The sky was clear and blue that spring day in April 1969. The early morning sun glanced off the mauve-colored Mount of Olives. Tiny wild flowers dotted the hillside. The air was fresh and fragrant after an unusually heavy rain the night before.

It was a perfect time to explore the walls and gates of Jerusalem. I was then a graduate student at the American Institute of Holy Land Studies and was studying Biblical archaeology under Professor Moshe Kochavi of Tel Aviv University. I had taken a special interest in the topography of Jerusalem.

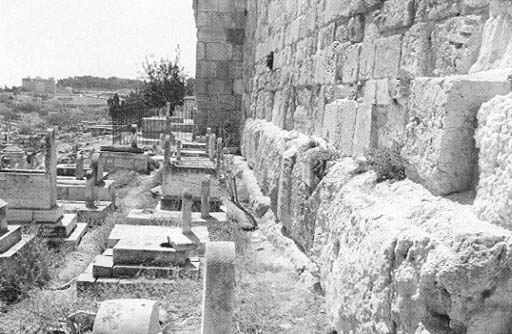

I slung my camera over my shoulder and headed for the outside of the eastern wall of the Old City. I would follow this wall through the Moslem cemetery to the Golden Gate, which was easily worth a morning’s exploration. As I breathed the spring air deeply, I had no idea that I would soon be knee-deep in human bones!

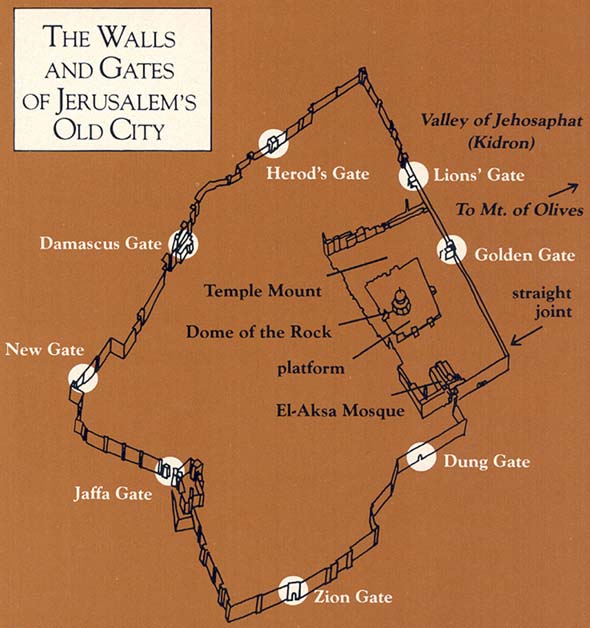

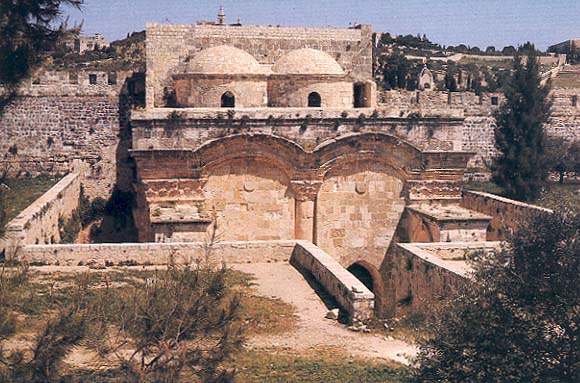

The Golden Gate is one of the most beautiful of Jerusalem’s eight Old City gates. Today the two arches of the gate are sealed shut and stand in silent contrast to the hubbub of the Jaffa Gate on the west and the Damascus Gate on the north. Scholars are not sure when the Golden Gate was mortared in. It may have been blocked for security reasons during the various Arab-Crusader conflicts from the 11th to the 13th centuries. Or it may have been closed by the Ottoman Turks after Suleiman the Magnificent rebuilt the walls of Jerusalem from 1539 to 1542. The most recent clearing and strengthening of the gate was done by the Turkish authorities in 1891.

Though security probably was the main reason for the gate’s closure, some historians wonder if the gate’s Biblical associations may also have been an influence. The final judgment of mankind and the messianic associations of Jewish, Christian and Moslem traditions are linked with this gate. In the Middle Ages, religious Jews prayed there as they do now at the Western or Wailing Wall. Christians have always associated the Golden Gate with Palm Sunday as well as with the second coming of Jesus. Moslems wanted to be buried near it because the Koran connects Allah’s final judgment with this gate. Over the centuries, as the political climate changed, the Jewish and Christian presence near the gate shrank, while the Moslem cemetery enlarged along the city’s eastern wall to the gate’s very portals.

Most of the last judgment and messianic associations with the Golden Gate stem from the Bible. In Zechariah 14:4–5, the prophet delivers an oracle on the day of the Lord’s coming. “On that day his feet shall stand on the Mount of Olives which lies before Jerusalem on the east; … Then the Lord your God will come, and all the holy ones with him.” From this passage, it would seem that the Lord’s entrance into the city would be from the east, perhaps through this gate.

The prophet Joel also delivers an oracle on the “Day of the Lord.” It begins with this famous passage: “And I will give portents in the heavens and on the earth, blood and fire and columns of smoke. The sun shall be turned to darkness, and the moon to blood, before the great and terrible day of the Lord comes.” (Joel 2:30–31) The oracle goes on: “I will gather all the nations and bring them down to the Valley of Jehosaphat, for there I will sit to judge all the nations round about.” (Joel 3).

Jehosaphat is not only the name of an Israelite king; it also means “judgment,” and therefore the Valley of Judgment is probably another name for the Kidron Valley, which lies east of Jerusalem between the city itself and the Mount of Olives. Accordingly, on the day of the Lord forecast in Joel, the nations may be gathered in the valley east of Jerusalem and be judged by God. Judgments were customarily rendered in the gates of a city (see Genesis 19:1, 23:10), so presumably the Lord would render His judgments at the eastern gate of Jerusalem, near the Temple. Thus the association of Judgment Day with the Golden Gate.

Jesus’s triumphal entry into Jerusalem on Palm Sunday (the Sunday before Passover and the last week of his ministry) was probably through the city’s eastern gate. Jesus’s entry into Jerusalem is recorded in all four Gospels. According to Luke 19:37, “As he was now drawing near, at the descent of the Mount of Olives [east of Jerusalem], the whole multitude of the disciples began to rejoice and praise God with a loud voice for all the mighty works that they had seen, saying, ‘Blessed is the King who comes in the name of the Lord!’” Mark adds that Jesus entered the city and went directly to the Temple (Mark 11:11), possibly through the eastern gate. (Some of the crowd assembled along the road may have been looking for the fulfillment of the prophecies in Zechariah and Joel.)

In 614 A.D., the Persians invaded and destroyed Byzantine Jerusalem. The Christians recaptured the city under Emperor Heraclius and rescued “the true cross” from the Persian invaders. On March 21, 629 A.D., the cross was returned to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in a regal procession through the Golden Gate, similar to that of the first Palm Sunday 600 years earlier.

With the coming of Islam, Moslems too began to associate the Golden Gate with messianic expectations. The suna, traditions of the Prophet Mohammed, likens the last judgment to a narrow path on the blade of a knife stretched from a mountain to the gate of heaven. Many Moslems understood this symbolic knife blade to span the Kidron Valley from the Mount of Olives to the Golden Gate. The two arches of the Golden Gate therefore have Arabic names associated with the final judgment: the northern arch is called the Gate of Repentance and the southern arch is called the Gate of Mercy. (Jews also refer to this gate as the Mercy Gate.)

These ancient prophetic and apocalyptic associations with the eastern gate of Jerusalem have affected the appearance of today’s Kidron Valley outside the Golden Gate. On the slopes of the valley are Jewish, Christian and Moslem cemeteries. The ancient Jewish cemetery, the oldest in continuous use anywhere in the world, blankets the western slope of the Mount of Olives. The Christian cemetery lies deep within a wall at the bottom of the valley. The Moslem cemetery covers the hillside below and adjacent to the Golden Gate, along the eastern wall of the Old City. For centuries, the faithful of these religions have wanted to be buried as close as possible to the Golden Gate and the Mount of Olives. The thousands of graves paving the Valley of Judgment bear witness to the faith of the dead, their remains silently waiting in the dry earth like Rose of Jericho seeds waiting for the rain of the resurrection and the last judgment.1

“Golden Gate” is actually the Christian name for the eastern gate of Jerusalem. This name was probably derived from New Testament references to a gate known as the Beautiful Gate (Acts 3:2, 10). How did “Beautiful” become “Golden”? In the earliest Greek New Testament, the word for “beautiful” is oraia. When Jerome translated the New Testament into Latin in the fourth century, he changed the Greek oraia to the similar-sounding Latin aurea, rather than to the Latin word for “beautiful.” So the Latin Vulgate text read “Golden Gate” instead of “Beautiful Gate.”2

“Beautiful or Golden,” I thought to myself as I proceeded on my walk that spring morning. “It doesn’t matter. It’s both!” When I knelt down in front of the Golden Gate to take a picture, I was filled with these pleasant thoughts. I was unaware that my feet were gradually sinking into the muddy earth of the Moslem cemetery. The heavy night rain had not yet evaporated, but I was concentrating on the view in my camera, not my sinking feet. Suddenly the earth gave way beneath me. I felt as though I was part of a rock slide. Down I went into a hole eight feet deep.

I was disoriented but uninjured. I picked myself up and tried to focus my eyes in the dim light that came through the hole above my head. I suddenly realized that I was standing amidst the bones of 30 to 40 human skeletons apparently thrown together in a mass burial. Some of the bones were still connected by cartilage, which indicated interment within the last hundred years or so—relatively recently in Middle Eastern chronology. I wondered if the burial of such a large number of people in an unmarked grave meant that these people had died suddenly as a result of some disaster—battle, famine, or plague?

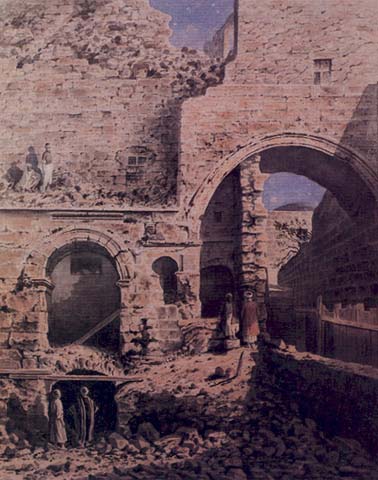

Once I realized that enough stones had fallen into the tomb with me to construct a platform from which I could chin myself and thereby get out, I was able to concentrate more closely on my surroundings. I was amazed to see an ancient wall below the Golden Gate exposed in front of me. The Gate itself is built into a turret that protrudes about six feet from the wall. The underground stones of the wall south of the turret were large and imposing. Then I noticed with astonishment that on the eastern face of the turret wall, directly beneath the Golden Gate itself, were five wedge-shaped stones neatly set in a massive arch spanning the turret wall. Here were the remains of an earlier gate to Jerusalem, below the Golden Gate, one that apparently had never been fully documented.3

I attempted a few pictures, though I had to use time exposures because I had no flash equipment. Then I scurried out of the hole and returned to school.

The next day I again went to the Golden Gate, but this time with flash equipment. Unfortunately, the caretakers of the cemetery had acted with efficiency quite uncharacteristic of the Middle East. The tomb into which I had fallen had already been repaired!

In 1972, while showing the tomb to my brother, I noticed a new hole in the tomb. I had previously told Dr. George Giacumakis, now president of the Institute of Holy Land Studies in Jerusalem and a member of BAR’s Editorial Advisory Board, of my experience at the tomb. Happy for the opportunity to photograph the tomb and arch under better conditions, I returned with Dr. Giacumakis, Professor Roy Hayden of Oral Roberts University, and Ginger Barth, a member of the Institute staff. We lowered ourselves into the tomb and re-photographed the wall and the stones of the arch. Shortly thereafter, the tomb was cemented over permanently. That tomb and others directly in front of the Golden Gate were then enclosed by a protective iron fence in 1978. It is unlikely that anyone will have an opportunity in the foreseeable future to examine the remains of this ancient gate to Jerusalem. That being the case, it is especially important to give a detailed description of both the visible upper gate and the lower gate beneath it.

How old is the gate below the Golden Gate? Could it have been the gate through which Jesus entered the Holy City? Unfortunately, it is difficult to date this underground gate precisely. All that can be said with confidence is that the Lower Gate—as I shall identify the gate below the Golden Gate—is older than the Golden Gate itself.

Without the possibility of an archaeological excavation there are only two clues to estimating the age of the Lower Gate: First, the relationship of the arch of the Lower Gate to the gate above it; second the relationship of the Lower Gate to the lower courses of masonry just above ground along the eastern wall of the Old City.

The Golden Gate is the oldest of all the present gates of the Old City. Six of the other seven present gatesa were built by Suleiman the Magnificent from 1539 to 1542, when he rebuilt the walls of Jerusalem. Jaffa Gate, Damascus Gate, Zion Gate, Lion’s (Saint Stephen’s) Gate, Dung Gate, and Herod’s Gate all were built by Suleiman. The New Gate was added in modern times. The Golden Gate was the only ancient gate preserved when Suleiman reconstructed the walls of Jerusalem.

Most scholars believe that the Golden Gate with its beautiful double arches was built in the Byzantine Period.4 In a soon-to-be-published paper on the gates to the Temple Mount, Meir Ben-Dov will argue, however, that the Golden Gate was built in the Early Arab Period, not long after the Arabs captured Jerusalem in 638 A.D. Ben-Dov calls attention to the similarities between the Golden Gate and the other entrances to the Temple Mount (or Haram esh-Sharif as it is called in Arabic) built during the Early Arab Period. Ben-Dov also notes the absence of crosses in the ornate arches, an indication, he says, that the Golden Gate was constructed after the Byzantine period.

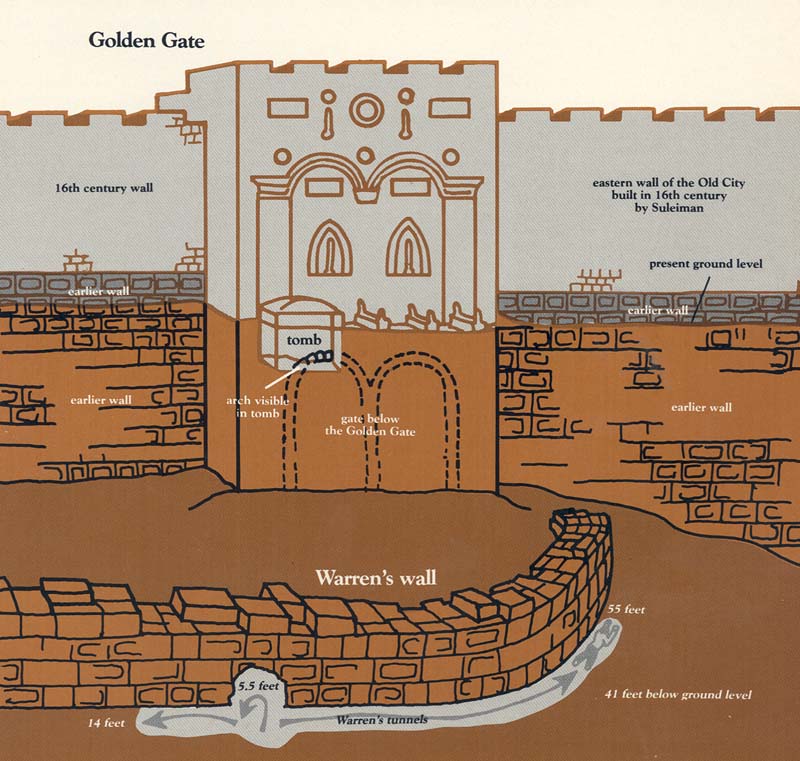

The arch of the Lower Gate is under the southern arch of the present Golden Gate. Both arches seem to be on precisely the same line. Moreover, both gates are on the same vertical plane—built into a turret that extends six feet outward from the wall line.

Some scholars have suggested that the Lower Gate dates to the period just preceding the Byzantine—the Late Roman Period. Beginning in 130 A.D., Hadrian rebuilt Jerusalem as a Roman colony named Aelia Capitolina. Could this Lower Gate have led to Hadrian’s Temple of Jupiter built over the destroyed Jewish Temple? Two arches most scholars date to Aelia Capitolina are visible in the Old City today. One is the gate beneath the Damascus Gate. The other is the arch that passes through the convent of the Sisters of Zion, the Ecce Homo arch, so-called because when it was discovered, it was attributed to the time of Jesus and identified as the place where Pilate said “Behold, the man” (“Ecce homo”). These two Aelia Capitolina arches are composed of stylized concentric arcs that recede slightly from the top of the arch as their radii become smaller. The arch beneath the Golden Gate, on the other hand, is constructed of smooth, wedge-shaped stones. This difference in masonry makes it difficult to argue that the arch of the Lower Gate dates to the Late Roman period. The masonry of the Lower Gate is certainly very different from the two known arches that are commonly dated to this period.

The gate below the Golden Gate could conceivably be Herodian (37 B.C. to 70 A.D.) but this too is unlikely. Josephus, the first-century historian, clearly states that the eastern Temple enclosure wall was the only one that Herod did not rebuild. (The Jewish War V, 184–189 [v. 1]).

A comparison of the Lower Gate with the wall into which it is built might help date the gate. Unfortunately, most, but not all, of this wall is underground.

In the 16th century, when Suleiman began to build the wall on either side of the Golden Gate, he found that both sides of the gate were leaning outward and needed strengthening. To buttress the gate, he built perpendicular arches on the interior, and on the exterior he replaced some older stones with wider ones in the corners.

North and south of the Golden Gate, Suleiman built a new wall on the line of an earlier wall. This earlier wall, built of large handsome ashlars 2.5 feet high and 4 to 5 feet long, can still be seen for two or three courses above ground (below the line of Suleiman’s masonry). Each ashlar has a recessed margin three to six inches wide. Inside the marginal draft, the face of the stones projects about six inches.

The ashlars in this earlier wall do not join tightly together; they are separated by uneven spaces. This odd construction suggests that the stones were restacked after an earlier collapse. The arch I found is about four courses below this early wall adjacent to the Golden Gate. The floor of the underground gate is probably about eight courses below the arch that surmounts the gate. Thus, the arch of the Lower Gate probably belongs to the gateway constructed into this massive lower wall.

This ancient wall may have been a double wall. A wall discovered in 1867 by Captain Charles Warren may have been part of the outer wall of this double wall. The story of Warren’s exploration of this outer wall is full of 19th-century romance and excitement. Warren was commissioned by the London-based Palestine Exploration Fund to explore the entire Temple Mount area.5 But when Warren arrived in Jerusalem, the local governor denied him permission to conduct large-scale digging; the governor feared that excavations might dangerously weaken the Haram esh-Sharif enclosure wall.

Warren determined to be as inconspicuous as possible—he went underground. First he sank deep shafts in several places adjacent to the Temple Mount enclosure walls. In this way Warren explored the walls of the Temple Mount below ground. On the east side, however, the Moslem cemetery just outside the wall prevented his sinking a shaft adjacent to the wall. To avoid the cemetery, he had to sink a shaft some distance further to the east and then drive an underground tunnel back to the wall.

Warren sank his shaft in the lower Kidron Valley, 143 feet east of the Golden Gate. When he reached bedrock, he began tunneling westward along the bedrock up the slope. However, he was forced to come to an abrupt halt 46 feet east of the present wall when he encountered another, massive wall parallel to the present east wall. Warren tried to tunnel over the wall, but it proved too high and he feared that some of the tombs in the cemetery overhead might cave in on him if he continued. He tried to chisel through the wall, but abandoned this time-consuming effort when, having chiseled 5.5 feet into it, he found yet another course of masonry blocking his way.

Then Warren tried to tunnel around this obstructing wall in his effort to reach the eastern wall of the Temple Mount. First he tunneled south along the obstructing wall for 14 feet and then decided it might be shorter if he dug north. At last, when the tunnel had reached a length of 55 feet, the wall began turning west. Warren’s expectation of reaching the eastern temple enclosure soared! But a sudden underground landslide made further progress too dangerous, and Warren was forced to abandon the effort. There seemed to be no way to tunnel around this massive obstructing wall.

Although Warren was unable to reach the eastern Temple Mount enclosure wall, he did make his usual careful observations. The most important of these, for our purposes, is that the massive underground wall 46 feet in front of the Golden Gate resembled the two or three lower courses of masonry exposed above ground on either side of the Golden Gate. Warren described the masonry of the underground wall as follows: “ … large quarry-dressed blocks … so far similar to the lower course seen in the sanctuary wall near the Golden Gate, that the roughly dressed faces of the stones project about six inches beyond the marginal drafts, which are very rough.”

Warren measured the ashlars in the underground wall and found that they were similar in size to the ashlars in the two or three courses exposed above ground in the eastern wall on either side of the Golden Gate. Warren did note one difference, however. Instead of lying side by side, the stones in the underground wall were as much as a foot apart with the space between them filled with smaller rocks and plaster. Warren had examined the part of the wall that rested on bedrock; at that level, a rough foundation wall was apparently all that was required.

From the similarity in the ashlars, as well as the fact that Warren’s underground wall takes a 90 degree turn west directly toward the Golden Gate, we can assume that the wall Warren found is associated with the lower two or three courses of masonry exposed above ground on either side of the Golden Gate.

Warren also compared the masonry in the lower two or three courses of the eastern wall adjacent to the Golden Gate with the masonry in the eastern wall to the right (north) of the famous “straight joint.” The “straight joint” is a vertical seam in the masonry of the eastern wall of the Old City, 105 feet north of the southeastern corner of the Temple Mount. The straight joint or straight seam was obviously created by an addition to the eastern wall on its southern end. The addition, most are agreed, was built by Herod the Great, to extend the southern end of the Temple Mount.

But who built the wall north of the straight joint? The question has significance here because the masonry appears to be the same as that in the lowest two or three courses visible above ground on either side of the Golden Gate, as well as that of the large ashlars with marginal drafts Warren found below ground in the wall that curved toward the Golden Gate.

The masonry north of the straight joint appears to have two building phases, though the stones in both phases have the same appearance. The lowest seven courses are arranged in alternating rows of headers (short facings) and stretchers (long facings); the stones themselves are tightly joined. Above these seven courses, however, the pattern of alternating rows of headers and stretchers is abandoned, and the stones are not snugly fitted together—as if the upper courses had once collapsed and were then restacked, like the two or three exposed courses of masonry adjacent to the Golden Gate.

Scholars disagree as to who built the wall north of the straight joint. Some, like Professor Michael Avi-Yonah, who died in 1973, attribute the masonry to Herod the Great. The Herodians, Avi-Yonah said, used more than one kind of masonry. Herod, the emperor, built the wall to the right of the straight joint. To its left, one of Herod’s descendants, in the so-called Herodian period, later added the “Royal Portico” to the southern end of the Temple Mount, using a different kind of masonry. (In support of Avi-Yonah’s theory is the observation by Josephus that an earlier portico built by Herod the Great burned and was rebuilt later.)

There are several difficulties with Avi-Yonah’s dating. There is no suggestion in the literary sources that either Herod or his successors ever did any building (such as the underground wall Warren found) along the eastern side of the Temple platform. Josephus records that Herod Agrippa II (53–66 A.D.) considered raising the height of the east wall in order to employ 18,000 men left without work after completion of the construction of the Temple. The people “urged the king to raise the height of the east portico. This portico was part of the outer temple, and was situated in a deep ravine [The Kidron]. It had walls four hundred cubits long and was constructed of square stones, completely white, each stone being twenty cubits long and six high. This was the work of King Solomon, who was the first to build the whole temple. The king [Agrippa] reasoned that it is always easy to demolish a structure but hard to erect one, and still more so in the case of this portico, for the work would take time and a great deal of money. He therefore refused this request of theirs; but he did not veto the paving of the city with white stone.” (Jewish Antiquities XX, 219–223, [7]).

If, as Avi-Yonah says, the eastern temple enclosure wall was constructed by Herod, how could it have been in need of renovation in 64 A.D. and how could it have appeared so ancient that it was believed by the people to be 1,000 years old, from King Solomon’s time? This account in Josephus forces us to conclude that until the eve of the destruction of the Temple, the eastern walls and porticoes remained old, and were, therefore, called “Solomon’s Porticoes.” (See also Acts 5:12.)

Basing their conclusions on archaeological evidence, many scholars date the masonry north of the straight joint to a period earlier than the Herodian. However, they disagree as to just how much earlier.

For example, Dr. Yoram Tsafrir6 suggests that the masonry to the right of the straight joint dates from the Hellenistic Period and is possibly the work of Alexander Yannai (103–76 B.C.). There are similarities between this wall and the Alexandrium and Machaerus fortresses also believed to have been constructed by Yannai. And Tsafrir suggests another possible builder from the Hellenistic Period—Simon the Just, High Priest from 219–196 B.C., might have built this eastern wall. Warren’s underground second wall of similar masonry parallel to this eastern wall presents an intriguing correlation to Simon’s building projects mentioned in Ben Sira 50:1–2: “Simon the high priest, son of Onias, in his life repaired the house [of God], and in his time fortified the temple. He laid the foundations for the high double walls, the high retaining walls for the temple enclosure.” Though the meaning of “double walls” is obscure, the reference here may be to Warren’s wall along the eastern temple enclosure.

Other scholars, such as Dame Kathleen Kenyon7 and Maurice Dunand, whom Kenyon calls “the doyen of archaeology of the Phoenician coast,”8 have opted for an even earlier date—in the Persian period (the end of the sixth century B.C.)—for the masonry to the right of the straight joint. They base this dating on similarities with Persian period walls found in Sidon and Byblos. A few years before her death in 1978, Kenyon wrote that the wall dated to the period of the return to Zion from Babylonian captivity, when the Jews reconstructed Jerusalem (2 Chronicles 36:23, Ezra 1:2–3, 6:5–8). For example, in Digging Up Jerusalem, Kenyon stated that the wall was a result of several reconstructions occurring within the Persian period. Originally, she suggested, the wall may have been built by Zerubabel on the earlier site of Solomon’s southeast Temple podium of the Temple Mount.

However, if Zerubabel, on his return from exile, had difficulty building even a modest Temple (as the Biblical documents indicate), he could scarcely have completed a wall as impressive as this early eastern wall. At least one scholar, Dr. Ernest Marie Laperrousaz9, has suggested dating the lower courses right of the straight joint to the time of King Solomon. Laperrousaz relies on the similarity between this masonry and that of the Phoenicians. (The Bible tells us that Solomon employed Phoenician masons to construct the Temple.) If Laperrousaz is right, then the Lower Gate may be Solomonic!

In any event, the dating of the masonry right (north) of the straight joint is probably the best clue we have to dating the two or three lowest courses of the wall adjacent to the Golden Gate. And the date of these lowest courses would be the best indication of the date of the gate below the Golden Gate, for the Lower Gate appears to have been built into the courses of this earlier wall.

Perhaps the most important implication of the presence of the Lower Gate below the threshold of the Golden Gate is that this area has long been identified as a location for the eastern entrance into the Temple Mount. Many Jerusalem maps show a Temple gate due east of the Dome of the Rock in the Haram esh-Sharif. The Golden Gate, however, is located about 350 feet north of this point. We now know that the location of the present Golden Gate was determined by an earlier gate.

The precise dating of the Lower Gate must, for the present, remain problematic. Only excavation could determine the exact relationship of the Lower Gate to the lower courses exposed in the eastern wall. The very existence of the arch implies that a gateway at this elevation would have cut through at least eight to ten courses of this ancient masonry.

The best archaeological evidence for dating the Lower Gate seems to be the masonry to the right of the straight joint. Most scholars date this masonry on archaeological and historical grounds to sometime before the Herodian period. The Lower Gate would, therefore, also date to a period earlier than the Herodian. How much earlier, we cannot be sure. But a date as early as the reign of King Solomon is not impossible. It is even possible that such a gate, revered through the ages, continued to be used for a thousand years or more and was thus the gate through which Jesus entered the Holy City.

MLA Citation

Footnotes

Endnotes

See “The Rose of Jericho,” BAR 06:05.

For a thorough discussion of whether the “Beautiful Gate” of Acts 3:2, 3:10 is the eastern city gate or an interior Temple gate leading from the Court of the Gentiles on the east to the Court of Israel, see Jack Finegan, The Archaeology of the New Testament (Princeton University Press, 1969), pp. 129–130.

A report that the tomb in front of the Golden Gate was partially destroyed by a bomb in the June 1967 Israeli-Arab war can be found in a pamphlet by Eli Schiller called The Golden Gate (Ariel Publishing House, 1975 [Hebrew]), pp. 6–7.

See K. Creswell, “Early Muslim Architecture,” and Spencer Corbett, “Some Observations on the Gateways to the Herodian Temple in Jerusalem,” Palestine Exploration Quarterly (January–April 1952).

For an account of another phase of Warren’s explorations, see “Jerusalem’s Water Supply During Siege—The Rediscovery of Warren’s Shaft,” BAR 07:04.

See Yoram Tsafrir, “The Location of the Seleucid Akra in Jerusalem,” Revue Biblique, Vol. 82, p. 177.

See M. Dunand, “Byblos, Sidon, Jerusalem,” Vetus Testamentum, XVII, 1968; and Kathleen Kenyon’s works Digging Up Jerusalem (1974) and Royal Cities of the Old Testament (1971).