018

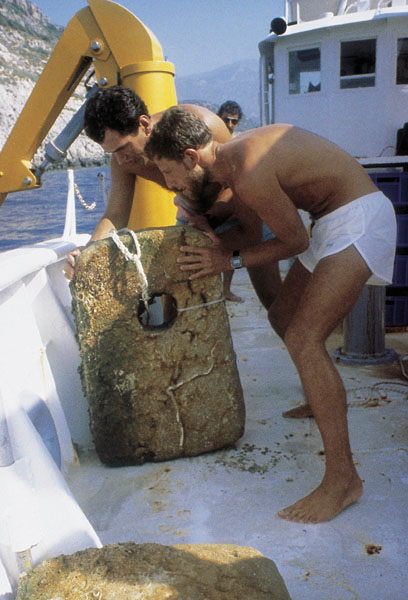

In the summer of 1982, a novice sponge diver working the waters off the southern coast of Turkey reported to his captain that he had seen “metal biscuits with ears” on the sea floor. The captain knew immediately that these “biscuits” were actually ancient metal ingots, so he alerted archaeologists from the Institute of Nautical Archaeology (INA) at Texas A&M University and Turkey’s Bodrum Museum of Underwater Archaeology. The diver, 020it turns out, had discovered a spectacular shipwreck from the Late Bronze Age (c. 1600–1100 B.C.).

Over the years INA survey teams had interviewed most of Turkey’s sponge divers, teaching them how to spot shipwrecks as they scoured the seabed for sponges. That is how the captain knew to inform the authorities. Two years later, in 1984, the INA began its excavation of the site.

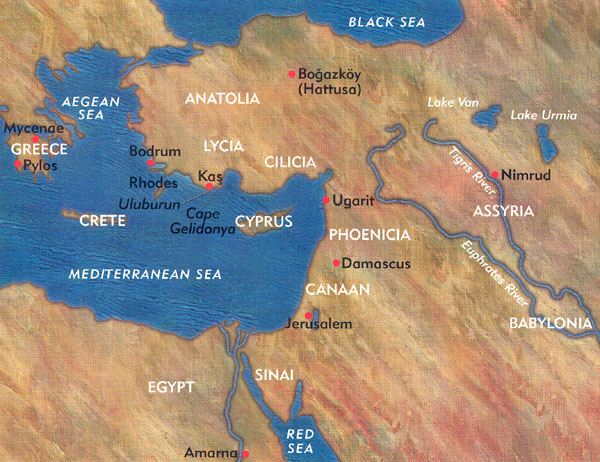

The ship went down only 200 feet from the east face of Uluburun (or “Grand Cape”), a little more than 5 miles southeast of the city of

The 11-year excavation of the Uluburun shipwreck—which logged more than 22,400 dives, or 6,613 hours of excavation time on the seabed—revealed one of the most impressive Late Bronze Age assemblages that has ever been found in the Mediterranean region.

The ship was probably plying a common commercial sea route, setting sail from the coast of Syria-Palestine and heading in a northwesterly direction. In the Late Bronze Age, ships traveling from east to west apparently hugged the southern coast of Turkey, sailed past Cape Gelidonya (as shown by the ship that sank 021there around 1200 B.C.)a and rounded Uluburun before passing the southwestern tip of Turkey. Our ship must have drawn dangerously close to shore, failing to clear the rocky Uluburun promontory. Had it passed through safely, the ship would probably have continued west to Greece, or sailed into the northern Aegean.

The ship’s cargo consisted mostly of raw materials (many only known, until the Uluburun excavation, from ancient cuneiform texts or Egyptian tomb paintings). The vast bulk of the cargo was some ten tons of Cypriot copper: 120 discoid, or “bun,” ingots; 5 “pillow-shaped” ingots of a seemingly earlier shape; three dozen previously unknown flat two-handled ingots; and 313 flat four-handled ingots, each weighing about 55 pounds (though they probably weighed about 60 pounds originally). These four-handled ingots are called “ox-hide” ingots, because it was once believed, erroneously, that they were cast to resemble dried ox hides. (According to this theory, each equaled the value of an ox and thus served as a kind of pre-monetary currency; but the discovery on the wreck of two-handled ingots helps to disprove this notion.) The four-handled ingots have also been called Cretan ingots in the belief that Egyptian artists associated them with the island of Crete. In fact, these ingots are more frequently associated with Syrian merchants and tribute-bearers.

Ingots in this cured ox-hide shape are widely distributed across the ancient world: from Sardinia to Mesopotamia, and from Egypt to the Black Sea, with a recent discovery made in Germany. Rather than serving as money, each ingot probably represented a quantity of raw copper subject to weighing and evaluation during commercial transactions. The shape itself would have evolved for ease of transportation over long distances on pack animals.

Recent chemical analyses of copper ingots from different sites in the Mediterranean have raised hopes of determining the sources of the copper. Scientists are performing lead-isotope analyses (that is, examining the isotopic composition, or the varying number of neutrons in the atom, of minute amounts of lead found as an impurity with 022the copper and matching these isotopic compositions with those of lead from different geological sources) and trace-element analyses (to determine whether copper from different sources contains the same combination of trace elements) in the hope of finding the sources of the copper ore used in making the ox-hide ingots.

Lead-isotope tests are being performed on all of the Uluburun ox-hide and bun ingots by Noél Gale and Sophie Stos-Gale at Oxford University’s Isotrace Laboratory in England. The preliminary results point to Cyprus as the source of almost all the Uluburun copper. Only a couple of small ingots have lead isotope ratios that deviate significantly from those of Cypriot copper, thus suggesting a different (as-yet unidentified) source for that ore.

Originally stowed in four rows transversing the ship’s hold, many ingots either slipped down the slope after the ship sank or were displaced as the hull settled under the tremendous weight of the cargo. But some retained their original lading, revealing that the ingots in each row had overlapped one another across the hull like roof shingles. The direction of overlap alternated from layer to layer, apparently to prevent slippage during transit. The ingots on the bottom layers were placed on beds of brushwood to protect the hull timbers.

The Uluburun ship has also yielded the earliest known well-dated tin ingots. Most of the tin ingots occur in the ox-hide form or in quarter-ox-hide sections (with each retaining one handle); the latter were cut from the complete four-handled variety. Other tin ingots came in rectangular slabs and sections of large, thick disks. A unique example was similar in shape to a stone anchor with a large hole at one end. This ingot, if its shape is original and not the result of deterioration, resembles metal ingots carried by bearers in Egyptian tomb paintings—though in the paintings the metals have been identified as silver or lead. Some of the tin had assumed the consistency of toothpaste and quickly disintegrated when disturbed by excavators. Although we do not yet know the exact amount of tin carried on the ship, a good estimate is about a ton—which, alloyed with the copper, would have made 11 tons of bronze.

Ox-hide ingots probably represent the form in which tin was transported from primary smelting areas at mines, or nearby processing centers, to distribution and manufacturing centers. References to tin trading in ancient texts hint that the source of the metal was located somewhere to the east, perhaps in Iran or even in Afghanistan or central Asia. These ox-hide ingots, therefore, presumably represent the preferred form in which tin was transported overland by donkey caravans—lending weight to the supposition that the form evolved for ease of handling. Tin ingots may have been cut into smaller sizes (for example, into the quarter-sections found 023on the Uluburun ship) after shipment for use in other commercial transactions. If so, the Uluburun tin ingots may not have been procured directly from the tin’s point of origin; rather, they were probably gathered—by barter, levies or gifts—from various sources.

Where did the Bronze Age metal smiths get their tin? This remains one of the greatest enigmas of the period. The large amount (one ton) of tin aboard the Uluburun ship may bring us a step closer to solving the problem, and promising (though negative) results are emerging. Lead isotope analyses appear to exclude eastern European, Cornish and Spanish tin deposits as the source of the Uluburun tin. Recently discovered tin in the Taurus mining districts in south-central Anatolia may be a potential source; indeed, lead isotope ratios of two lead fish-net sinkers from the wreck point to the Taurus districts. But archaeologists have shown that the Taurus tin was largely exhausted by the early Middle Bronze Age (around 2000 B.C.)—probably ruling out this region as the source of the Uluburun ingots. But the scientific analysis of the Uluburun tin continues, so we hope that more positive results will turn up soon.

The Uluburun ship held about 150 Canaanite jars—a kind of storage vessel found throughout the eastern Mediterranean and in Greece. The Uluburun jars were probably made somewhere north of modern Israel, perhaps in Syria. The smallest 024jars, three quarters of the entire lot, hold about seven quarts; some larger Canaanite jars are about twice that volume; and others, the largest type found aboard the ship, hold twice again as much, about 28 quarts. This last value may correspond to a bath, a Hebrew measure of volume. In the Hebrew Bible, the large bronze vessel, or the “molten sea,” that Hiram of Tyre casts for Solomon’s temple is said to have held “two thousand baths” (1 Kings 7:23–26).

One Canaanite jar was filled with glass beads, others with olives and perhaps also olive oil. But most of the jars contained a yellowish semi-solid material chemically identified as Pistacia resin, probably from Pistacia atlantica, a tree that grows in much of the Mediterranean region and is a close relative of the common pistachio tree. This resin, also known as terebinth resin (from the Greek terebinthos, which also gave us “turpentine”), was prized in antiquity as incense and may also have been used in making scented oils. The Uluburun ship was carrying about a ton of the stuff, making it the largest cargo aboard the ship other than the 11 tons of raw copper and tin. It is also the largest ancient deposit of terebinth resin ever found—and the first to be positively identified by modern science.

We can even pinpoint where the resin was harvested. Inside the jars containing the terebinth resin were land snails; the snails belong to a species with an extremely limited geographical distribution that has hardly changed in the last ten thousand years. From this evidence, we know that the resin was gathered in the region to the west of the Dead Sea in Israel (the snails were just stowaways).

Terebinth resin may be the sntr that Egyptian pharaohs imported from the Near East in Canaanite jars. The Theban tomb of Rekhmire, the chief minister (tjaty) of 025Thutmose III (1479–1425 B.C.), is decorated with paintings depicting royal storerooms filled with tribute; among the items are Canaanite jars labeled sntr. According to the annals of Thutmose III, over a period of five years the pharaoh imported 2,445 gallons of sntr a year—about nine times the amount of terebinth resin on the Uluburun ship.

Also among the cargo were about 170 glass ingots, the earliest intact glass ingots ever found. These cobalt-blue, turquoise and lavender glass disks are probably the mekku and ehlipakku listed on cuneiform tablets from Ugarit (on Syria’s Mediterranean coast) and Tell el-Amarna (in Egypt), Akhenaten and Nefertiti’s capital, as items traded from the Syro-Palestinian coast. They are also probably the “cakes of lapis lazuli and turquoise” (as opposed to the “genuine” stones) listed as tribute from Syria on a relief at Karnak from the time of Thutmose III. The Uluburun cobalt-blue glass ingots are chemically identical to blue glass from 18th Dynasty Egypt (1550–1295 B.C.) and to Mycenaean glass pendant beads—suggesting a common source for all.

Some of the Uluburun ship’s more exotic cargo was from tropical Africa: logs of what the Egyptians called ebony, now known as blackwood (Dalbergia melanoxylon); elephant tusks; hippopotamus teeth; and ostrich eggshells, which would probably have been made into fancy vases and other vessels. More local exotica, from around the Mediterranean, included murex shells, possibly used as an ingredient in making incense, and tortoise carapaces, used as sound boxes for musical instruments.

An astonishingly rich collection of gold Canaanite jewelry also surfaced during the excavation. Among the pieces are pectorals, medallions and pendants. One of the pendants bears a repoussé figure of a nude female holding a gazelle in each hand—almost certainly a Canaanite fertility figurine, similar to pendants found at Ugarit. Four gold medallions were recovered from the wreck—all decorated with a repoussé four-pointed star and curved rays—including the largest gold Canaanite medallion of its type ever discovered, though a similar but poorly preserved silver medallion has been found in Palestine. A gold pectoral from the ship, depicting a falcon with outstretched wings clutching a hooded cobra in each claw, also resembles examples from the Levant. But the origin of the largest gold object on the ship, a biconical goblet, is not known.

Among the Egyptian objects—made of gold, silver and steatite (a grayish green 026soapstone)—was a gold scarab inscribed with the name of Nefertiti, the wife of Pharaoh Akhenaten (1352–1336 B.C.). (This scarab, as we will see, provides an interesting clue to the date of the shipwreck.) Another scarab names Thutmose I (1504–1492 B.C.). Most of the other scarabs from the wreck are even earlier, dating to the Second Intermediate Period (17th and 16th centuries B.C.), and either have unreadable signs or are inscribed with good-luck or prophylactic signs.

The ship was carrying two duck-shaped ivory cosmetic boxes with hinged-wing covers, a trumpet carved from a hippopotamus tooth, and more tin vessels than had previously been found in the entire Bronze Age Near East and Aegean. Beads of glass, agate, carnelian, quartz, gold, bone, amber (chemically identified as being of the Baltic variety), seashell, ostrich eggshell and faience have been found by the thousands. There were also several dozen seashell rings, probably inlaid with bits of colored glass whose various shapes are preserved in the bitumen affixing them to the surface of the rings.

As we might expect, there was also food aboard the ship, some probably as cargo and some for consumption on the journey. The excavations revealed traces of almonds, pine nuts, figs, olives, grapes (or raisins or wine), black cumin, sumac, coriander, safflower and whole pomegranates, along with a few grains of wheat and barley. The passengers and crew also dined on fresh fish; we found net sinkers, netting needles, fish hooks, a bronze trident and a barbed fish spear.

Nonetheless, a cargo does not identify the nationality of the ship that carries it. Better evidence for a ship’s home port may come from a thorough study of its galley wares, the crew’s personal effects and such items as tools used for repairs made during the voyage. On the seabed, near a scepter-mace of a type known from Romania and Bulgaria, lay a bronze female figurine, with her hands extended forward. Her head, neck, hands and feet are covered with sheet gold. In the Amarna Letters—diplomatic correspondence of the pharaohs Akhenaten and his father Amenophis III with petty monarchs in Canaan and elsewhere—gold-clad bronze statuettes, made in the likeness of actual royal figures, are listed as gifts presented to the pharaoh. Perhaps this statuette depicts the wife or daughter of a Syro-Palestinian king who was sending the figurine to another king as a gift. More likely, however, the statuette was a cult or votive figurine intended to protect the ship from peril at sea and to ensure the success of the venture.

The Uluburun ship also had a large number of tools—sickles, drills and drill bits, chisels, axes and whetstones—and bronze weapons. Among the weapons were arrowheads, spearheads, maces, daggers and swords of Canaanite, Mycenaean and probably Italian types. The best-preserved sword is a heavy Canaanite weapon cast in one piece, with a flanged hilt inlaid with ivory and African blackwood (ebony). Two nearly identical daggers are similar to the Canaanite sword and may be companion pieces to it. A good parallel for the Uluburun daggers comes from a 14th-century B.C. merchant’s tomb just north of the ancient tell of Akko, on the Mediterranean coast of modern Israel.

Two swords of slightly different sizes are typical Aegean products. Their single-piece construction, with ribbed blade, flanged grip, and cruciform shoulders, is typical of the 14th century B.C. These swords have a broad flattish midrib with fine grooves instead of the distinctive high midrib of mostly earlier weapons. The loss of the midrib during the 14th century is recognized as a development leading to thicker, double-convex blades without true midribs. These two swords, therefore, constitute a transition to later, more advanced 027sword forms developed for cutting and slashing rather than for thrusting.

Some of our best information about the Uluburun ship’s cultural affinity comes from its most mundane artifacts: merchants’ weights. The Uluburun weights are the largest and most complete group of Late Bronze Age weights to have come from a single undisturbed site. They provide us with complete sets of weights necessary for a merchant to ply his craft.

Although most of the weights are made of stone sculpted in geometric shapes, the wreck has yielded the largest set of Bronze Age zoomorphic weights found so far, including a sphinx, bulls, cows, a calf, ducks, frogs, lions and a fly. A large disk-shaped weight bears the figure of a cow herder kneeling before three of his calves. All of the zoomorphic weights are bronze, some of them cast hollow and filled with lead, which, in some examples, has expanded with corrosion and severely damaged their bronze shells.

The weights mostly correspond to a system based on a unit mass of about a third of an ounce, a standard commonly used along most of the Syro-Palestinian coast, on Cyprus and in Egypt. The number of weight sets suggests that there were at least three merchants on board the ship—a conclusion supported by the discovery of three sets of pans for balance scales—with possibly a fourth, chief merchant who used the fancier zoomorphic weights. From this evidence, it is almost certain that Semitic merchants were traveling on the ship. (Of the 149 weights, only one appears to represent an Aegean weight.)

Other evidence for the ship’s origin comes from its 24 stone anchors—which the ship’s builders and outfitters would likely have procured from a nearby location. The Uluburun ship’s anchors are of a type virtually unknown in the Aegean but often found off the coast of Israel, as well as in walls of temples and tombs in Ugarit, Byblos (on the Phoenician coast) and Kition (in Cyprus). Such anchors seem to have been manufactured at Tell Abu Hawam and Tel Nami, sites on the Mediterranean coast near Haifa, Israel.

The ship most likely embarked from a Syro-Palestinian port, such as Ugarit. Syrian oil lamps used aboard the ship and the ballast stones recovered from the site strengthen this view. The ship’s story may have been documented in the most intriguing objects found aboard the ship: two boxwood diptychs, or writing tablets (see “Recovered! The World’s Oldest Book”), found inside a large storage jar that probably contained pomegranates. The interior surfaces of these tablets were once covered with wax so that a message could be inscribed with a bone or a wooden stylus. Unfortunately, the wax writing surfaces, which may have contained bills of lading (perhaps indicating the ship’s origin), are missing. These writing tablets are almost certainly Near Eastern in origin—028a view supported by the discovery of ivory hinges at Megiddo and elsewhere in the Near East similar to those used in the Uluburun diptychs.

Built of cedar, the 50-foot-long ship was constructed in the “shell-first” technique, with pegged mortise-and-tenon joints holding its planks together and to the keel. Used in Greco-Roman ships, this technique contrasts with the more familiar “skeleton-first” construction, whereby the ship’s planking is formed around a pre-erected skeleton. It appears that the keel of the ship, which is wider than it is high, originally protruded beyond the outer planking surface by only an inch or so. This timber would have served as the ship’s spine, as well as to protect the planks and support the ship when beached or hauled ashore; but unlike keels of later sailing ships, this rudimentary keel would have done little to help the ship hold course or sail nearer the wind.

The excavation also found the remains of wicker fencing, probably used to keep the sea from rolling onto the ship during rough weather. This is reminiscent of the weather fencing on all Syrian ships depicted in nearly contemporaneous Egyptian tomb paintings. The wicker fencing also recalls a passage from Homer’s Odyssey: In Book V, after Calypso agrees to allow Odysseus to leave her island, he builds a ship and fences “her stem to stern with twigs and wicker, / bulwark against the sea surge” (lines 282–283).

When exactly did the Uluburun ship go down? The Nefertiti scarab proves that the ship could not have sunk before the reign of Akhenaten, about 1350 B.C. But an even later date is likely. The Nefertiti scarab was found near a jeweler’s hoard of scrap gold, silver and electrum (an alloy of gold and silver); if the scarab was part of this hoard, then the Uluburun ship probably sank some time after the death of Nefertiti, when her scarab would have lost its symbolic royal value and would have simply become a piece of jewelry, a curiosity or simply gold bullion. Dendrochronological tests on a single piece of firewood aboard the ship, moreover, give the year 1305 B.C. So the ship probably sank around 1300 B.C.

The Uluburun shipwreck thus belongs to a well-documented segment of history, the period of the Amarna Letters and its aftermath. The only extant depiction of a Mediterranean merchant venture from the mid-14th century B.C. is a scene in the tomb of Kenamun, who served as mayor of Thebes during the reign of Amenophis III (1390–1352 B.C.). Kenamun’s Theban tomb contains a painting depicting the arrival of a Syrian merchant fleet in an Egyptian port. Porters are shown unloading Canaanite jars and pilgrim flasks similar to those found on the Uluburun wreck. Some of the crew in the painting wear roundels on their necks that may represent Canaanite star-disk pendants of the 029type recovered during the Uluburun excavation. Other nearly contemporaneous Egyptian tomb paintings depict tribute bearers carrying elephant tusks, ebony (African blackwood) logs, Canaanite jars and ox-hide ingots—all goods recovered from our Bronze Age shipwreck.

The ox-hide ingots from Uluburun make up about 325 talents of copper. The Amarna Letters refer to shipments of 100, 200 and, in one instance, possibly 500 talents of copper from Alashia (Cyprus) to Egypt. The Amarna Letters also mention glass ingots, elephant tusks, gold jewelry, silver, statuettes and weapons among the royal gifts—all of which are matched by finds on our wreck. Could this cargo, then, represent a royal shipment of the kind exchanged between the Syro-Palestinian coast, Egypt and Cyprus—as vividly described in the Amarna Letters?

The ship was undoubtedly sailing to a region west of Cyprus, but her ultimate destination can be only surmised, based on the objects she was carrying. Some of the Mycenaean objects on board have close parallels on Rhodes, an island that appears to have played an important role as a commercial redistribution center for the Aegean. So maybe the ship was headed to Rhodes. Another possible destination is Crete. Cypriot pottery, ox-hide ingot fragments and Canaanite jars have recently been found at Kommos on Crete, and we know that ships from Ugarit visited Crete during this period.

The best bet for the ship’s destination, however, is the Greek mainland—with its impressive cargo destined to be sold or presented to one of the great Mycenaean cities, perhaps Tiryns or Mycenae.

The excavations turned up two sets of personal items of Mycenaean origin—making it almost certain that two Mycenaeans were traveling on the ship. Perhaps these gentlemen were only passengers. We know that they were not merchants, for no weight sets based on the Aegean standard were found on the ship. It does not seem farfetched to suggest that these Mycenaeans might have been overseeing an official—or royal—shipment of 059valuable goods from the Levant to the Peloponnesus.

The Uluburun ship demonstrates how Near Eastern goods reached the Late Bronze Age Aegean. The ship’s cargo, with goods produced by nine or ten different ancient cultures, appears to have been an official shipment of goods intended for a single specific destination; clearly, the Uluburun ship was not a roving merchant vessel that traded in any old port. The ship’s enormously rich cargo was likely placed in the care of an official who represented the king’s interest, who was entrusted to present the prestigious gifts to another king, and who probably engaged in a little private trading of his own on the side.

Maybe we can be more specific. Was the ship headed to the prosperous Mycenaean mainland? And were the two Mycenaeans on board charged with seeing this royal cargo safely into port? If so, Uluburun, unfortunately for them (though fortunately for us), got in the way.

Over the years, the project has been generously funded by the INA Board of Directors and by grants from the National Endowment for the Humanities, the National Science Foundation, the National Geographic Society, Texas A&M University, and the Institute for Aegean Prehistory.

In the summer of 1982, a novice sponge diver working the waters off the southern coast of Turkey reported to his captain that he had seen “metal biscuits with ears” on the sea floor. The captain knew immediately that these “biscuits” were actually ancient metal ingots, so he alerted archaeologists from the Institute of Nautical Archaeology (INA) at Texas A&M University and Turkey’s Bodrum Museum of Underwater Archaeology. The diver, 020it turns out, had discovered a spectacular shipwreck from the Late Bronze Age (c. 1600–1100 B.C.). Over the years INA survey teams had interviewed most of Turkey’s sponge divers, […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Footnotes

The shipwreck at Cape Gelidonya, about 70 miles east of Uluburun, has been dated to about 1200 B.C. by radiocarbon tests on brushwood found on the ship. Spotted by a sponge diver in 1954, the wreck was excavated in 1960 by George F. Bass, then at the Museum of the University of Pennsylvania—the first shipwreck excavation carried to completion on the seabed. The ship’s cargo included tin ingots and copper ox-hide ingots from Cyprus, as well as Mycenaean, Syrian and Cypriot pottery. Since the merchant’s weights found on the ship were all of Syro-Canaanite or Cypriot origin, scholars believe that the Cape Gelidonya ship, like the Uluburun ship, embarked from a Levantine port.