036

037

Plunderers, probably in ancient times, looted the Akeldama tombs described in the previous article. Not a single artifact remained when archaeologists entered those tombs: Only the chambers themselves, with their decorative elements, survived.

In 1989, however, we discovered three cave tombs in Akeldama that had lain undisturbed for nearly 1,500 years and were filled with grave goods.1 Why were these three burial caves not emptied of their contents long ago? The answer is simple: No one knew they existed.

As has often happened in Jerusalem when a road is being built, the phone rang at the Antiquities Authority. The municipality was widening a road in Abu Tor leading to the village of Silwan. We were aware that work was being done in the Akeldama area, so it came as no surprise to learn that bulldozers had uncovered a number of square openings hewn into the rock. At that point all construction stopped and the archaeologists were called in. Upon arriving at the scene, we crawled through the small openings: They led to a large burial complex that was, amazingly, still intact. Inside, our flashlights revealed an abundance of artifacts scattered on the floor—pottery, glass vessels, jewelry, oil lamps, even ossuaries (bone boxes)—indicating the caves had escaped plunderers in ancient and modern times.

Both the architecture of the cave complex and the finds indicated 038clearly that these tombs were originally used in the first century C.E., terminating in the year 70 C.E. when Jerusalem was conquered and destroyed by Roman legions. One of the coins we later found was from the second year of the First Jewish Revolt against Rome—that is, 67 C.E.

Alongside the rich finds from the original burial phase at the end of the Second Temple period, we also recovered solid evidence that the tombs were used by Romans during the Late Roman period (second to fourth centuries C.E.) and by Christians during the Early Byzantine period (fifth and sixth centuries C.E.). From the latter period, we found numerous clay oil lamps decorated with crosses.

In their original phase, these tombs were unmistakably part of an elegant, ornate Jewish cemetery. This supports Leen and Kathleen Ritmeyer’s conclusion that Akeldama could not have been the “potter’s field” referred to in the New Testament as the “Field of Blood” (Matthew 27:7–8). On the contrary, these tombs could only have been built by affluent families capable of affording luxurious burial chambers. In the second phase (the Late Roman period), these caves were used to bury pagan Romans who practiced cremation. In the final phase (the Early Byzantine period), they were probably used by monks for burials, perhaps in the mistaken belief that this was the Potter’s Field where strangers were buried.

What is extraordinary and almost incomprehensible is that the later users did not plunder or remove materials from earlier burials, except to the extent necessary to accommodate their own burials. Were they trying to preserve evidence for 20th-century archaeologists by leaving behind artifacts allowing us to reconstruct 600 years of burial customs in Jerusalem? If so, they did a good job.

Once the bulldozer uncovered the openings, we organized an excavation to begin the next day. Our task was complicated by security problems. The caves lie in an area where, in 1989, the intifada was in full swing: The Arab villages east of Jerusalem experienced numerous incidents of stone-throwing and tire-burning. We were able to separate our excavations from the surrounding violence, however, by employing Arab workers from Silwan and carefully explaining our work to the local people who gathered to watch for hours on end, standing outside the caves.

After we found a number of gold rings and earrings, we read about it two days later in the East Jerusalem newspaper Al Kuds, which described “vessels loaded with gold” brought out of the caves. This exaggerated story was worrisome, for it might easily have attracted 039antiquities robbers. We decided to station armed guards at the site after work hours and throughout the night.

When the excavation was completed, the cave entrances were closed and blocked with mounds of earth to prevent unauthorized entry. (The path of the new road was also changed so as to bypass the caves.)

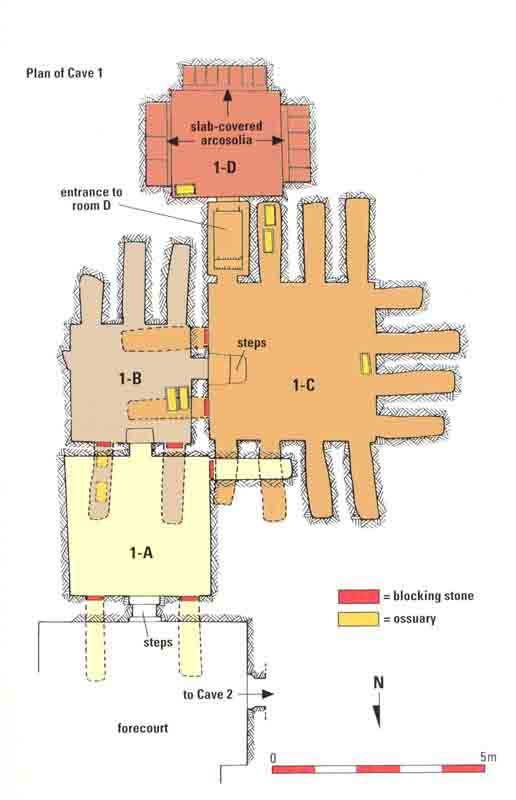

We numbered the three burial caves 1, 2 and 3, and assigned letters to each of their chambers. Certain features were common to all three caves. All were entered from a forecourt, with Caves 1 and 2 sharing the same forecourt. Their walls were meticulously hewn in the hard limestone and given a fine aesthetic finish; carefully and precisely cut right angles join the walls with the floors and ceilings.

Each of the caves also contained loculi, ossuaries and arcosolia, all typical of Jewish burials in the Second Temple period. A loculus (kokh and kokhim [plural] in Hebrew) is an elongated cavity cut into the rock, perpendicular to its face, to hold the body of the deceased in the initial burial. Some loculi were also used as repositories for ossuaries. The typical loculus is about 6 feet deep, 1.5–2 feet wide and 2 feet high.

It was customary among Jews in Jerusalem during the latter part of the Second Temple period to re-bury the deceased about a year after the initial burial. In this secondary burial, the bones were placed in a smallish box called an ossuary.2 Almost all of the thousands of ossuaries that have been recovered are made of limestone. The typical ossuary is about 1.5–2.5 feet long (long enough to hold the largest bones), 1 foot wide and 1.5 feet high. Some ossuaries have four small pedestals, and many are inscribed in Hebrew, Aramaic or Greek, generally with the name of the deceased.

An arcosolium is another type of receptacle carved into the wall where the deceased’s body was initially laid. It is a wide, arched opening, sometimes with a trough at the bottom, into which the body was placed parallel to the wall.

Cave 1 was especially rich in loculi and arcosolia. From the forecourt, three rock-carved steps lead to a precisely carved square room (1-A) that had served as the entrance chamber to three additional square rooms (1-B, C and D). Room 1-B had five loculi cut into the walls. Room 1-C had 14 loculi—two flanking the entrance and four in each of the other three walls. However, one of the loculi had been widened to form a passageway with two rock cut steps leading down into room 1-D.

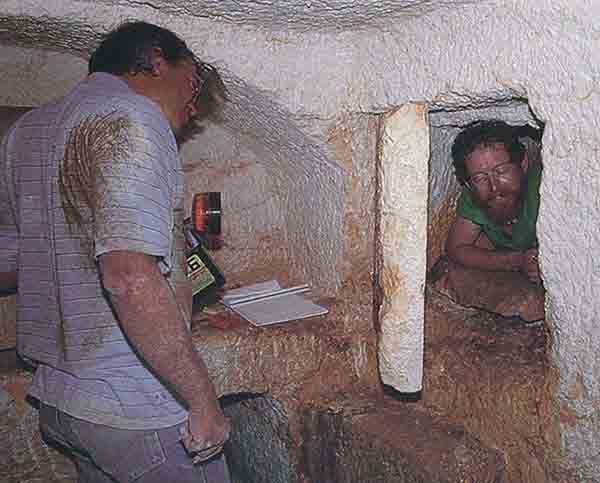

One of the loculi in room 1-A was still closed by its original blocking stone. Traces of plaster that once attached blocking stones to the chamber walls were also preserved around the openings of several other loculi.

In room 1-B, two ossuaries were found lying on the floor near the entrance to room 1-C, and two others were stored in a loculus. Two additional ossuaries were also found in a loculus in room 1-C.

040

Room 1-D contained three arcosolia, one on each wall. The arcosolia all had burial troughs, each of which was covered by several rectangular stone slabs adjoined with plaster to one another and to the walls of the trough.

Unlike the other rooms in this cave complex, the entrance chamber (room 1-A) was partially filled with silt and earth 1.5 to 2 feet deep. This accumulation on the chamber floor contained a rich deposit of finds representing the entire chronological range of the cave’s use from the Second Temple period through the Byzantine period. Since these finds were all mixed together, rather than stratified, it appears that the cave complex was at least partially cleared in antiquity and the deposits removed to the entrance chamber. The finds included glass vessels and clay oil lamps, as well as bowls and storage jars from all three burial periods. Some of the numerous Byzantine oil lamps were decorated with crosses, providing clear evidence that Christians were buried in this room.

In one corner of the entrance chamber, we found the remains of wooden coffins that were used in the Byzantine period. Beside them were several gold earrings probably dating to the Roman period, as well as glass vessels and oil lamps that should probably be ascribed to both the second and third phases of the tomb’s use, the Late Roman and Byzantine periods.

Although room 1-B had no accumulation of dirt or silt, numerous glass “candlestick” bottles with long narrow necks were scattered on the floor. These can be dated to the Late Roman period. In the corners of this room we also found piles of bones, most of them showing evidence of cremation.

Both the candlestick bottles and the charred bones point to a later phase of use—from the second to the fourth centuries C.E.—when Jerusalem’s Roman inhabitants practiced cremation. Cremation, of course, has always been prohibited by Jewish law. In the Late Roman period, furthermore, Jews were barred from Jerusalem, and even the city’s name was changed—to Aelia Capitolina—in order to obliterate any Jewish connection with the city. What is remarkable, however, is that the Romans who used this chamber for their own burials did not disturb the Jewish ossuaries lying on the floor, except to make use of them occasionally as receptacles for the remains of cremated Romans.

Additional evidence of cremation lay in the corners of room 1-C, where we found some charcoal, eliminating any doubt that the bodies had been cremated. Charred bones were also found in an ossuary in this room.

The only things lying in the troughs of the 041arcosolia in room 1-D were two glass vessels and a small green-glazed amphoriskos—a small amphora, usually used for holding liquids—of Parthian (Iranian) origin. These can all be dated to the first century C.E. Because the amphoriskos is of foreign origin, having no parallel in Second Temple Jewish burials, the person laid in the trough probably came from elsewhere and had a special status. It is puzzling that the amphoriskos and the two rare glass vessels (also without parallels in Jewish burials) were not removed from the trough when the deceased’s bones were collected and placed in an ossuary.

If it is reasonable to conclude that the Jewish family in Cave 1 came from outside Palestine, there is stronger evidence that Caves 2 and 3 also belonged to wealthy Jewish families from the Diaspora. We even know their names. Cave 2 belonged to the Eros family, obviously a deeply Hellenized family bearing a Greek name, and Cave 3 was the property of the Ariston family.

The Eros family tomb consisted of a primary room with ten loculi and an opening in the floor leading down to a lower level with two more rooms. One of these lower rooms (2-B) served as a repository for ossuaries, with 11 ossuaries found stacked one on top of another. The other room (2-C) contained additional loculi and three arcosolia. Access to the Eros family tomb was by way of the courtyard shared with Cave 1.

On the floor of the main room in the Eros family tomb we found four ossuaries and an accumulation of human bones nearly two feet deep mixed with fragments of wooden coffins. At the highest level of the accumulation were several skeletons lying side by side, some of which had been placed in wooden coffins. Clay oil lamps, coins and glass vessels from the Byzantine period were found near the skeletons. Apparently, this chamber had been used for burials initially in the late Second Temple period and was then re-used in the Byzantine period. The multiple burials, with bones literally in piles, suggest that this chamber might have served as a burial ground for monks who inhabited caves in the nearby Kidron Valley in the Byzantine period. Multiple burials have been found in several monasteries in the Judean desert and in Sinai, as well as in communal burial caves.3

We have called this cave the Eros family tomb because several of the ossuaries are inscribed with this name. Eros is a well-known Greek name, which appears for the first time in the Jewish onomasticona of the Second 042Temple period in Palestine. The family came from the north—perhaps somewhere in Syria or Lebanon—or at least had connections with northern Jews. One of the ossuaries identifies a woman named Eiras from the city of Seleucia. Two cities in Syria bore this name, one the port of Antioch, the other west of Apamea.

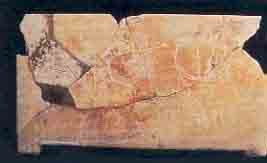

A most unusual ossuary, larger than the others, bears a fine, deeply incised inscription reading, “Eleazar of Beirut has made it.” On one of the long sides of the ossuary, the name of the deceased is inscribed, “Belonging to Eros.” But it is the name of the maker, Eleazar, that is featured—it appears above a fine schematic relief of a horned animal, probably a bull’s head, on one of the ossuary’s narrow sides. This is an extremely rare example of a figurative motif on a Jewish ossuary of the late Second Temple period. Almost all the decorations on the thousands of ossuaries recovered from this time are geometric, floral or architectural (that is, carrying motifs from buildings). In fact, we know of no other Jewish ossuary containing an animal or human figure. Archaeologists, of course, are always on the lookout for finds that don’t fit into any known pattern—and then the trouble begins. That is the case here, for the Second Temple period is known to have been strictly aniconic, keeping to a very narrow interpretation of the Second Commandment’s prohibition against graven images.b

The entrance to the farthest room in this cave (2-C) was sealed with a rectangular stone door on a pivoting hinged socket. An iron bolt secured the door 043by hooks affixed with lead to the stone. Stone doors pivoting on a hinge are found in only the most elaborate tombs of this period, such as the famous Tombs of the Kings (actually the tomb of Queen Helena) in east Jerusalem. The stone door in the Eros family tomb is unique, however, in that the locking device is still attached to it.

Just inside this third room was a rectangular stone stopper in the floor. Removal of the stopper revealed a small cell containing a single, but magnificent ossuary decorated in floral motifs in relief. The ossuary contained bones collected from one individual, carefully arranged and placed in it.

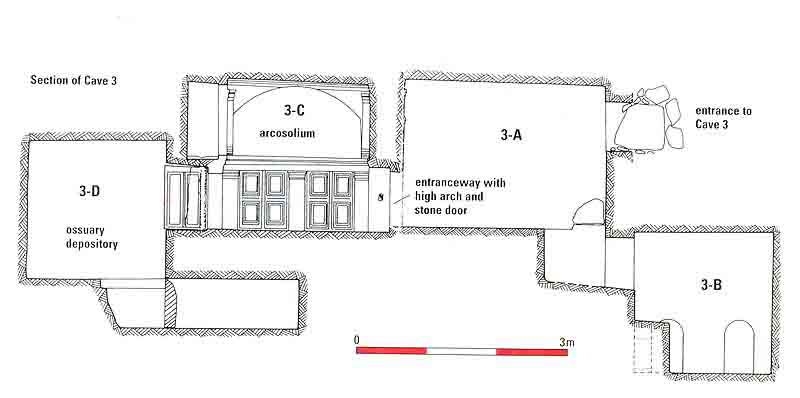

Cave 3, the Ariston family cave,c was in some ways the most affluent. The original entrance to this cave was blocked by silt, so we entered by a narrow breach between one of the rooms in Cave 1 (1-B) adjoining a room in Cave 3 (3-B). We found 25 ossuaries in the four rooms of Cave 3. About half of them bore Hebrew or Greek inscriptions. Most of the deceased whose names appear belonged to the Ariston family. One ossuary identifies its owner, probably the family patriarch, as “Ariston of Apamea.” Evidently, the family traveled from Apamea in Syria to Palestine during the first century C.E., settling in Jerusalem.

Possibly this Ariston of Apamea is the one 044mentioned in the Mishnah, the code of rabbinic law compiled in about 200 C.E., which forms the core of the Talmud. Tractate Hallah 4:11 states that “Ariston brought his first fruits from Apamea and they accepted them from him, for they said: He that owns (land) in Syria is as one that owns (land) in the outskirts of Jerusalem.”

If our Ariston of Apamea is indeed the wealthy Jew from Apamea who contributed to the Temple, this is one of very few instances in which persons known from ancient sources also appear in Jerusalem’s archaeological record. To date, only three such persons have been identified in ossuary inscriptions: Nicanor of Alexandria, who donated the gates to the Temple and whose name was inscribed on an ossuary in a burial cave on Mount Scopus; Theophilus the high priest, whose granddaughter’s ossuary was recently published; and Caiaphas the high priest, who was probably 045the owner of an ossuary recently found in the Jerusalem Forest.4

Cave 3’s four chambers are on several levels. Like the Eros family tomb, one room (3-D) was a depository for ossuaries, containing 11 ossuaries stacked one on top of another. In another room (3-B), one of the ossuaries contained cremated remains and glass candlestick-style bottles from the second and third centuries C.E.—evidence of secondary pagan use during the Late Roman period.

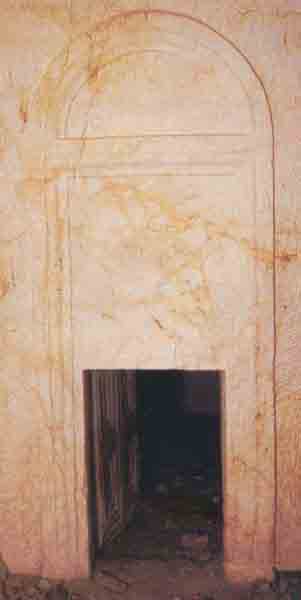

The most striking part of Cave 3, however, is room 3-C, an elegant chamber that is richly carved and decorated. The room is entered through a high doorway consisting of a very tall arch (two-and-a-half times as tall as the door itself) decoratively carved in low relief in the stone wall. The extraordinary heavy stone door at the bottom of the arch is still in place. It is carved with four panels in deep relief, two above and two below, apparently in imitation of a wooden door; and it even has a large round knocker, complete with fake hooks, carved into the stone in the upper right panel.

The door leads to a small rectangular chamber, room 3-C. Its meticulously hewn walls are decorated with architectural designs, giving the impression of an elegant and carefully ornamented room. Above the door, inside the room, the wall is decorated with a frame of delicately incised rhomboids painted dark-red.

Cut into the other three walls are arcosolia containing shallow burial shelves with rounded headrests at the ends. On the walls under the arcosolia are dark red framed panels in sunken relief, similar to the panel on the door to this chamber.

On the walls in the corners of the room are decorative motifs carved in low relief resembling Doric columns. At the far end of the room, a door in the wall leads to another chamber (3-D), which served as an ossuary depository. This door is similar to the one that led into the room.

We hope that someday these caves will be open to 046the public, especially now that recent political developments have calmed the tensions in east Jerusalem. The caves have been included in a list of approximately 60 archaeological sites in Jerusalem slated for development. Plans have already been drawn up for using the site to illustrate changing burial customs in Jerusalem during the 600-year period of Jewish, Roman and Christian occupation.

Plunderers, probably in ancient times, looted the Akeldama tombs described in the previous article. Not a single artifact remained when archaeologists entered those tombs: Only the chambers themselves, with their decorative elements, survived. In 1989, however, we discovered three cave tombs in Akeldama that had lain undisturbed for nearly 1,500 years and were filled with grave goods.1 Why were these three burial caves not emptied of their contents long ago? The answer is simple: No one knew they existed. As has often happened in Jerusalem when a road is being built, the phone rang at the Antiquities Authority. […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Footnotes

See Victor Hurowitz, “Did King Solomon Violate the Second Commandment?” BR 10:05.

The Ariston family may have been related to the Eros family from Cave 2, as several members of the Eros family were also buried in Cave 3. Ossuaries bearing the name Eros were located in room 3-D. However, since room 3-D is adjacent to Cave 2, both caves may have originally belonged to the Eros family, who then sold or gave one to the Ariston family. In any event, the two families seem to have had a common origin in the Diaspora and would naturally maintain close contact in their new homeland.

Endnotes

This excavation was carried out under the auspices of the Israel Antiquities Authority, with volunteers from the Antiquities Authority and Hebrew University’s Institute of Archaeology. For the final report on the excavation, see Gideon Avni and Zvi Greenhut, “The Aceldama Tombs—Investigations of Three Burial Caves at the Kidron Valley, Jerusalem,” Atiqot (forthcoming).

See L. Y. Rahmani, “Ancient Jerusalem Funerary Customs and Tombs,” Biblical Archaeologist vol. 44 (1981), pp. 171–177, 229–236; see also vol. 45 (1982), pp. 109–119, for various interpretations of the origin and development of this custom.

One example is the large Byzantine Christian burial cave found recently near Jaffa Gate in Jerusalem. See R. Reich, E. Shukrun and Y. Bilig, Excavations and Surveys in Israel 10 (1992), pp. 24–25.

Zvi Greenhut, “Burial Cave of the Caiaphas Family,” BAR 18:05. See also Dan Barag and David Flusser, “The Ossuary of Yehohanah granddaughter of the High Priest Theophilius,” Israel Exploration Journal 36 (1986), pp. 39–44; and Gladys Dickson, “The Tomb of Nicanor of Alexandria,” Palestine Exploration Fund Quarterly (1903), pp. 322–332.