Some two dozen fragments of Egyptian statues have turned up in the excavations of the Canaanite city of Hazor. This is one of the largest troves of Egyptian statuary from anywhere in the ancient Levant, yet most of the statues were found in archaeological contexts that date centuries after the pieces were first made. How did this happen, and why were all these statues eventually destroyed?1

The site of Hazor, in the Upper Galilee about 10 miles north of the Sea of Galilee, is the largest archaeological mound in Israel. At its height during the Middle and Late Bronze Ages (c. 1800–1200 BCE), the city included both an Upper and Lower City that extended across an area of nearly 200 acres, rivaling the size of such powerful Syrian city-states as Mari, Ebla, and Qatna. Given its prominence during the time of the Canaanites, the biblical writers famously remembered Hazor as the “head of all those kingdoms” prior to the Israelite conquest (Joshua 11:10).

Hazor has been excavated by Hebrew University’s Institute of Archaeology since 1955, first under Yigael Yadin in the 1950s and 1960s and then by Amnon Ben-Tor in the 1990s. Today, archaeological work at the site continues under my direction as part of the Selz Foundation Excavations.

The focus of our current excavations is Area M, where the ancient roadway leading from Hazor’s Lower City enters into the Upper City, or acropolis. In recent years, a sizable number of Egyptian statue fragments have come to light in this area. These artifacts are easily identified by their high level of craftsmanship and use of non-local stone. In 2022, the reason we have so many statue fragments from this area finally became apparent, as excavations exposed the entrance to the city’s Late Bronze Age administrative palace, where the king of Hazor and his family lived. The entrance features a basalt staircase along with two rounded basalt pillar bases that fit perfectly into the upper stairs. Such monumental entrances are typical of Bronze Age palaces, such as the ones uncovered at Alalakh and Ugarit.

In addition to the ten statue fragments found in Area M, another 14 fragments were found near the center of the site in Area A, which features a massive ceremonial precinct. With these two dozen fragments (that belong to 22 or 23 separate statues), Hazor has produced the largest amount of Egyptian statuary in the Levant except for Byblos, a prominent port city on the Lebanese coast that was in nearly continuous contact with Egypt across several millennia. This fact is somewhat surprising, especially considering Hazor was never an Egyptian stronghold, nor was it located in the southernmost part of Canaan, an area that was routinely under Egyptian influence.

Nearly all the statue fragments were discovered in Late Bronze Age deposits and show no signs of having been local imitations. They depict either Egyptian kings or high officials and some carry hieroglyphic inscriptions. Made of Egyptian stones, they display the high quality of workmanship typical of Egyptian sculptures. All show signs of deliberate mutilation, most likely caused by those responsible for the city’s destruction in the late 13th century BCE (see sidebar, “From Venerated to Mutilated”).a

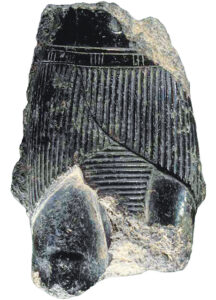

Among the most notable statue fragments is a piece that shows the front paws of an Egyptian sphinx flanking an engraved hieroglyphic inscription bearing the name of the Old Kingdom king Menkaure, builder of one of the great pyramids in Giza. The statue is made of gneiss, a valuable and very hard, dark stone.

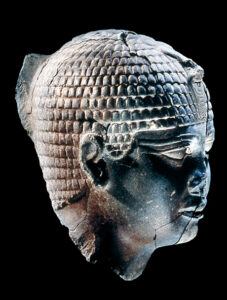

Another prominent example is the head from a small statue of an Egyptian king made from graywacke, a stone quarried only in Wadi Hammamat in Egypt. The figure is portrayed wearing a short, close-fitting headdress, topped by a uraeus, which clearly identifies him as a king. While it is impossible to identify the depicted king, the stylistic features—especially the oval-shaped face and fleshy cheeks—point to an Old Kingdom ruler, most likely one from Egypt’s Fifth Dynasty.

A third example is a fragment from the lower part of a life-size statue of a squatting figure. Even though most of the statue is missing, the hieroglyphic inscriptions preserved on the base identify it as a representation of Nebipu, a high priest who served in the temple of the god Ptah at Memphis during the reign of Amenemhat III, a pharaoh of Egypt’s 12th Dynasty during the Middle Kingdom.

Strangely, the above examples and nearly all of the other Egyptian statue fragments found at Hazor were manufactured centuries earlier than the contexts in which they were found. Two fragments (the front paws of Menkaure’s sphinx and the head of the Egyptian king) are from the early Old Kingdom (26th–25th centuries BCE), while the remaining fragments date from the Middle Kingdom (20th–18th centuries BCE). How did these already ancient statues find their way into the destruction debris from the final phase of Late Bronze Age Hazor in the 13th century BCE?

One possibility is that the statues were brought to Hazor shortly after their production—namely during the Old and Middle Kingdoms—and retained their importance for many generations, surviving the city’s many changes, in some cases, for more than a millennium. Theoretically, this argument bears merit, as we know that ancient Near Eastern ideology tended to glorify the past, seeing ancient rulers as greater and stronger than those of the present. Therefore, it was common for royal statues to remain in use for generations. One such example among the fascinating finds from Hazor’s ceremonial precinct is a locally produced bronze statue of a Canaanite king. Although the statue was found in a Late Bronze Age context, its style and features suggest it was made during the Middle Bronze Age and, therefore, must have been continuously displayed for more than four centuries.2

This, however, does not seem to be the case with the Egyptian statues from Hazor. In general, there is minimal evidence for contact between Egypt and Hazor during the Old and Middle Kingdoms. Indeed, if the statues were imported to Hazor during these earlier periods, we would expect to find at least some fragmentary or even complete statues in the corresponding Early and Middle Bronze Age levels at the site, but we do not. Furthermore, the inscriptions on some of the statues disclose their original association with Egyptian funerary and temple cults, clearly indicating that their use at Hazor was secondary and unrelated to their original function.

A second possibility is that the statues were sent to Hazor centuries after they were made. This possibility seems to accord better with the Late Bronze Age context in which most were found. But when did this happen and under what circumstances? Throughout Egyptian history, royal statues were often reused and repurposed, and many such statues have been discovered in later archaeological contexts at various sites in Egypt, as well as in Nubia and the Levant. One historical period in which this phenomenon was particularly common was the Second Intermediate Period (18th–16th centuries BCE), when Lower Egypt was ruled by the Hyksos, kings of Levantine origin who ruled from their capital at Avaris (Tell el-Daba) in the Nile Delta.3 Therefore, many of the Middle Kingdom statues may have arrived in Hazor during the Hyksos period. Inscriptions on three of the statues indicate they originated from the area of Memphis, while the inscription on the sphinx of Menkaure suggests it came from Heliopolis. Both places fell within the realm of the Hyksos.

Archaeological evidence indicates close commercial and cultural relations between Egypt and the southern Levant during the time of the Hyksos. The Hyksos’s Canaanite origins could account for their interest in sending royal statues to their brethren in the Levant. Yet Egyptian imports into the southern Levant during the Hyksos period were limited almost exclusively to scarab seals. Furthermore, although the Hyksos Dynasty (15th Dynasty) is roughly correlated with the very end of the Middle Bronze Age in the Levant, at Hazor, not a single statue fragment can be associated with strata contemporary with the rule of the Hyksos.

Widespread reuse of Middle Kingdom royal statues was also common during the Ramesside period (late 19th and 20th Dynasties)—corresponding to the Late Bronze Age in the southern Levant—when such statuary was brought from Memphis and Avaris to Piramesse, the capital city built in the eastern Nile Delta by Ramesses II.4 The number of Middle Kingdom statues reworked in the Ramesside period reflects the popularity of this practice at the time. The apparent looting of Middle Kingdom monuments—mostly from the ancient capital city of Memphis, the Fayyum Oasis, and the Hyksos capital at Avaris—may account for the appearance of at least some Middle Kingdom statues in the Late Bronze Age southern Levant, including at Hazor. Indeed, most of the other Egyptian finds from Hazor come from the Late Bronze Age. They include pottery, alabaster vessels, and a recently discovered silver ring of the 18th Dynasty pharaoh Smenkhkare (r. 1336–1334 BCE). One of the most outstanding finds from the Ramesside period is a part of an offering table bearing the name Prahotep, who was a vizier and high priest during the reign of Ramesses II. These unique items and many others attest to the strong ties between Hazor and Egypt during the New Kingdom.

But why were these statues sent to Hazor? During the Late Bronze Age, the southern Levant was under Egyptian hegemony.b The region’s cities paid taxes to Egypt and supported Egyptian troops during their northern campaigns, while the New Kingdom pharaohs resolved (but also stoked) disputes between their Canaanite vassals, employing military might when needed. We also know of several Egyptian strongholds, such as Beth Shean in the Jordan Valley and Jaffa along the Mediterranean coast, where Egyptian garrisons and officials resided.

Considering Egypt’s control over the area, one may speculate that the Egyptian statues were brought to Hazor by the Egyptians themselves, as powerful symbols of their domination over the region. Alternatively, the statues could have been procured by Hazor’s Canaanite rulers to demonstrate their allegiance to Egypt. Every Egyptian official who visited would immediately see Egyptian statues placed at prominent positions within the city’s palaces and temples. But if either scenario were the case, the imperial officials or local rulers would more likely display statues of the contemporary Egyptian pharaohs who were owed allegiance, not those of dynasties long gone.

It seems, therefore, that the key to understanding the Hazor Egyptian statues is their artistic quality rather than the identity of the kings or officials they depicted. The technical expertise of Egyptian sculptures exceeded the abilities of local Canaanite craftsmen. Egyptian statues were made with high-quality Egyptian stone that did not exist in the Levant. It is possible that Canaanite rulers, and particularly the kings of Hazor, saw Egyptian statues as the apex of artistic craftsmanship of their time. Such statues would then have been prestige or collector’s items, presenting the wealth and power of their new owners. In such a case, the statues were appreciated more for their style than for being images of long-deceased rulers. Perhaps equally important, such statues were probably easier to acquire through trade than objects of contemporary Egyptian art.

The question remains whether the statues found at Hazor were sent directly by the Egyptian court as diplomatic gifts or were imported into the city by Egyptian envoys or merchants traveling through the southern Levant at the time. Unfortunately, we simply don’t yet have enough evidence to make that determination, though the former scenario seems more likely given Hazor’s size and importance during the Late Bronze Age. Indeed, in the well-known Amarna Letters from the 14th century BCE, the ruler of Hazor is the only Canaanite vassal who refers to himself (and is known to others) as “king.” This title was usually reserved for the rulers of the period’s great powers, including the Hittites and the Babylonians, while the rulers of vassal kingdoms were simply called “governors.” This suggests that Hazor enjoyed an elevated status relative to other Canaanite city-states.

As we move our excavations into the Late Bronze Age administrative palace during the forthcoming seasons, more Egyptian statues might come to light, giving us more clues as to how and why these high-end artifacts ended up at Late Bronze Age Hazor.

MLA Citation

Footnotes

1. Amnon Ben-Tor, “Who Destroyed Canaanite Hazor?” BAR, July/August 2013.

2. Carolyn R. Higginbotham, “The Egyptianizing of Canaan,” BAR, May/ June 1998.

Endnotes

1. I thank Daphna Ben-Tor for insightful discussion on the topic of this article and for her comments on an early draft.

2. Tallay Ornan, “The Long Life of a Dead King: A Bronze Statue from Hazor in Its Ancient Near Eastern Context,” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 366 (2012), pp. 1–24.

3. Alexander Ahrens, “Remarks on the Dispatch of Egyptian Middle Kingdom Objects to the Levant During the Second Intermediate Period,” Göttinger Miszellen 250 (2016), pp. 21–24.

4. Marsha Hill, “Later Life of Middle Kingdom Monuments: Interrogating Tanis,” in A. Oppenheim et al., eds., Ancient Egypt Transformed: The Middle Kingdom (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2015), pp. 294–299.