Digs 2020: 8 Stops in Northern Israel

024

Archaeological sites abound in the Levant. These ruins, many of which are currently being excavated, range in size and settlement type. Yet most contain architectural remains, pottery, texts, and artifacts, as well as bones and botanical remains. All these pieces fit together to paint a picture of ancient life and civilization.

When you participate in an archaeological excavation, you help bring these materials to light. The excavated materials—raw data—inform our knowledge of the site and its relationship to other sites. After collecting 20 buckets of pottery from a fill layer, you may be tempted to think that all data isn’t important, but it is! What you find—and sometimes what you don’t find—reveals a lot about the site’s inhabitants. By excavating, you physically uncover the past and add new voices to a rich historical narrative.

025

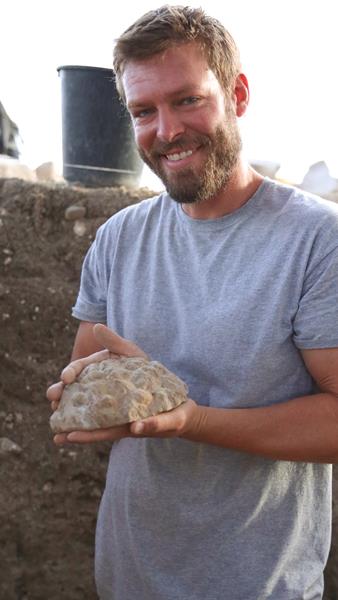

This past summer, I had the privilege of excavating at Tel Shimron in northern Israel. Our excavations uncovered a wealth of archaeological material. Plus, thanks to its position on the edge of the Jezreel Valley, one of the major thoroughfares of ancient Israel, Tel Shimron served as the ideal launching pad for me to visit several excavations in the biblical world.

Join me on a quick journey through northern Israel, as we explore eight incredible archaeological investigations furthering our understanding of the ancient world and biblical narrative.

026

«Stop 1» Tel Shimron

LOCATION: Jezreel Valley

PERIODS: Neolithic period (8300–5500 B.C.E.), Early Bronze Age (3700–2500 B.C.E.), Middle Bronze Age (2000–1550 B.C.E.), Late Bronze Age (1550–1200 B.C.E.), Iron Age I (1200–1000 B.C.E.), Iron Age II (1000–586 B.C.E.), Persian period (539–332 B.C.E.), Hellenistic period (332–37 B.C.E.), Roman period (37 B.C.E.–324 C.E.), Byzantine period (324–636 C.E.), Islamic period (636–1500 C.E.)

DIRECTORS: Daniel Master (Wheaton College) & Mario Martin (Tel Aviv University)

Located in the Jezreel Valley, Tel Shimron was occupied for more than eight millennia. During the Bronze Age, the site became a large Canaanite city with impressive fortifications. In fact, Tel Shimron was the largest city in the Jezreel Valley during the Middle Bronze Age (2000–1550 B.C.E.). People lived there on a smaller scale during the Iron Age and later periods. It was an agricultural settlement connected to Akko in the Hellenistic period (332–140 B.C.E.) before the area was taken over by the Maccabees. In the Roman period, it was a small Jewish village between Beth She‘arim and Sepphoris (first–fourth centuries C.E.), and it continued as an agricultural outpost through the Islamic period (636–1500 C.E.).

References to Shimron appear in the Hebrew Bible (Joshua 11:1; Joshua 12:20; Joshua 19:15), in027 Egyptian sources from the second millennium B.C.E. (specifically, texts from the 19th–18th, 15th, and 14th centuries), in the first-century C.E. autobiography of the Jewish historian Josephus (Life 115), and in the fourth-century Jerusalem Talmud.

The 2019 excavation season yielded remains from a variety of periods, including a coin hoard from the reign of the Seleucid king Antiochus III (223–187 B.C.E.), a faience wedjat (Eye of Horus) amulet from the Hellenistic period, fragments of electrum foil and a bronze bracelet from the 11th century B.C.E., and intact Middle Bronze Age vessels. In 2020, the team plans to excavate the Middle Bronze Age acropolis, Bronze Age domestic structures, Iron Age city, Hellenistic villas, and Roman houses.

028

«Stop 2» Legio

LOCATION: Jezreel Valley

PERIODS: Roman period (100–300 C.E.)

DIRECTORS: Matthew J. Adams (Albright Institute of Archaeological Research), Yotam Tepper (Israel Antiquities Authority) & Susan Cohen (Montana State University)

Across the Jezreel Valley from Tel Shimron, the site of Legio sits at the foot of Tel Megiddo (Armageddon). Occupied by none other than the Roman Sixth Legion (Legio VI Ferrata), it served as a Roman army base from the second–third centuries C.E. While the Sixth Legion controlled the Galilee in the province of Syria-Palaestina, the other imperial legion in the region—the Tenth Legion (Legio X Fretensis)—was stationed in Jerusalem.

Legio is the only full-scale second-century C.E. Roman base to be excavated in the Eastern Mediterranean. A Jewish and early Christian village, Kefar Othnai, was also discovered adjacent to and contemporary with the base.

The prize find from 2019 was the base’s sacellum, the holy room at the back of the principia, where the legion’s standards would have been stored. For those stationed at Legio, the sacellum would have been the most sacred spot in the camp, which is reflected in the room’s unique architecture. In 2021, the Legio team will continue uncovering this room and explore other portions of the main headquarters building.

029

«Stop 3» Shikhin

LOCATION: Lower Galilee

PERIODS: Late Hellenistic period (152–37 B.C.E.), Roman period (37 B.C.E.–363 C.E.)

DIRECTORS: James R. Strange (Samford University), Mordechai Aviam (Kinneret College on the Sea of Galilee) & Tom McCollough (Centre College emeritus/Coastal Carolina University)

Nestled on a hilltop in Galilee, the Jewish village of Shikhin served as a pottery production center and had close connections with its large, cosmopolitan neighbor Sepphoris. It was first settled at the end of the Persian period and grew throughout the Hellenistic period. According to Josephus, the site already had a substantial Jewish population in 103 B.C.E.—when Ptolemy Lathyrus took 10,000 of its residents captive (Jewish Antiquities 13.337; Jewish War 1.86). Although Josephus calls the site Asochis in the first century C.E., the second-century Tosefta and later rabbinic writings refer to it as Shikhin. These sources indicate that some wealthy Jewish families called the site home until it was abandoned in the fourth century C.E.

In 2019, the crew of the Shikhin Excavation Project recovered the first complete lamp mold at the site. Decorated with grapevines, grape leaves, and bunches of grapes, with an amphora or vase on its nozzle, the mold makes the top part of a Shikhin Decorated (Northern Darom) lamp and dates to c. 70–135 C.E. Nearby they found lamp fragments, another mold fragment, a small kiln, and pools probably used in the levigation of clay—all evidence of pottery production. Another “first” was the discovery of a stamped amphora handle dating to 167/165 B.C.E., with the inscription ’E[πɩ] ’Αρίστω/νος/Πανάμ[ο]ν, meaning “Under the oversight of Ariston, in the month of Panamos” (reading and dating by Donald Ariel of the Israel Antiquities Authority).

For the 2020 season, they will continue excavating the ancient village’s residential/industrial section, which produced both household ceramic wares and clay oil lamps for distribution in Galilee and probably Gaulinitis. Simultaneously, they will excavate the remains of the village’s large synagogue from the Roman period.

030

«Stop 4» Tell Keisan

LOCATION: Akko Coastal Plain

PERIODS: Early Bronze Age (3300–2000 B.C.E.), Middle Bronze Age (2000–1550 B.C.E.), Late Bronze Age (1550–1200 B.C.E.), Iron Age I (1200–950 B.C.E.), Iron Age II (950–586 B.C.E.), Persian period (539–332 B.C.E.), Hellenistic period (332–37 B.C.E.), Byzantine period (324–636 C.E.)

DIRECTORS: David Schloen (University of Chicago) & Gunnar Lehmann (Ben-Gurion University of the Negev)

On the boundary between Lower Galilee and the Akko Coastal Plain, between ancient Phoenicia and Israel, Tell Keisan sits on a hill overlooking trade routes. Throughout most of its existence, it had close ties to Akko. Although its ancient name is not known, excavators have uncovered a wealth of archaeological materials from the site, spanning some 6,000 years, from the Neolithic through Crusader periods.

Tell Keisan existed as a walled town during the Bronze and Iron Ages and frequently supplied its large neighbor Akko with food. Similar031 to Akko and most of northern Israel, it met its fate at the hands of the Assyrians in the eighth century B.C.E. Later, in the sixth century B.C.E., after a period of abandonment, Tell Keisan was reoccupied under the Achaemenid Persian rulers of the Levant. Smaller settlements continued at the site during the Hellenistic, Byzantine, and Crusader periods.

In 2019, archaeologists found an Iron Age room with a stone oil press in situ with pierced stone weights for the press lying nearby. The finds date to the eighth century B.C.E., before the Assyrian conquest. In 2020, the Keisan team will focus on publishing its finds, but they will return to excavate again in 2021.

032

«Stop 5» Tel Akko

LOCATION: Akko Coastal Plain

PERIODS: Middle Bronze Age (2000–1550 B.C.E.), Late Bronze Age (1550–1200 B.C.E.), Iron Age I (1200–1000 B.C.E.), Iron Age II (1000–586 B.C.E.), Persian period (539–332 B.C.E.), Hellenistic period (332–37 B.C.E.)

DIRECTORS: Ann E. Killebrew (Penn State University) & Michal Artzy (University of Haifa)

Positioned on the Mediterranean Sea and on two major land trade routes, the coastal city of Akko functioned as a trade center throughout its long history. At various times, Canaanites, Sea Peoples, and Phoenicians all called it home. People lived at the site from the Early Bronze Age through the Hellenistic period. Then the city moved west toward the bay, where the current “old city” is located, and came to be known as Acre.

Akko is well attested in historic documents, including second-millennium B.C.E. sources from ancient Egypt (18th–13th centuries B.C.E), Ugarit (13th–12th centuries B.C.E.), and Aphek (13th century B.C.E.), as well as first-millennium B.C.E. texts from Assyria and Greece. The city also appears in the Bible (Judges 1:31).

The most significant find from Tel Akko’s 2019 season is a Phoenician inscription found in a large pit (late seventh–early sixth century B.C.E.), together with nearly 400 buckets of pottery and numerous figurines. With less than half the pit excavated, there is still more to be recovered!

In 2020, the Tel Akko team will continue to excavate the site’s late Iron Age levels, reaching the Phoenician cities conquered and destroyed by the Neo-Assyrian kings Sennacherib (701 B.C.E.) and Ashurbanipal (644 B.C.E.). Additionally, the team will dig areas dating to the transitional Late Bronze/Iron I period (1300–1200 B.C.E.), where earlier excavations revealed an impressive industrial zone with installations that produced pottery, bronze artifacts, and the famous purple dye of the Phoenician coast.

«Stop 6» Tel Kabri

LOCATION: Western Galilee

PERIODS: Neolithic period (8300–4500 B.C.E.), Chalcolithic period (4500–3300 B.C.E.), Early Bronze Age (3300–2000 B.C.E.), Middle Bronze Age (2000–1550 B.C.E.), Late Bronze Age (1550–1200 B.C.E.), Iron Age I (1200–1000 B.C.E.), Iron Age II (1000–586 B.C.E.), Byzantine period (324–636 C.E.), Ottoman period (1500–1917 C.E.)

DIRECTORS: Eric Cline (George Washington University) & Assaf Yasur-Landau (Haifa University)

034

Boasting remains from the Neolithic through Ottoman periods, the mound of Tel Kabri reached its zenith from c. 1900–1700 B.C.E., during the Middle Bronze Age. Archaeologists have uncovered ramparts and an extensive Canaanite palace from that period, replete with floor and wall paintings and a large wine cellar. In addition to being one of the largest Middle Bronze Age sites in the southern Levant, Tel Kabri had connections to the035 Mediterranean world, evidenced by its Aegean-style paintings.

During the last days of the 2019 season, the Tel Kabri team found a new painted plaster floor in the Canaanite palace. This brings to mind the unwritten axiom that every archaeologist knows: The best things are always found on the last day(s) of the dig! During the next season (2021), the team hopes to excavate and expose enough of the floor to make sense of its design and influences—whether they were Aegean, Egyptian, Mesopotamian, or strictly local influences, for all are possibilities.

036

«Stop 7» Tel Hazor

LOCATION: Upper Galilee

PERIODS: Early Bronze Age (3000–2000 B.C.E.), Middle Bronze Age (2000–1550 B.C.E.), Late Bronze Age (1550–1200 B.C.E.), Iron Age I (1200–1000 B.C.E.), Iron Age II (1000–586 B.C.E.)

DIRECTORS: Amnon Ben-Tor & Shlomit Bechar (Hebrew University of Jerusalem)

The largest site in the southern Levant, Hazor never fails to impress. Occupied through the Bronze and Iron Ages (c. 2800–732 B.C.E.), it was a major Canaanite and, later, Israelite city. Hazor appears in multiple biblical passages (Joshua 11–12; Judges 4; 1 Samuel 12:9; 1 Kings 9:15; 2 Kings 15:29), which describe the city’s destruction by the Israelites, rebuilding by King Solomon, and later defeat by the Assyrian king Tiglath-pileser III in 732 B.C.E. Archaeological discoveries have challenged elements of this narrative, but there is no doubt that Hazor was a powerful city, truly the “head of all those037 kingdoms” (Joshua 11:10). The site also appears in second-millennium B.C.E. texts from Egypt (18th–13th centuries B.C.E.) and Mari (18th century B.C.E.), the second-century B.C.E. Book of 1 Maccabees (11:67), and Josephus’s first-century C.E. writings (Jewish Antiquities 5.199).

The year 2019 marked the 30th season of the renewed excavations at Tel Hazor. The team’s excavations focused on the eighth-century B.C.E. city, which was destroyed by Tiglath-pileser III. They exposed part of this destruction level—with many broken and intact pottery vessels. Other prize finds included a decorated stone spoon, bronze bracelet, figurine fragment, and bronze fibula. They also conserved a pristinely preserved staircase, which was uncovered in 2018. It leads to the west, toward what they believe is the main entrance of the administrative palace. So far, the staircase comprises seven basalt slabs, each measuring about 15 feet long and cut precisely for use as a step.

In 2020, they will continue excavating the eighth-century city. By the end of the season, they hope to reach the destruction level of the southern halls of the Late Bronze Age administrative palace.

038

«Stop 8» Abel Beth Maacah

LOCATION: Upper Galilee

PERIODS: Early Bronze Age (3000–2000 B.C.E.), Middle Bronze Age (2000–1550 B.C.E.), Late Bronze Age (1550–1200 B.C.E.), Iron Age I (1200–980 B.C.E.), Iron Age II (980–586 B.C.E.), Persian period (539–332 B.C.E.), Hellenistic period (332–37 B.C.E.), Byzantine period (324–636 C.E.), Late Islamic period (1291–1517 C.E.), Ottoman period (1517–1917 C.E.)

DIRECTORS: Robert Mullins (Azusa Pacific University), Nava Panitz-Cohen & Naama Yahalom-Mack (Hebrew University of Jerusalem)

Our tour ends in the far north of Israel with Abel Beth Maacah, a city at the meeting point of ancient Israel, Phoenicia, and Aram. Mentioned in biblical (2 Samuel 20; 1 Kings 15; 2 Kings 15), Egyptian (18th- and 15th-century B.C.E.), and Assyrian (eighth-century B.C.E.) texts, Abel Beth Maacah was probably an Aramean city, which may have fallen under Israelite control during the Iron Age. Founded in the Early Bronze Age (c. 3000 B.C.E.), the site was occupied until the Iron Age II—when Tiglath-pileser III conquered it in 732 B.C.E.—and then on a smaller scale during the Persian and later periods.

The 2019 season had many developments and surprises, particularly related to the Iron Age. In addition to revealing an Iron Age I (1200–980 B.C.E.) occupation, archaeologists unearthed—from the same period—a basalt stone mortar that flanked a (previously excavated) plastered installation topped by two basins, uncovered from a cultic context,a and a small ivory seal with a carved face on the back and a tree039 flanked by an ibex and ostrich on the front. From Iron IIA (980–840 B.C.E.) contexts, they discovered a bridled horse head that would have sat on a kernos (a pottery ring with several smaller vessels or figurines attached to it), a “little drummer girl” figurine with the paint still preserved on the drum, and a seal impression bearing a “Lord of the Animals” motif on a storage jar sherd,b as well as a room of storage jars, one with an ink inscription.

They also found a beautifully painted juglet and a scarab from the Middle Bronze Age II (1750–1650 B.C.E.).

These new discoveries shed light on the rise of Israel and other emerging tribal entities spanning the period of the Judges through the Omride Dynasty and up to the reign of Jeroboam II. In 2020, the Abel Beth Maacah team plans to expand all of the areas from the Iron Age I–IIA to better capture what life must have been like in this border town.

Starting in the Jezreel Valley and traveling to Upper Galilee, explore eight excavations in northern Israel. These digs are literally uncovering the ancient world and rewriting history.

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Footnotes

1. Nava Panitz-Cohen and Naama Yahalom-Mack, “The Wise Woman of Abel Beth Maacah,” BAR, July/August/September/October 2019.

2. This is identical to an impression found on one of the snake pithoi at Tel Dan. See Avraham Biran, “Sacred Spaces,” BAR, September/October 1998.