judaeis 4: “None of them can endure to possess anything of his own,” and 11: “All of them loving frugality and hating luxury as a plague for body and soul.”

Robert Donceel, “Reprise de travaux de publication des fouilles au Khirbet Qumran,” Revue Biblique 99:3 (1992), pp. 557–573.

Essenes show their love of God “by rejection of oaths,” Philo, Quod omnis probus liber sit 84; and see Josephus, War 2.135: “Every word they speak is stronger than an oath and they refrain from swearing, considering it worse than perjury.”

Josephus, War 2.139–142: “He makes solemn vows before his brethren. He first swears to practice piety towards the Deity … ”

The Temple Scroll (11QT 53.16, 54.5) rules as to when a husband or father can cancel a woman’s oath and when it may remain in force. Similar ordinances appear in the Damascus Rule (CD 14.10–12).

Philo, Apologia pro Judaeis 4: “None of them can endure to possess anything of their own”; and Quod omnis probus liber sit 86: Whatever they receive as salary … is not kept to themselves, but it is deposited before them all”; Josephus, War 2.122: “It is the law that those who enter the sect shall surrender their property to the order.”

Community Rule (1QS) 6.19: “ … his property and earning shall be handed over to the Bursar.” 1QS 7.6–8: “But if he has failed to care for the property of the Community, thereby causing its loss, he shall restore it in full.” Damascus Rule (CD) 14.13: “They shall place the earnings of at least two days out of every month into the hands of the guardian … and from it they shall succour the poor and the needy … ” and CD 6.15–17: “They shall separate from … the unclean riches from the Temple treasure … to make of widows their prey … ”

Philo, Quod omnis probus liber sit 76: “Some Essenes work in the fields, others practice various crafts contributing to peace.” Philo, Apologia pro Judaeis 8: “There are farmers among them, experts in the art of sowing and cultivating plants, shepherds leading every sort of flock, and beekeepers. Others are craftsmen in diverse trades”; Josephus, Antiquities 18.19: “They are excellent men and wholly given up to agricultural labor.”

Frank Moore Cross and J. T. Milik, “Exploration in the Judean Buqeah” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 142 (1956), pp. 5–17; Cross, “A Footnote to Biblical History,” Biblical Archaeologist (BA) 19/1 (1956), pp. 12–17.

“Ancient Farming in the Judean Wilderness,” BAR 03:03; Lawrence E. Stager, “Farming in the Judean Desert during the Iron Age,” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 221 (1976), pp. 145–158.

In addition to the geographical literature cited below, see Arie Nissenbaum, “Shipping Lanes of the Dead Sea,” Rehovot 11:1 (1991), pp. 19–24.

Within the last ten years, substantial research has taken place by members of the Deutsche Evangelische Institut für Altertumswissenschaft under the direction of A. Strobel at ancient Callirrhoe, virtually southeast of Qumran but on the eastern shore, which was long maintained as a harbor; Callirrhoe was the logical port for transhipment of goods to and from Qumran. An ancient road from Callirrhoe to the Wadi Zerqa Ma’in was bordered by watchtowers. Callirrhoe itself was rebuilt by Herod as a luxurious resort place with villas, thermal springs and a harbor. The latter must have handled passengers as well as goods, as this was the easiest route from Jericho and Jerusalem to Machaerus. Roman roads linked Callirrhoe, Zerqa Ma’in and the eastern overland route, the Kings Highway and the Derekh Hamelach.

Other Dead Sea harbors appear to have been at Minet el Mazra on the north of the Lissan peninsula, at Ein Gedi, Ma’aganit Hamelah and Kallia. Survey results in the southern Ghor show that there was a well-developed road network with Roman customs posts that testifies to a heavy overland trade along the full length of the eastern side of the Wadi Araba, linking up with the network from Callirrhoe. (We are indebted to an unpublished article of a member of the research team for this information.)

The evidence from ancient sources is examined in Nissenbaum, “Shipping Lanes of the Dead Sea,” p. 22.

Pessah Bar-Adon, “Excavations in the Judean Desert,” Atiqot 9 (1989), Hebrew Series 1–91. See map opposite p. 1.

This trade is described by G. van Beek, “Frankincense and Myrrh,” BA 2 (1964), pp. 99–126. See also J. Innes Miller, The Spice Trade of the Roman Empire, 29 B.C.–A.D. 641 (Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, 1969), pp. 102–105.

We can trace the movement of these products as far as Petra in the writings of Strabo. Since some of it ended up in Gaza, according to Pliny, we can only assume that a transhipment took place across the Dead Sea. Strabo, Geographia 16.4.24, and Pliny, Natural History 12.32.63–64.

Some people who have had access to de Vaux’s notes suspect he was well aware of the remains of the wall and had recorded its existence in his notes but did not mention it in his publications. This wharf is also apparently recorded as 350-meter, NW-SE oriented, remains of a wall in the 1967–1968 Judea-Samaria-Golan survey published in 1972. Ed. Moshe Kochavi, Judaea, Samaria and the Golan, Archaeological Survey 1967–1968 (Archaeological Survey of Israel, Jerusalem, 1972). See also Lawrence E. Stager, “Farming,” p. 157.

For the ancient evidence, see Ellsworth Huntington, Palestine and its Transformation (London and New York: 1911), chap. 14, “The Fluctuations of the Dead Sea,” especially pp. 318–319. For the modern evidence, see the discussion of the hydrology in the Atlas of Israel, “Hydrology” and Cippora Klein, “On the Fluctuations of the Level of the Dead Sea Since the Beginning of the Nineteenth Century” (Hydrological Paper no. 7, 1961, revised 1965). The Dead Sea would have been of considerably greater length than it is now, as Huntington’s discussion of possible seacoast sites testifies.

The Israelite and Roman sites between Qumran and Feshka, as indicated by the reasonably precise map references in the Judea-Samaria-Golan survey, seem to be on the same level above the water, between the -375m and the -350m contours. This would place them close to the water’s edge. In other words, the shore line was between the -375m mark and its present level. The sea height, as suggested, would have allowed the mouth of Wadi Qumran to provide some security from the sudden squalls to which the Dead Sea is prone.

From there, it runs inland along a relatively straight track to the khirbet at Zarzniq (1:100,000–18561270); then the track turns south along the relatively unbroken slope to Khirbet el Muntar on what 19th-century travelers described as the old Jerusalem road, which turns northeast to enter the city via the Kidron valley. Information on this routeway is difficult to find but is described by some of the 19th-century travelers. See, for example, Cunningham Geikie, The Holy Land and the Bible (London, Paris, New York and Melbourne: Cassell, 1887), vol. 2, p. 131. The road is shown without a name in Menashe Harel, “Israelite and Roman Roads in the Judean Desert,” Israel Exploration Journal 17:1 (1967), pp. 18–25. Subsequently, Harel named the road the “Salt Road.” “The Route of Salt, Sugar and Balsam Caravans in the Judean Desert,” GeoJournal 2:6 (1976), pp. 549–556. This route is an alternative to the Ma’ale Adumim, which carried traffic to the city of Jericho.

See also M. Harel, “The Roman Road at Ma’aleh ‘Aqrabbim (Scorpions’ Ascent),” Israel Exploration Journal IX:3 (1959), pp. 175–179, and John Rogerson, The New Atlas of the Bible (London: Guild, 1985), p. 114.

The only time we hear of the tax being suspended was during the reigns of Demetrius of Syria and Alexander Balas, when those kings sought to curry favor from Jonathan around 160 B.C.E. (1 Maccabees 10:28–30).

Pauline Donceel-Voûte, in a transcript of the BBC Horizon television series Resurrecting the Dead Sea Scrolls, Teresa Hunt, producer. Text adapted from program transmitted March 22, 1993, pp. 22–23.

Godfrey R. Driver, “Myths of Qumran,” Annual of Leeds University Oriental Society 6 (1969), p. 26.

Pauline Donceel-Voûte, “Coenaculum—La salle á l’ètage du locus 30 á Khirbet Qumrân sur la Mer Morte,” Res Orientales 4 (1992), p. 65, illus. 7.

A parallel may be found at the Iron Age extramural quarter of Jerusalem where the excavators found a “tumble of pottery” in a cave. This pottery consisted of a great number of small bowls, “probably used for drinking wine … juglets, which could have been used for keeping oil, … [and] other pottery connected with cooking and serving food.” This Iron Age find was, according to the excavators, a “kitchen inventory of a restaurant or guest house.” H. J. Franken and M. L. Steiner, Excavation in Jerusalem 1961–1967: The Iron Age Extramural Quarter on the South East (Oxford: 1990), pp. 24–27, plate 6.