Fragments of Luxury: The Jerusalem Ivories

The ivories from the Givati Parking Lot excavation are some of the most unique and valuable artifacts to have been unearthed in Jerusalem in recent years. This is the first time such high-value items—otherwise known only from ancient royal capitals like Nimrud and Samaria—have been found in Jerusalem. Discovered within the ruins of Building 100, which is the largest Iron Age public building ever found in the city (see “Rich & Famous”), the fragments originally came from small plaques attached to wooden objects, most likely pieces of luxury furniture that adorned the upper floor of the building.

Here, I examine the decoration and symbolism of these ivory pieces, their possible origin, and what they reveal about the lives of ancient Jerusalem’s wealthiest residents.

During the excavation, nearly 1,500 ivory pieces were collected, many having been heavily burnt during the destruction of the building, presumably in 586 BCE. After restoration, it became clear that despite the many fragments, the pieces were from just a handful of decorative ivory plaques. The backs of the plaques are smooth but have thin incisions that were used to affix them to furniture and other objects using glue. Nails or pins may have also been used, as some plaques have tiny holes in their corners.

The restored ivory plaques show three different types of decoration. The first, reconstructed on two square plaques, features a frame of 12 rosettes surrounding a stylized depiction of a date palm. Parts of the design were painted in red, white, and gray to create contrast. A well-known royal symbol throughout the ancient Near East, the rosette motif adorned the clothes, objects, and reliefs of Assyria’s imperial rulers. During the Iron Age, local Levantine rulers also adopted the rosette as a royal symbol, probably under Assyrian influence. In Judah, the rosette became the official symbol of the royal administration, and it appears frequently on stamped jar handles.a Similarly, the “tree of life”—often depicted as a stylized date palm—was a common artistic motif that represented fertility, prosperity, and divine protection. In Judah, palmette volutes decorated the stone capitals of royal and administrative buildings throughout the kingdom, including Building 100 in Jerusalem and the palatial structure at Ramat Rahel.

A different floral design appears on two rectangular plaques. These pieces depict a series of interconnected budding lotus flowers. The flowers are a darker brown, while the background is a lighter yellow, which again creates a striking color contrast. The lotus flower, originally from Egypt, was one of the region’s earliest artistic motifs. It symbolized creation and renewal, and it was frequently associated with kings and royalty. The repeating image of lotus flowers likely represents an endless cycle of life.

A third, geometric design was identified on a single rectangular plaque. The design, which appears as a series of diamond-like shapes punctuated by circles, was carved in broad lines into a blackened piece of ivory, which allowed the ivory’s original color to stand out. An almost identical plaque was found at Nimrud. Such geometric designs, which incorporated different patterns of diagonal lines, circles, and triangles, were used to fill space, especially on smaller plaques where there was little room for larger or more detailed figures.

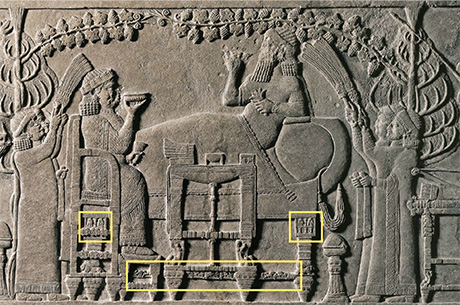

The Jerusalem ivories are similar to those found at other royal capitals of the Iron Age, including Nimrud, the capital of Assyria, and Samaria, the capital of the Northern Kingdom of Israel. In the ancient Near East, small ivory plaques often decorated wooden furniture, boxes, and other crafted luxury items that typically belonged to royalty and wealthy elites. But since wooden objects rarely survive in the archaeological record, our main evidence for how the ivories looked when adorning such pieces is ancient pictorial art, especially royal reliefs. The famous Garden Scene relief from Nineveh, for example, portrays King Ashurbanipal (r. 669–631 BCE) lying on a bed while his queen, Libbali-sharrat, sits on a chair before him. The furniture seen in the relief is decorated with inlaid ivory plaques, including pieces that depict two female figures looking out from a balustraded window or balcony.b

The ivories from Nimrud appear to have originated in the Levant and were likely received as tribute or taken as loot during Assyrian military campaigns. Unfortunately, the Samaria ivories were found in later Hellenistic-period fills, so it is impossible to know where they originated. Given their large number and quality, however, some scholars believe they were made locally during the last years of the Northern Kingdom, when Samaria reached considerable wealth and influence.

So where were the Jerusalem ivories made, and how might they have ended up in Building 100? There are two possibilities for how the ivories arrived in Jerusalem. First, they could have been imported from outside Judah, either as individual decorative panels or as luxury furniture items that already had the pieces attached. The royal official who operated from Building 100 may have acquired the pieces through the long-distance trade networks that flourished under the Assyrian Empire. Alternatively, they may have been gifts from the Assyrian rulers, who commonly gave such precious objects to local kings and officials to ensure their loyalty.

Second, the ivories may have been produced locally, perhaps even in Jerusalem. After all, precious objects carved from wood and bone have been found in other Jerusalem excavations, and the craftsmen who made such pieces were usually highly mobile, sometimes traveling from distant regions to practice their craft with a simple, compact set of tools. In either case, the newly discovered ivories demonstrate that Jerusalem’s wealthiest residents were able to obtain luxury goods, whether through trade, gift exchange, or access to skilled artisans.

More than anything, the ivory plaques from Building 100 show that Jerusalem was well connected to the wider region during the late Iron Age. Its wealthiest residents were well versed in the fashions of the day and benefited from the trade and movement of high-end luxury goods, materials, and craftsmen that were supported through the Assyrian Empire.

MLA Citation

Footnotes

1. See Oded Lipschits, “Enduring Impressions: The Stamped Jars of Judah,” BAR, Winter 2022.

2. Similar ivories are well known in the archaeological record. See Lacy K. Crocker Papadakis, “Understanding the Woman in the Window,” BAR, Winter 2023.