Looter? Treasure Hunter? Thief? Genius? Hero? Constantine Tischendorf has been called all of these. As he turns 200 and in light of recent archival discoveries, it may be time to consider whether some of these judgments are too harsh.

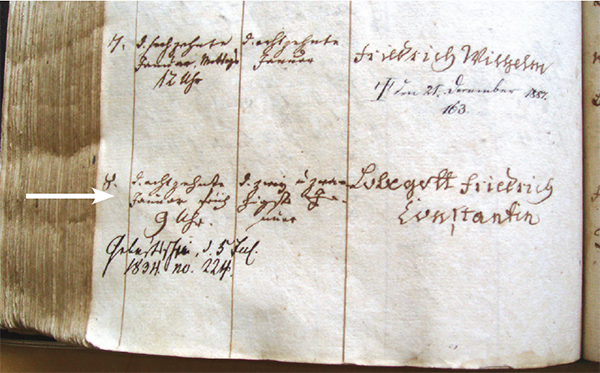

Tischendorf’s special interest was New Testament textual criticism. The son of a physician, Tischendorf was born in 1815 in Saxony and spent his scholarly career at the University of Leipzig. The highpoint of his life was the discovery of the famous Codex Sinaiticus in St. Catherine’s Monastery at the foot of Mt. Sinai (or one possible Mt. Sinai).a Even earlier he had earned a scholarly reputation by deciphering the Greek of the Codex Ephraemi Rescriptus, a fifth-century codex of the Old and New Testaments that had been dismantled, erased and overwritten (a palimpsest).1 Several scholars had attempted to decipher it and failed. Tischendorf, however, was famous for his superior eyesight, which he got, as legend has it, because his pregnant mother made a plea to God that her child not be born blind after she encountered a blind man on the street—a request that was apparently granted with exuberance.

Tischendorf’s life ambition was to discover the oldest Biblical manuscript in existence. He saw it as a holy quest. Although cynicism regarding his motives and actions plagued Tischendorf both during his life and beyond, this shadow did not daunt him. His quest took him to Paris, Britain, the Netherlands and especially the Mediterranean. It was in the deserts of Egypt, however, that he found his fame and his prize.

Tischendorf made his first trip to St. Catherine’s Monastery in 1844. While visiting with the librarian Kyrillos, Tischendorf observed a large basket full of old parchment that the monks used to fuel fires. Tischendorf peeked into the basket and recognized Biblical text. Brimming with excitement, Tischendorf immediately intervened, thereby saving the Codex Sinaiticus, the oldest manuscript of the Bible ever found. This is Tischendorf’s version of the story, and it is by far the most often recited. There have been some skeptics, such as author James Bentley who finds it too heroic to be true,2 but as I demonstrate in my own book, Constantine Tischendorf: The Life and Work of a 19th Century Bible Hunter, there is no basis for this skepticism.3

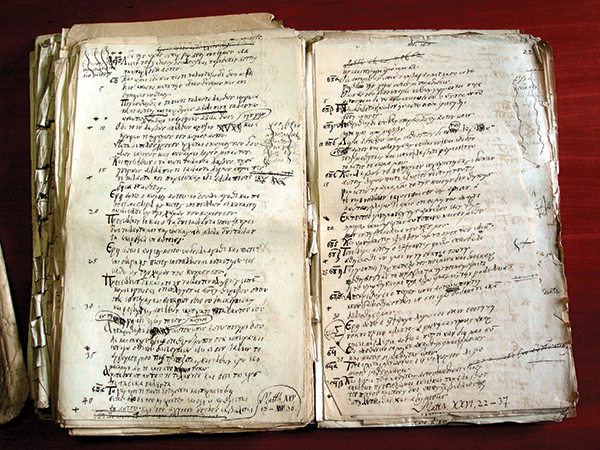

Tischendorf hoped to be allowed to take the manuscript with him. But, as he explained, “The too lively satisfaction which I had displayed, had aroused [the monks’] suspicions as to the value of this manuscript.”4 Nevertheless, Tischendorf was allowed to take 43 sheets away with him “and [he] enjoined on the monks to take religious care of all such remains.”5 He published these 43 sheets as Codex Friderico-Augustanus (named after his sponsor, King Friedrich August II of Saxony). The fourth-century manuscript was a copy of the Septuagint (LXX), an early Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible.b

Despite his success in obtaining the Codex Friderico-Augustanus, Tischendorf could not get the remaining pages out of his mind. He attempted to buy the sheets that were still in the monk’s care, but they were not interested. Soon Tischendorf was making plans to revisit the monastery in the hope of examining the rest of the manuscript and perhaps acquiring it. When he finally got there in 1853, the manuscript was nowhere to be found. He discovered only a small fragment, 11 lines from Genesis, which was being used as a bookmark. He returned to Germany virtually empty-handed.

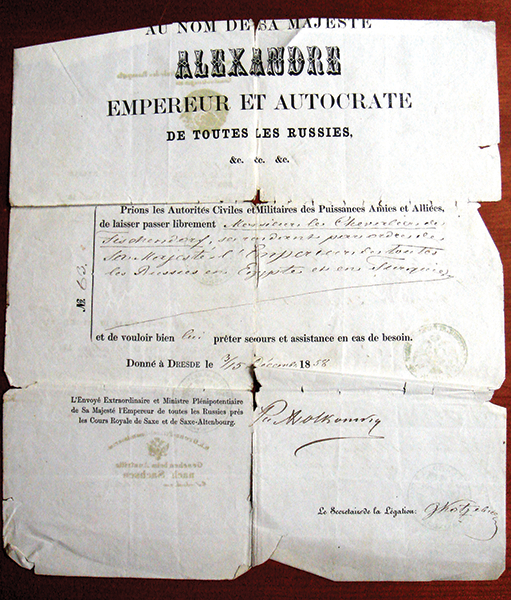

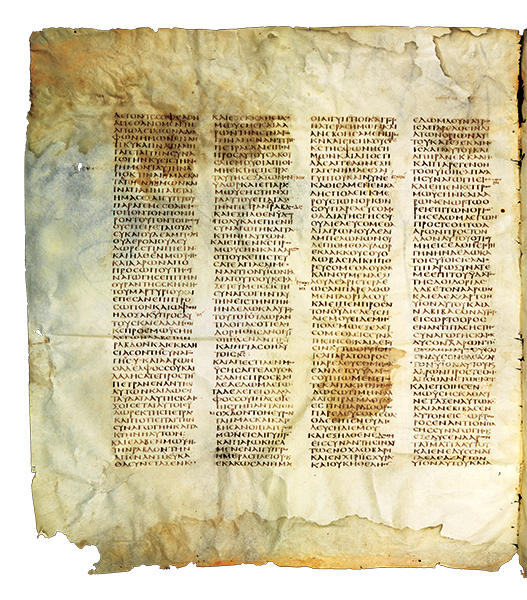

Upon hearing rumors that others had seen the remaining sheets, Tischendorf convinced the Russian Czar Alexander II to sponsor his third and final visit to the monastery in 1859. When it looked like he was going to have to leave the monastery empty-handed for a second time, things took a sudden turn. On February 4, three days before his scheduled departure, one of the monks showed him the lost manuscript, with almost twice as many pages as Tischendorf had previously seen—346 in all. The manuscript contained most of the Greek Old Testament and the entire New Testament, along with the Epistle of Barnabas and portions of the Shepherd of Hermas.c “Full of joy, which this time I had the self-command to conceal from the steward and the rest of the community, I asked, as if in a careless way, for permission to take the manuscript into my sleeping chamber to look over it more at leisure,” recalled Tischendorf. “There by myself I could give way to the transport of joy which I felt. I knew I held in my hand the most precious Biblical treasure in existence … I cannot now, I confess, recall all the emotions which I felt in that exciting moment with such a diamond in my possession.”6

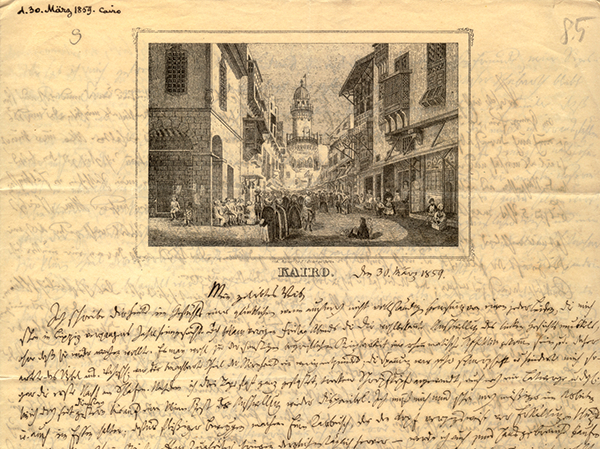

Almost immediately Tischendorf requested permission from the sacristan Skevophylax Vitalios to take the manuscript to the sister monastery in Cairo to be copied. The sacristan refused, but Tischendorf was not one to give up easily. He raced to Cairo to appeal to the abbot there. Time was of the essence, as the abbot was about to depart for Constantinople for the election of the new archbishop. The abbot gave permission for the manuscript to be brought to the monastery in Cairo, where Tischendorf was allowed to copy it with the help of two Germans who happened to be in Cairo.

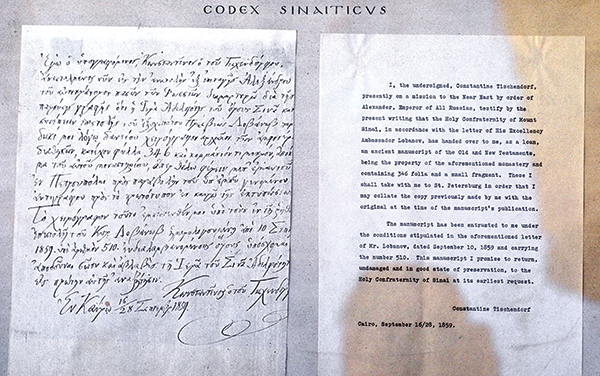

Tischendorf then suggested to the monks that the manuscript be donated to the Russian czar for safekeeping and preservation. Only the archbishop—and at the time there was none because the election in Constantinople was not going smoothly—could gift the manuscript to the czar. The favored candidate for archbishop was Cyril, but the Patriarch of Jerusalem opposed his installation. Tischendorf used the czar’s influence to get Cyril installed with the understanding that Cyril would agree to “gift” the manuscript once he was officially installed as archbishop. But after he was installed and even after being removed from office on January 21, 1867, Cyril steadfastly maintained that he had never given the manuscript away—but had only lent it to the Russians based on two letters of guarantee for its return: one on September 22, 1859, from Prince Lobanov, the Russian ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, and the other from Tischendorf dated September 28, 1859.

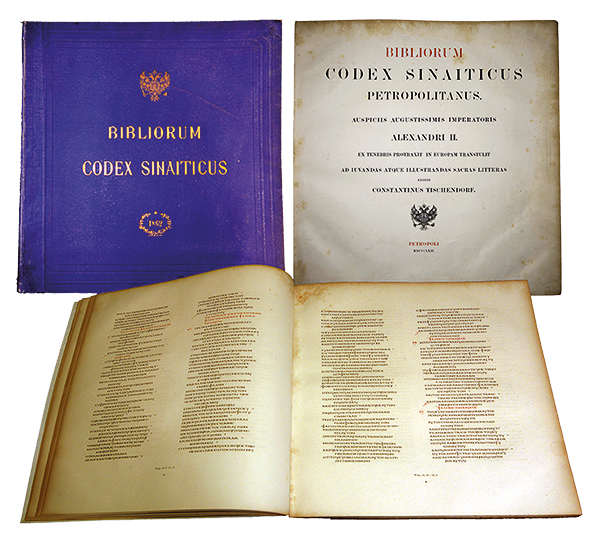

Tischendorf presented Codex Sinaiticus to the Russian royalty on November 19, 1859. Codex Sinaiticus was put on display in the Imperial Public Library. The result of this loan was that Tischendorf was able to produce a beautiful four-volume facsimile—exact reproduction copy—edition of the entire Codex Sinaiticus, which he presented to the czar in 1862. Despite how quickly he managed to produce the edition, creating the facsimile using a printing press rather than photographs was tedious work: “Tischendorf worked directly with the Leipzig printers … to create a special type that matched the manuscript as closely as possible—and three different forms of this type to match the original scribes’ hands and the varying sizes of the letters. For example, Tischendorf apparently had to design seven different sized and shaped Greek omegas (

One of the first challenges Tischendorf faced occurred when pseudo-scholar and ancient manuscript dealer Constantine Simonides claimed that he had written the codex in 1840 for his uncle to give to the czar as a present. His claim was ludicrous, but it served to increase interest in Tischendorf’s discovery. As I have said before, “Rather than the Simonides affair harming Tischendorf, it led to greater recognition of the importance of the manuscript he had discovered and published.”8 This controversy drew extra attention to the manuscript and supported its authenticity beyond reasonable doubt, especially in academic circles outside Germany.

The ten-year gap between the presentation of Codex Sinaiticus and Tischendorf’s receiving his reward (i.e., title) from the Russian government was the result of a drawn-out process of negotiating a deal between successive archbishops and the Russian government. As noted earlier, Archbishop Cyril maintained that the codex was only on loan for as long as he held the office. The Russians took Codex Sinaiticus off display and put it in storage until the issue of ownership was settled. They also engaged N.P. Ignatieff, the Russian ambassador to the Sublime Porte, to negotiate with the monks. Perhaps as a strategy to ingratiate himself to the monks and thereby convince them to sell/donate Codex Sinaiticus to the Russian government, Ignatieff had used the word “stolen” to describe the Russian possession of Codex Sinaiticus. In order for something to be stolen, there must be a thief, and in this case, that thief would have to be Tischendorf. This is a label that has stuck to the devotedly religious scholar throughout his life and legacy.

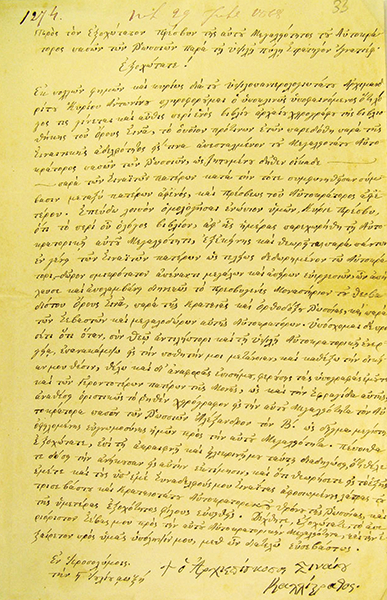

It was not until 2005 that documents from the Russian archives revealed the rest of the story and freed Tischendorf from the shackles of scholarly shame. Once again the vacuum in the archbishop’s seat presented the Russians with an opportunity. Ambassador Ignatieff approached Archbishop Cyril’s rival Kallistratus and made a deal for the most important Biblical manuscript ever discovered. Several documents, now in the Russian archives, reveal that the monks of St. Catherine’s encouraged Ignatieff to support Kallistratus for the position of archbishop, which he could obtain for him by using Russia’s influence in the Orthodox world, in exchange for giving the Codex Sinaiticus to the czar for a small sum of money—9,000 rubles—and some Imperial decorations. Kallistratus became archbishop, and the Russians became the official owners of the Codex Sinaiticus. Tischendorf was made a minor noble, and on July 15, 1869, Archbishop Kallistratus wrote Tischendorf a letter acknowledging the gift of the codex to the czar. Tischendorf died from a stroke five years later as both the most famous and most infamous textual scholar in history.

Today little dispute is left as to whether the donation was ever made by the monks of St. Catherine’s, but there is great debate as to whether it was made voluntarily. Some still regard Tischendorf as a thief in that he initially stole the Codex Sinaiticus and encouraged the Russians to force the archbishop to give in. University of Missouri-Columbia professor Joseph J. Hobbs claims that Tischendorf “wrestled” the codex away from the monks.9 And many still lament that Codex Sinaiticus never made its way back to St. Catherine’s. “These monks have been abused by western imperialism; they deserve our long overdue support and deep respect,” laments eminent Biblical scholar James H. Charlesworth.10

These claims don’t take into account, however, the common practice at the time of donating or selling ancient manuscripts. What Tischendorf did with Codex Sinaiticus was no different from what he had done with hundreds of other manuscripts, which was in line with the way in which textual scholars worked at the time and was questioned by no one. Unfortunately, due to political turmoil in the leadership of the monastery, the process with Codex Sinaiticus was prolonged for an unusual length of time, and that abnormal occurrence cast shadows onto Tischendorf’s ethics as a means of accounting for the atypical transaction.

After a detailed study of all the documents and literary remains of the transaction between the monks of St. Catherine’s and the Russian government, New Testament Professor Christfried Böttrich concluded that the transaction was completed legally and that Tischendorf should be exonerated of wrongdoing.11 Furthermore, respected scholar D.C. Parker claims that the documents demonstrate that the amount of compensation given to the monastery in exchange for Codex Sinaiticus was the heart of the dispute and not the actions of Tischendorf, who played only a minor role, in Parker’s estimation.12

No other human being has discovered and published as many Biblical manuscripts as Constantine Tischendorf. Of course he never equaled his discovery of the Sinai codex—how could he? Nevertheless, to the end of his life, he was an avid Bible hunter. When he died at the relatively young age of 59, he had changed the course of Biblical textual scholarship.13

In 1933, Russia, in financial straits, sold most of Codex Sinaiticus to the British Library. Only a few fragments remain in the Russian National Library. The first pages that Tischendorf brought out in 1844 are in the University Library of Leipzig. Twelve more leaves and some fragments were discovered in 1975 at St. Catherine’s Monastery and remain there. It seems unlikely that these various pages will ever be brought together under one roof. But a modern solution has been found that reunites all the remaining pages of the codex. In time for Tischendorf’s 200th birthday, Codex Sinaiticus has been digitized and placed in a virtual museum.

Many celebrations took place in Lengenfeld, Tischendorf’s birthplace, in honor of his 200th birthday. A large exhibit of historic manuscripts, including original Luther Bibles and an Erasmus text from 1519, was mounted by Tischendorf specialist Alexander Schick to recognize Tischendorf’s life and contribution to Biblical textual scholarship. The display also included personal items from the Tischendorf family. Special lectures were given on January 17–18, 2015. And Schick has written a book in German to commemorate the occasion.14

MLA Citation

Footnotes

Hershel Shanks, “Who Owns the Codex Sinaiticus?” BAR 33:06.

Hershel Shanks, “How the Septuagint Differs,” BAR 02:02; David Marcus and James A. Sanders, “What’s Critical About a Critical Edition of the Bible?” BAR 39:06; Emanuel Tov, “Searching for the ‘Original’ Bible,” BAR 40:04.

Carolyn Osiek, “The Shepherd of Hermas,” Bible Review 10:05.

Endnotes

While Codex Bezae is not one of the manuscripts that Tischendorf edited, there is a legend that I note in my recent book that he was involved with this important codex as well. The Codex Bezae was kept in the Library at Cambridge, and sometime near the end of the 19th century it was noted that the leaves at the end of the codex were absent. When they investigated who had last used the codex, they found it was Tischendorf. After writing to Leipzig about the missing pages, the library received them through the mail with a note explaining that Tischendorf was not able to finish with them before leaving Cambridge, so he took them with him in order to complete his research. It is an interesting legend, but there is no paperwork to support this story. See Stanley E. Porter, Constantine Tischendorf: The Life and Work of a 19th Century Bible Hunter, Including Constantine Tischendorf’s When Were Our Gospels Written? (London: Bloomsbury, 2015), pp. 62–63.

Constantine Tischendorf, Codex Sinaiticus (London: Lutterworth Press, 1934), p. 24; Porter, Constantine Tischendorf, p. 124.

James H. Charlesworth, “Foreword,” Secrets of Mount Sinai (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1986), p. 5.

Christfried Böttrich, “Constantin von Tischendorf und der Transfer des Codex Sinaiticus nach St. Petersburg,” in Andreas Gössner, ed., Die Theologische Fakultāt der Universitāt Leipzig (Leipzig: Evangelische Verlagsanstalt, 2005), pp. 270–274. See also Christfried Böttrich, Der Jahrhundertfund: Entdeckung und Geschichte des Codex Sinaiticus (Leipzig: Evangelische Verlagsanstalt, 2012).

D.C. Parker, Codex Sinaiticus: The Story of the World’s Oldest Bible (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 2010), pp. 143–147.